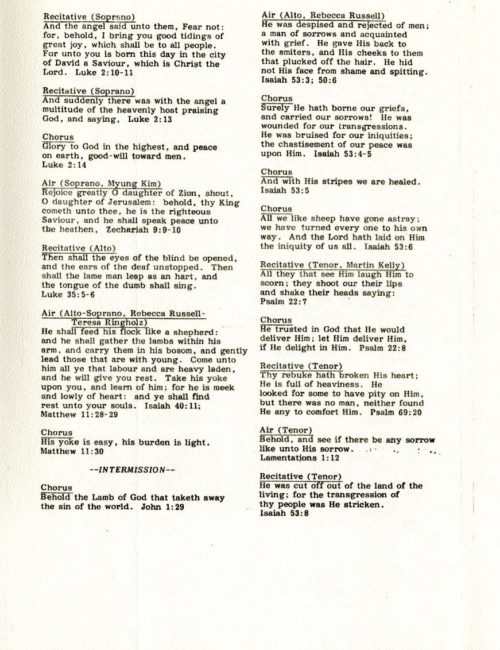

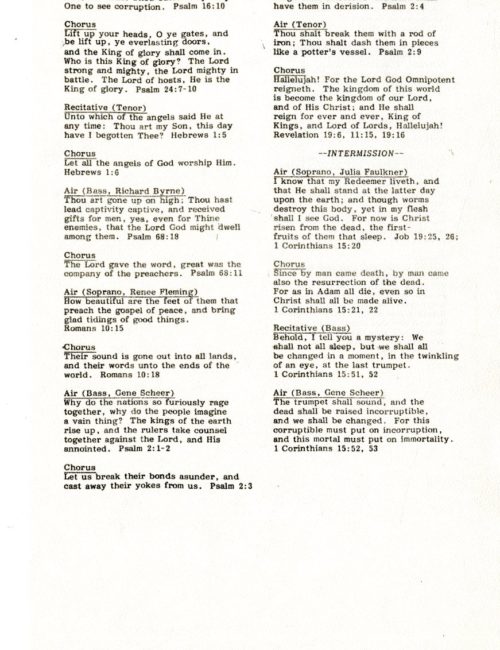

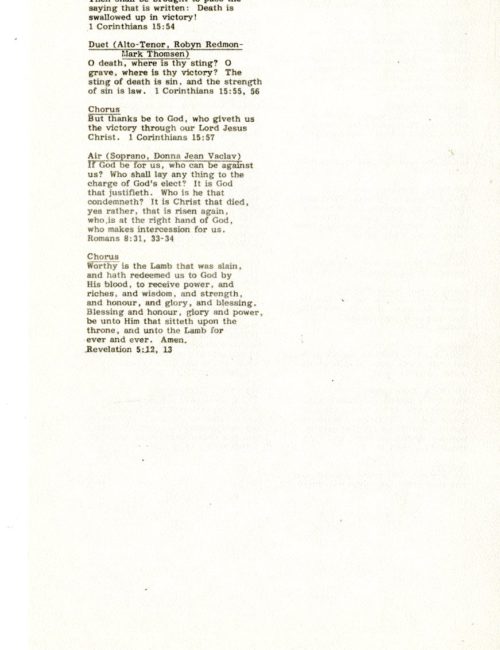

Dec 5th – 11th: Performances of George Frederic Handel’s Messiah

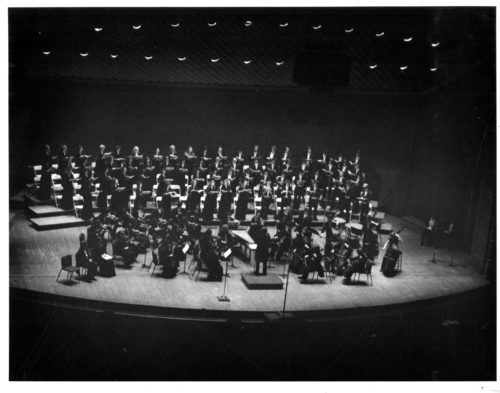

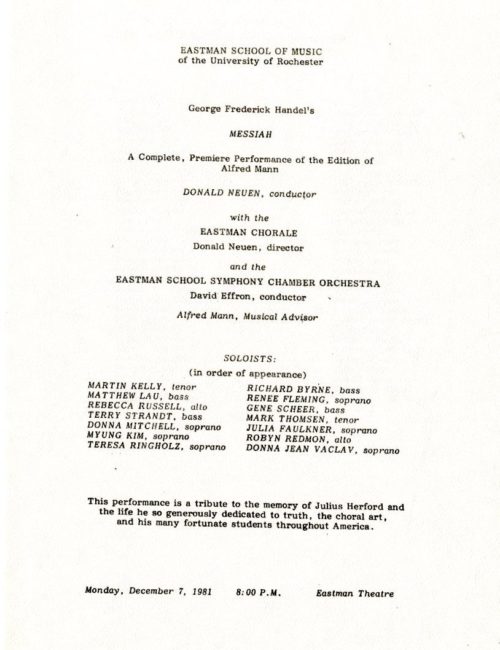

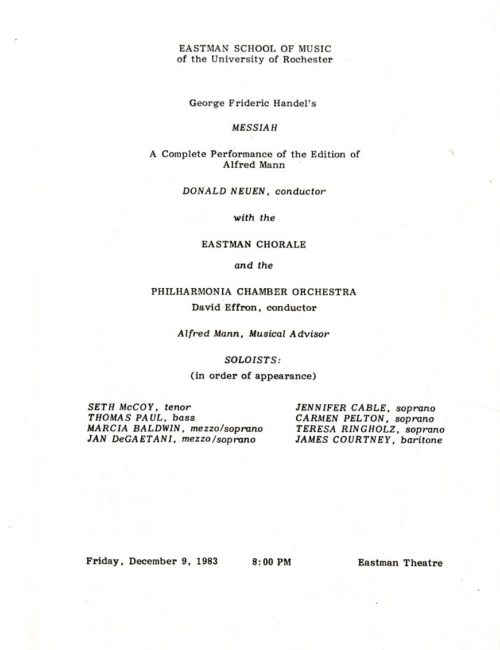

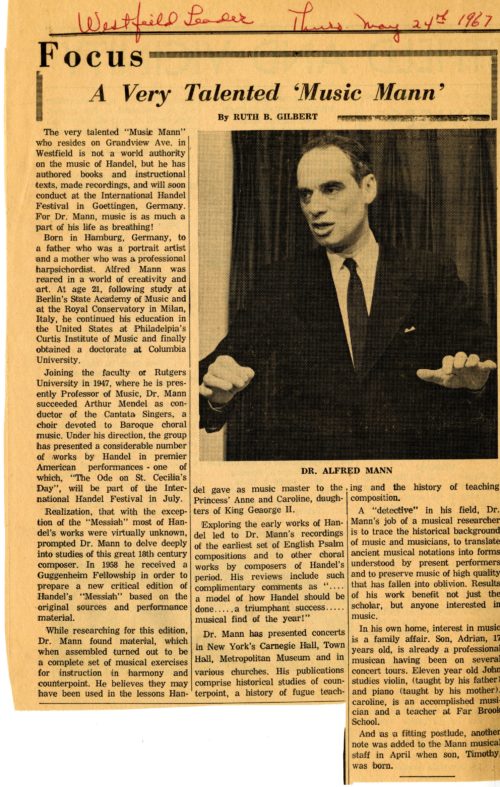

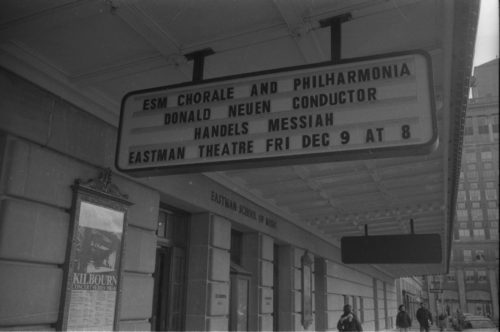

December 5, 2022Throughout the Western world, and particularly in English-speaking countries, December is always a time of performances of George Frederic Handel’s beloved oratorio Messiah. Whether in professional venues, in houses of Christian worship, or at academic institutions; whether in full or in part (given the customary Christmas-season practice to restrict performance to the oratorio’s first part); and whether live or transmitted over mass media, this music is not far from reach. Here at the Eastman School of Music, however, Messiah has only seldom been performed. In 1942, to mark the 200th anniversary of Messiah’s premiere performance, Eastman forces gave two performances of parts II and III (on May 17-18, 1942), and then a performance of part I (on December 15, 1942), all conducted by Herman Genhart.[1] Three decades later, parts II and III were performed on April 27th, 1973, conducted by Robert De Cormier.[2] Messiah was eventually heard at Eastman in its entirety in the early 1980s, 39 and 41 years ago this week, when on the evenings of Friday, December 7th, 1981 and Friday, December 9th, 1983, the Eastman Chorale performed the oratorio under conductor Donald Neuen,[3] joined in each performance by chamber orchestra and soloists. The two performances marked a departure in that they were based on a new edition by renowned musicologist Alfred Mann.[4] Significantly, the 1981 performance marked the premiere of Mann’s edition, and the 1983 performance was accompanied by the release of a commercial recording. Dr. Mann, an Eastman School faculty member at the time, served as Musical Advisor to both Eastman Chorale performances and also the Eastman School’s commercial recording project.

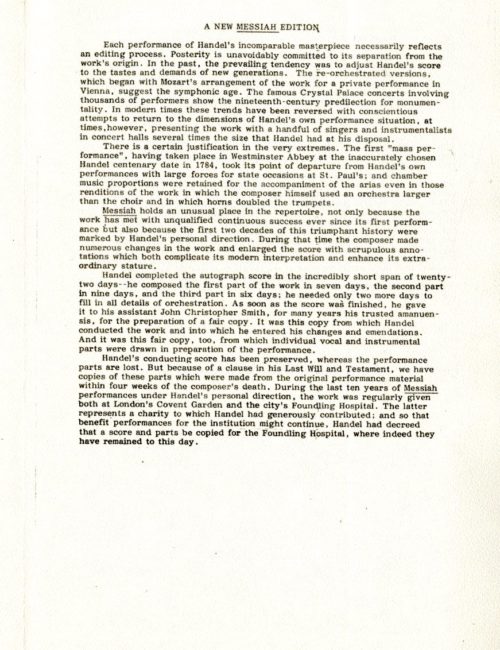

Messiah occupies a unique place in the choral literature, for as Dr. Mann pointed out, it “. . . remains the only work of its time that has seen a continuous sequence of revivals, for almost two decades under the direction of the composer, for two further decades under conductors who had shared in Handel’s work on the London scene, and for the two following centuries through the devotion of generation after generation. The legacy upon which the interpreter of this work enters is of unique complexity.”[5] The implications are tremendous: a work more o rless continuously in the repertory since the composer’s own lifetime, but having varied markedly in its interpretation down through the years. Famously, the performance legacy around Messiah has run the gamut in all respects, and the chamber-sized performing forces of the composer’s day gave way to the larger forces (“monumental” is the adjective used by numerous writers) of the 19th-century (which spilled over well into the 20th century), and finally a 20th-century re-evaluation based on scholarly inquiry that prompted a return (in some quarters) to chamber forces. Alfred Mann, a noted choral conductor in his own right, made a priority of Handel’s music among his own research and performance interests. Working in the 1950s, he prepared a new edition of Messiah based on consideration of Handel’s conducting score and other primary sources. His edition was published in full score by Rutgers University Press (c1959-1965) in the series Documents of the Musical Past, of which Dr. Mann was editor. Each of the oratorio’s three parts was published with critical notes itemizing the manuscript and printed sources that had informed Mann’s work, and comparing the primary and secondary sources with extant modern copies. Note that the first part of his edition was published in 1959, the bicentennial of Handel’s death. Later on, the publication of instrumental parts corresponding to Mann’s edition was undertaken in anticipation of the Handel tercentenary in 1985. The full score of Mann’s edition was later reprinted in 1989 by Dover. Within that thirty-year span there was a marked increase in Handel research, including the 1957 publication of a landmark work on Messiah by Danish musicologist Jens Peter Larsen (1902-1988), who would later come to Eastman as a visiting faculty member in 1974 and again in 1983.

Mann consulted several primary sources in the service of his edition: (a) Handel’s autograph manuscript, now preserved in the British Library; (b) Handel’s own conducting score, which had been copied from the autograph manuscript by Handel’s assistant and copyist, John Christopher Smith, and is now preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford; (c) a conducting score written out by copyist Smith for his son, John Christopher Smith the younger (1712-1795), who served as organist in Handel’s performances and later directed the London Messiah performances after Handel’s death, now preserved in the Hamburg State Library; and (d) a score and complete set of parts, copied from Handel’s own performance material by several copyists under the direction of John Christopher Smith the elder, and presented by direction of Handel’s will to the Foundling Hospital (London), now preserved in the archives of the Thomas Coram Foundation. The rest of Mann’s sources were all printed editions and published critical commentaries. Significantly, Handel’s conducting score differs from the autograph in that it bears layers of annotations and additions, added by Handel in the course of directing performances of Messiah between 1742 and 1759. It was that same performance involvement to which Alfred Mann alluded when he said, “Each performance of Handel’s incomparable masterpiece necessarily reflects an editing process.”[6] As Mann also observed, “Messiah holds an unusual place in the repertoire, not only because the work has met with unqualified success ever since its first performance but also because the first two decades of this triumphant history were marked by Handel’s personal direction. During that time the composer made numerous changes in the work and enlarged the score with scrupulous annotations which both complicate its modern interpretation and enhance its extraordinary stature.”[7]

George Frederic Handel’s association with the Foundling Hospital in London is the story of a charitable impulse realized in music. The Foundling Hospital, founded in 1739 by Captain (retired) Thomas Coram (1668-1751) and established by royal charter signed by King George II, was formally promoted as the Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. As a private charity, the Foundling Hospital was from its outset entirely dependent on individual contributions; however, it soon became a much-recognized charity that would number several prominent citizens among its supporters, including artist William Hogarth (1697-1764), who was one of the Hospital’s founding governors.[8] In 1749 Handel conducted a benefit concert at the Hospital to raise funds for the completion of its chapel; the following year he provided an organ for the newly finished chapel, and conducted Messiah there on May 1st, 1750 as the new organ’s inaugural concert. In response to Handel’s generosity, the Hospital’s General Committee elected him one of the Hospital’s governors. The concert in May, 1750 was hugely successful in both musical and fundraising terms; it would prove to be merely the first in a series of annual Messiah performances at the Foundling Hospital led by Handel for the express purpose of raising funds for the Hospital’s work. Between 1750 and 1754 Handel personally conducted those performances, and after that time, with his health in decline, he continued to support the performances by his attendance up until his death. A codicil to his will directed that a copy of the score and parts of Messiah be given to the Foundling Hospital, his intention having been to provide for the continuation of the Messiah benefit performances. Those performances would, in fact, continue for another two decades. Altogether, the Messiah performances at the Foundling Hospital raised some 7,000 pounds[9] for the Hospital’s operating costs; further, where Handel’s legacy was concerned, the concerts also served to popularize the oratorio with English audiences, a point on which many writers have elaborated.

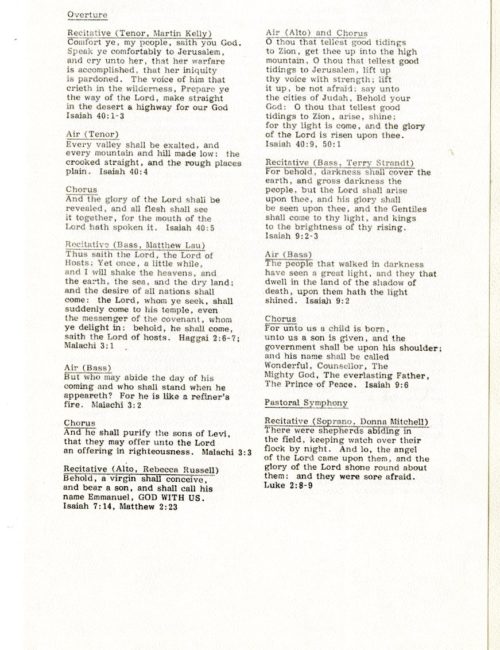

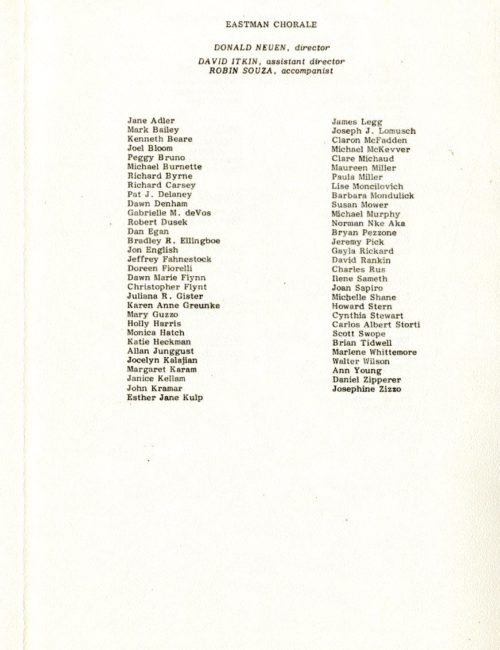

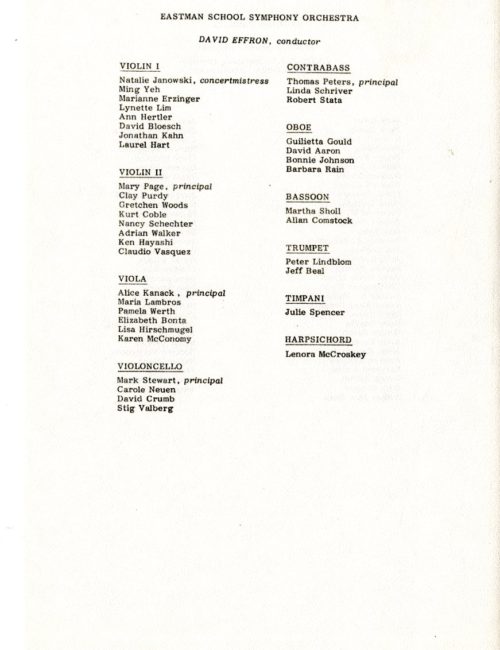

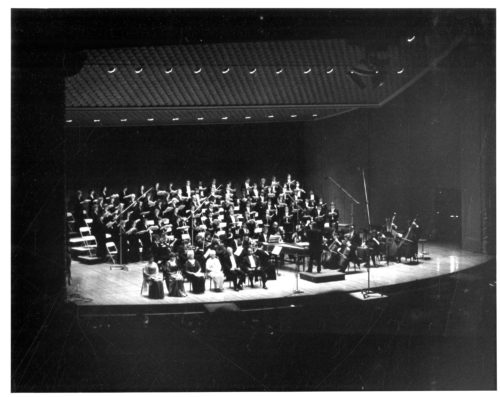

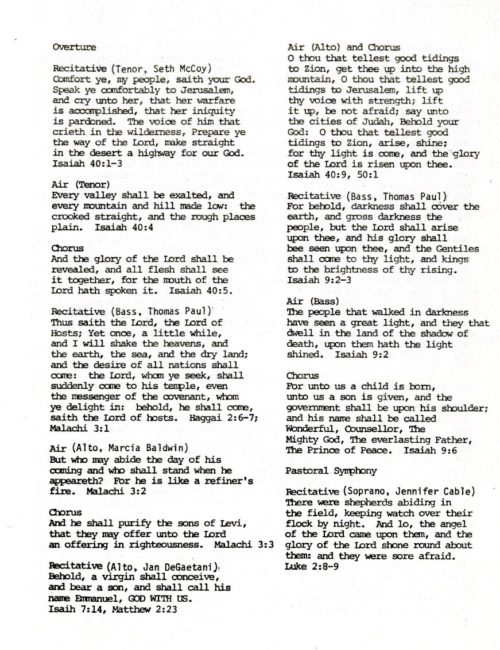

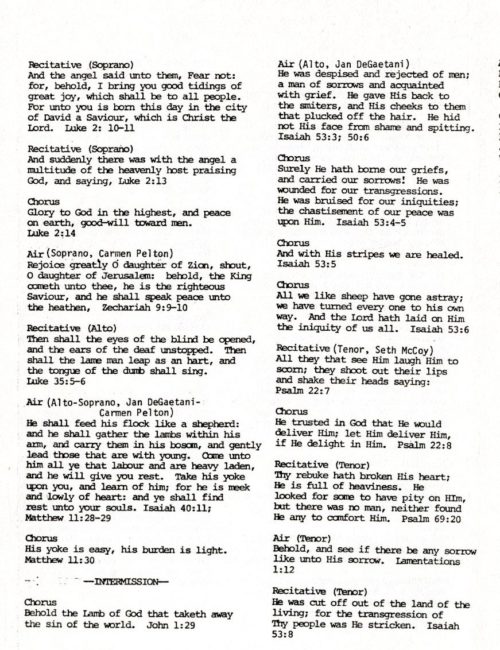

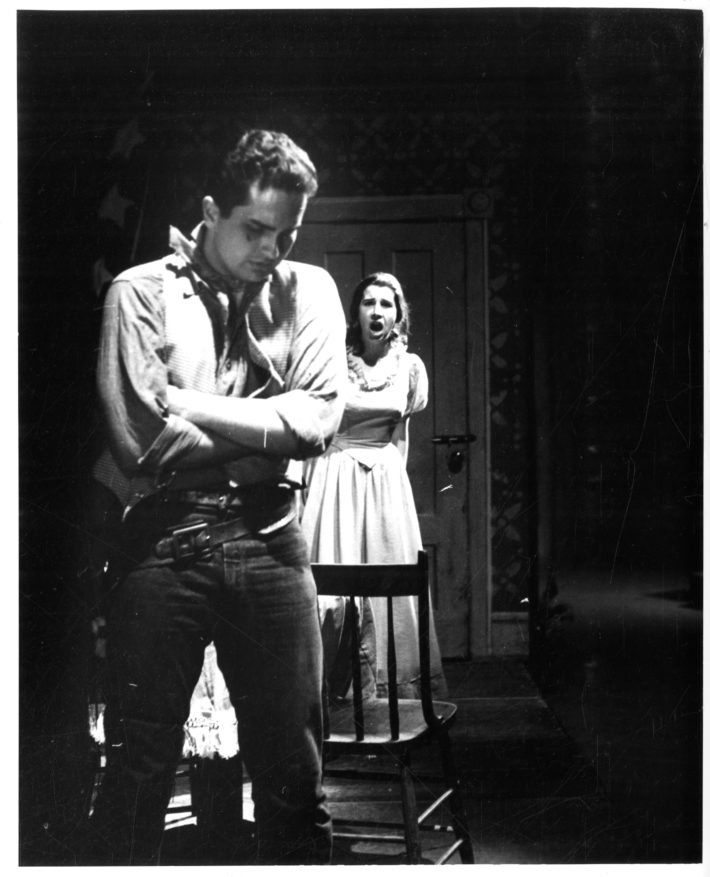

The 1981 Eastman Chorale performance featured fourteen soloists, all of whom were students; in order of appearance, they were Martin Kelly, tenor; Matthew Lau, bass (MM 1983); Rebecca Russell, alto (BM 1983); Terry Strandt, bass (DMA 1982); Donna Mitchell, soprano (BM 1983, MM 1985); Myung Kim, soprano (BM 1980, MM 1982); Teresa Ringholz, soprano (BM 1981, MM 1983); Richard Byrne, bass (BM 1985); Renee Fleming, soprano (MM 1983); Gene Scheer, bass (BM 1981, MM 1982); Mark Thomsen, tenor (MM); Julia Faulkner, soprano; Robyn Redon, alto; and, Donna Jean Vaclav, soprano (MM 1983). Mann’s edition was being heard for the first time, and taking his edition into consideration, some of the more obvious points of departure were the following.[10] In Handel’s conducting score, a division of the orchestra was apparent such that a smaller instrumental group (indicated in Mann’s score as senza rip. [ripieno]) accompanied the arias and recitatives, while the full ensemble (indicated by the rubric con rip. [ripieno]) accompanied the choruses (although even in the choruses, Handel sometimes used the smaller group). Mann also restored an 11-bar version of the “Pastoral Symphony” (at the beginning of part II), much shorter than what modern audiences have been accustomed to hearing, but something that Handel had initially intended (Handel himself had at one point crossed out the longer version). Further, Mann endorsed terrace dynamics in performance, eliminating altogether any crescendo between forte and piano. As he himself put it at this time, “What has been taken out . . . is [sic] all the influences of romantic and symphonic conceptions. Everything becomes very clear cut, black and white.”[11] Conductor Donald Neuen, for his part, described as his goal “ . . . trying to let the Messiah be a real piece of Baroque music, one that will live and dance just as it lived and danced . . . in the time that it was performed . . . and not destroyed by an overweight, pompous approach.”[12] To that end, he had assembled a chamber-sized orchestra of 29 players, selected from the Eastman School Symphony Chamber Orchestra (David Effron, conductor). He favored more lively tempos and sought to delineate shorter phrases; he also took care to segue the arias and choruses with minimum pause so as to achieve a continuous stream of music, thereby emphasizing the oratorio’s overall structure. The orchestral players were performing from parts that had been prepared and edited from microfilms of the parts that the composer had bequeathed to the Foundling Hospital. Alfred Mann was quoted as having observed, “The students’ eyes have been lighting up in rehearsals. They release that these notes haven’t been played the way Handel wanted since musicians played under Handel himself. I feel like an archaeologist.”[13] The Eastman School of Music provided a grant for the preparation of the orchestral parts corresponding to Mann’s edition, and by the time of the 1983 Eastman Chorale performance and recording, the parts had been engraved and printed. As in the full score edited by Mann, “forte” and “piano” are spelled out in full, just as they were in Handel’s conducting score and in the manuscript bequeathed to the Foundling Hospital. Throughout the parts, the rubrics “senza rip.” or “con rip.” direct when added parts are to join or else leave the ensemble.

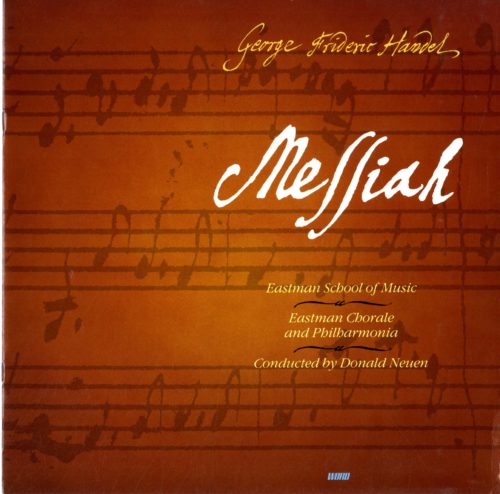

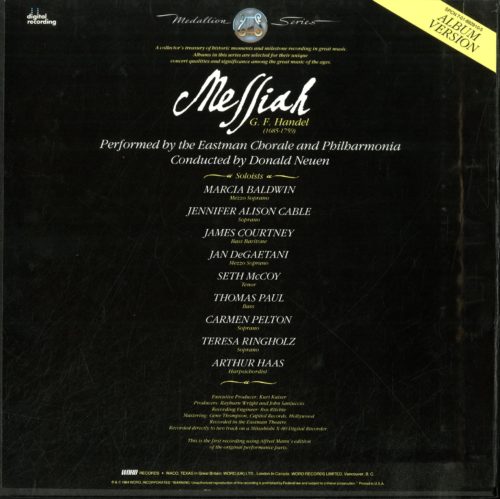

► Front and back of the commercial release of the Eastman forces’ Messiah, issued on the Word label. The boxed 3-disc set included extensive notes by Alfred Mann.

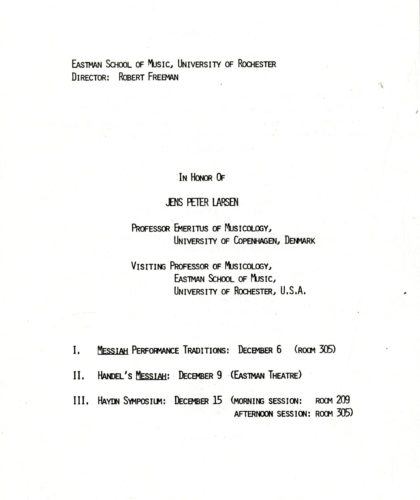

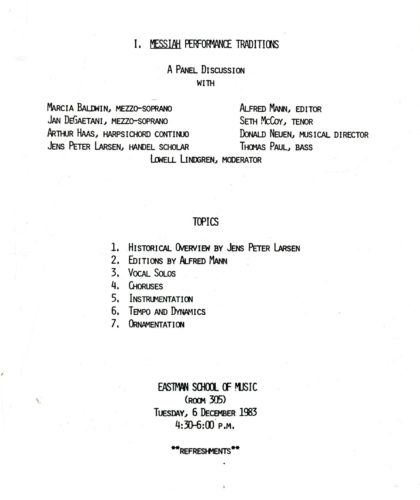

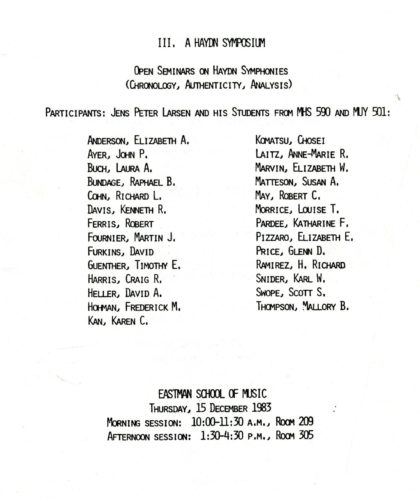

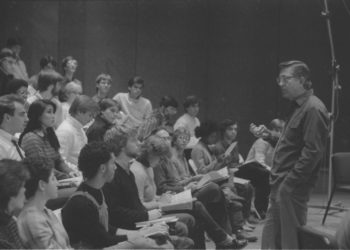

►Recognition of Professor Jens Peter Larsen during his fall, 1983 Visiting Professorship at the Eastman School including the public events promoted in this program. The panel discussion that preceded the December 9th, 1983 Messiah performance gave significant local exposure to the historical project manifest in both performance and commercial recording. Jürgen Thym Collection.

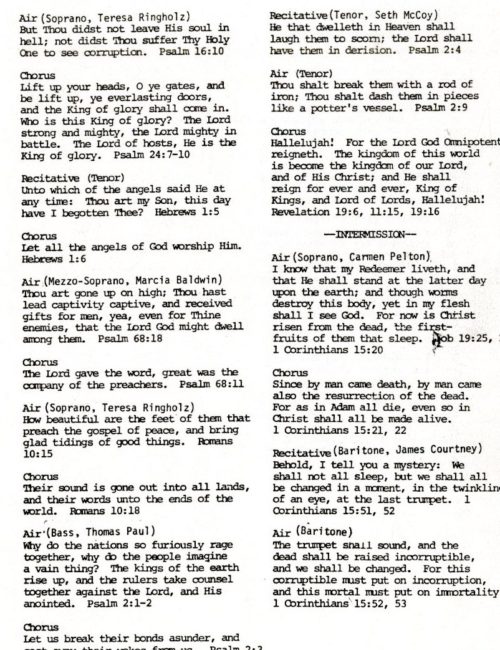

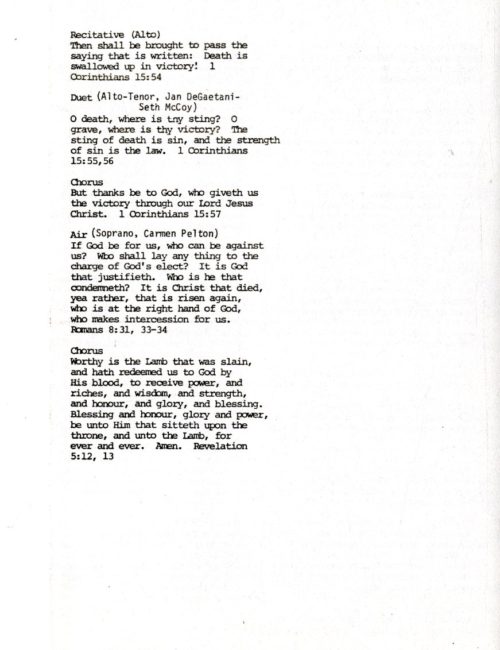

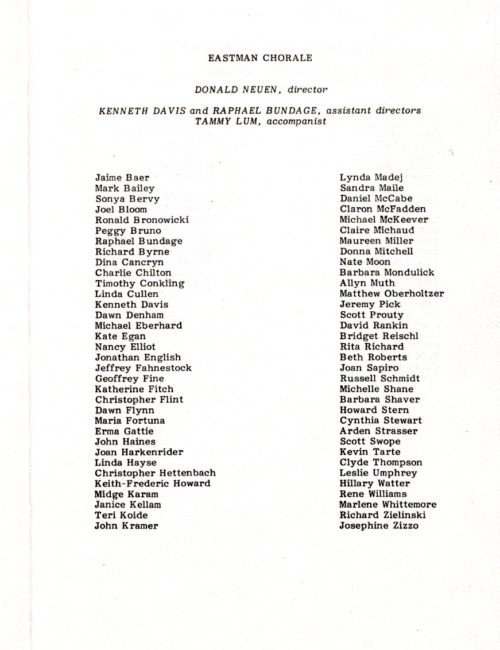

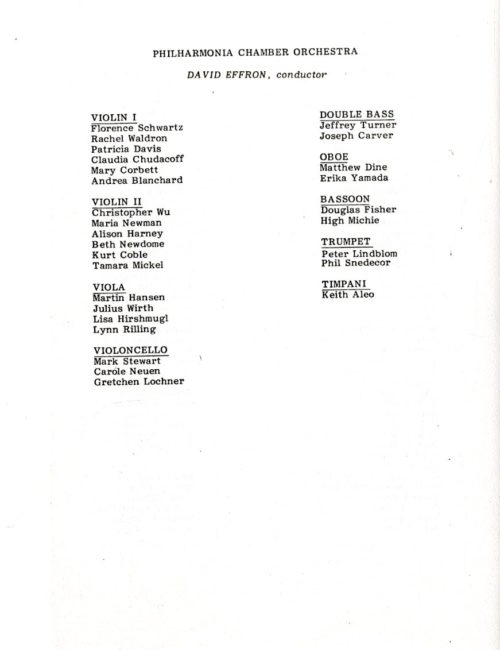

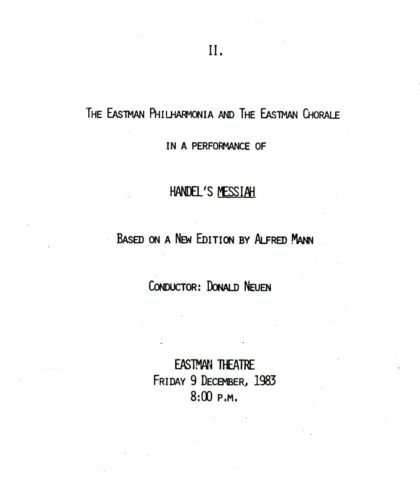

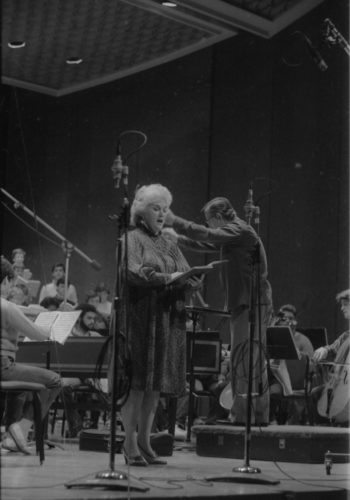

The Eastman Chorale’s 1983 performance of Messiah enjoyed the presence of another renowned Handel scholar, Danish musicologist (and Professor Emeritus at the University of Copenhagen) Jens Peter Larsen, whose work had greatly influenced modern Handel scholarship.[14] Professor Larsen was a Visiting Professor at Eastman in the fall of 1983, and on December 6th, 1983, three days before the Messiah performance, he joined a panel discussion on Messiah performance traditions alongside conductor Donald Neuen, Alfred Mann, and five of the performers appearing in the Eastman Chorale performance (four vocal soloists and harpsichordist Arthur Haas). The discussion was moderated by Lowell Lindgren. Speaking in his capacity as Handel scholar, Professor Larsen presented an historical overview, after which Dr. Mann spoke on the various editions of Messiah; the panel then discussed such topics as vocal solos, choruses, instrumentation, tempo and dynamics, and ornamentation. Three days later, on December 9th, the members of the Eastman Chorale were joined in concert by the Eastman Philharmonia Chamber Orchestra (David Effron, conductor) and eight vocal soloists, four of whom were faculty members, to perform Messiah in its entirety. The soloists were Seth McCoy, tenor;[15] Tom Paul, bass;[16] Marcia Baldwin, mezzo soprano;[17] Jan DeGaetani, mezzo soprano;[18] Jennifer Cable, soprano (MM 1983, DMA 1989); Carmen Pelton, soprano (MM, PC 1980); Teresa Ringholz, soprano (BM 1981, MM 1983); and, James Courtney, baritone (MM 1973).

On the following day, Saturday, December 10th, those same forces gathered in the Eastman Theater for a recording session, the result of which was a commercial release of Messiah on the Word Records label (p1984). This recording constituted the premiere recording of Alfred Mann’s edition, and it also represented one of the Eastman School’s contributions to the Handel Tercentenary in 1985. Copies of this 3-LP set are available in the Sibley Music Library. Word Records also released a CD recording of excerpts, Choruses from The Messiah (p1985). For audiophiles, I should mention that the LP release of Messiah was accompanied by a release on audio-cassette (a 3-cassette set, a copy of which is in the Sibley Music Library). To date the Eastman Chorale’s Messiah has not been re-issued digitally in its entirety, but a selection of ten excerpts (ending with the “Hallelujah” Chorus) was released on the CD set The Spirit of Christmas: Highlights from Messiah / Nutcracker (Vox Music Group 7215) (p2000). That issue is now streamed in the Naxos Music Library.

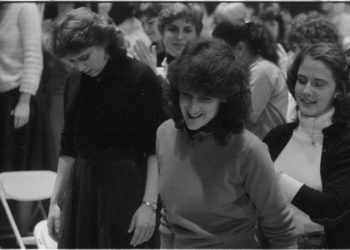

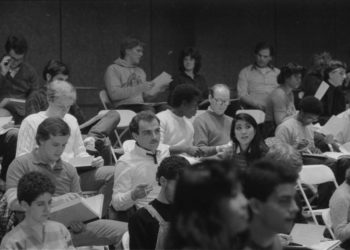

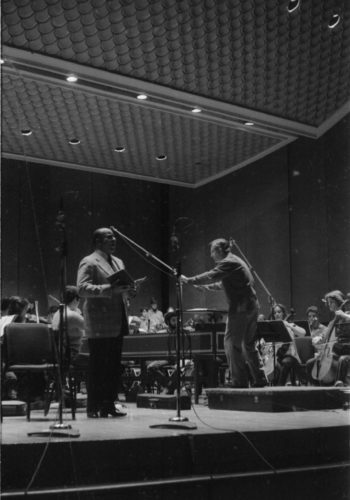

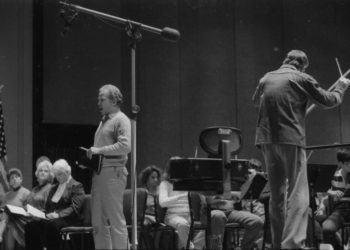

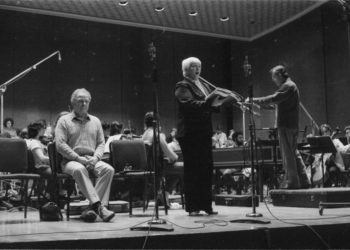

►On the day of the recording session, December 10th, 1983, members of the chorus and the vocal soloists all participate in preliminaries.

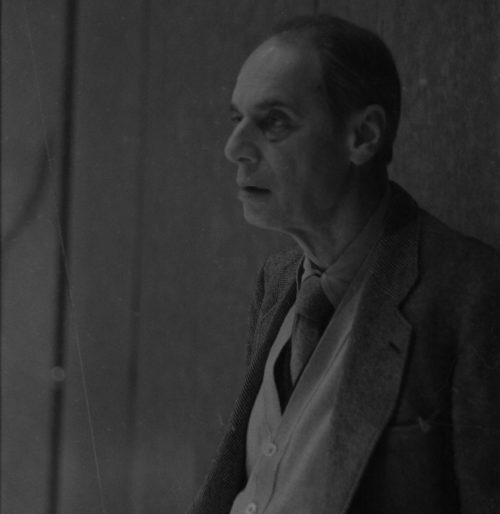

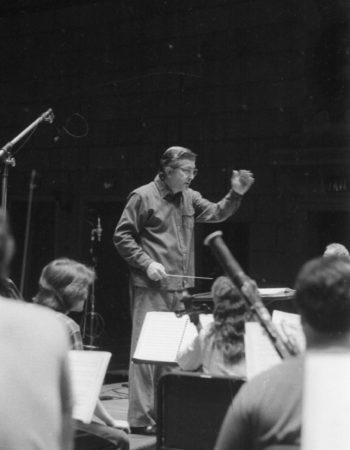

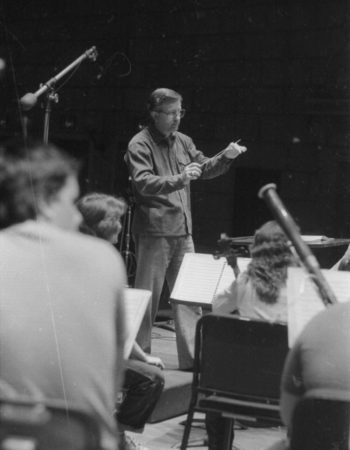

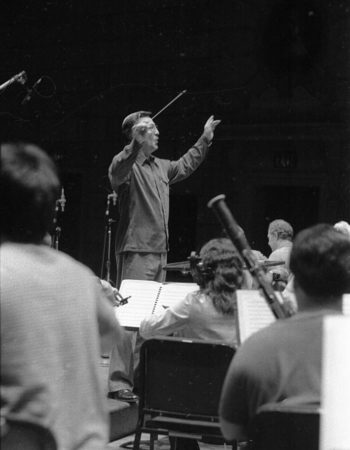

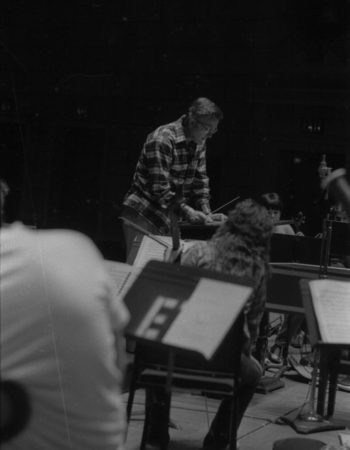

►Conductor Donald Neuen on the day of the Messiah recording session, December 10th, 1983.

►Various shots of the vocal soloists for the Eastman Chorale’s 1983 performance of Messiah.

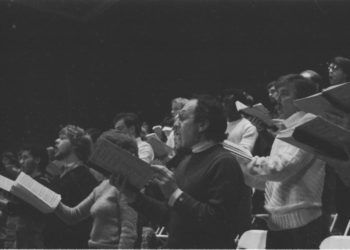

►Members of the Eastman Chorale on the day of the Messiah recording session, December 10th, 1983.

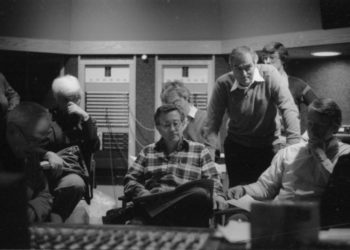

►Principals gather in the control room to hear playbacks. Variously seen in these shots are conductor Donald Neuen, producer Ray Wright, recording engineer Ros Ritchie, harpsichordist Arthur Haas, and several of the vocal soloists.

All of the Eastman School performances cited in this entry (1942, 1973, 1981, 1983) were recorded by Eastman School personnel. The masters reside in the Eastman Audio Archive.

_____________________________________________________________________________

[1] Faculty member; served from 1925 until his retirement in 1964.

[2] Faculty member; served 1972-1976.

[3] Faculty member; served 1981-1993.

[4] Faculty member. Dr. Mann (1917-2006) served at Eastman 1980-1987 following his retirement from Rutgers University.

[5] “The work and its performance” by Alfred Mann. Notes accompanying the commercial LP release Messiah, WORD Records SPCN 7-01-892910-5.

[6] “A new Messiah edition” by Alfred Mann. Handel and Haydn Magazine, vol. II, no. 1 (fall 1982). Pages in the issue are unnumbered.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The charitable interest taken by William Hogarth and several of his fellow artists in the mission of the Foundling Hospital is promoted on several websites, including those of the Foundling Museum (URL: https://foundlingmuseum.org.uk/our-art-and-objects/foundling-collections/hogarth-and-company/ ) and HENI Talks (URL: https://henitalks.com/talks/william-hogarth-foundling-hospital/ ), both accessed on December 14, 2022. Significantly, an exhibition of paintings set up by Hogarth at the Foundling Hospital has been recognized as having likely been the first public art exhibition anywhere in England.

[9] “The London Foundling Hospital by Joseph Dyer. Handel & Haydn Magazine, volume II, no. 1 (Fall 1982). Pages unnumbered.

[10] These and other performance aspects were recounted by Mann in “A new Messiah,” Eastman Notes, volume 15, no. 2 (March 1982), pages 2-3. Further aspects were noted in the two press items cited immediately following.

[11] “The Messiah: A new interpretation” by Dave Stearns. Rochester Times-Union, December 4, 1981.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Old World touch of Alfred Mann reshapes Handel” by Stephen Wigler. Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, December 7, 1981.

[14] Of particular importance in this regard was his monograph Handel’s Messiah: Origins, Compositions, Sources (W. W. Norton, 1957)A second edition appeared in 1972 and a further new edition in 1989. Alfred Mann provided a tribute to Jens Peter Larsen for the book’s second edition. The book’s introduction (translated into English by Alfred Mann) posed, perhaps somewhat provocatively, the leading question “Is there a definitive version of Messiah?” and is well worth reading on its own.

[15] Faculty member. Mr. McCoy (1928-1997) served from 1982 until he took leave due to ill health.

[16] Faculty member. Mr. Paul served as a visiting faculty member in 1972-73, and then permanently on the faculty from 1973 until his retirement in 2000.

[17] Faculty member. Ms. Baldwin (1936-2016) served from 1981 until her retirement in 1995.

[18] Faculty member. Ms. DeGaetani (1933-1989) served from 1973 until her death in 1989.