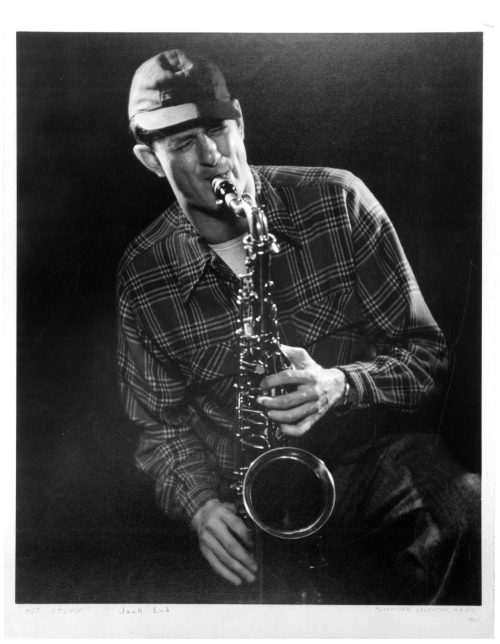

April 11th-17th: Jack End@Festival of American Music & EJE

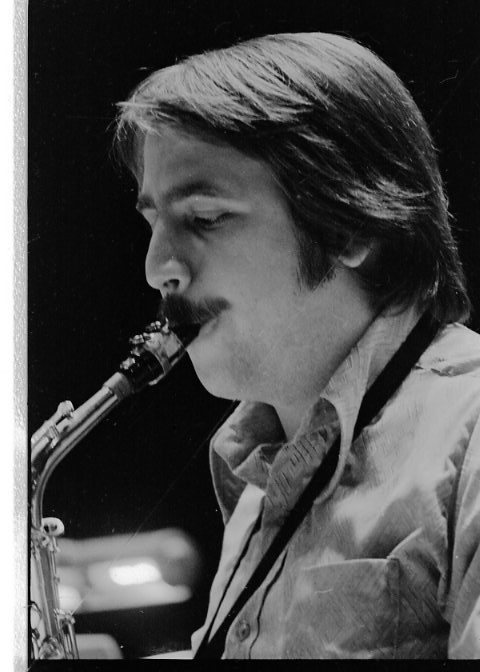

April 11, 20221946: Jack End and his ensemble at the Festival of American Music

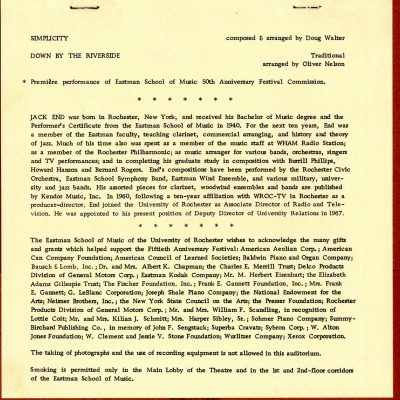

Back in November (week of 22nd-28th) I had occasion to write about Jack End, BM ’40, a sometime Eastman School faculty member (served 1940-50) and University of Rochester administrative professional who in 1967 was named Director of the newly founded Eastman Jazz Ensemble. This week, by happy coincidence of the calendar, I have occasion to write about Mr. End in connection with two milestones. The late Frederick Fennell, BM ’37, MM ’39, who knew Jack End when both were undergraduates (Fennell was a senior in 1936-37 when End was a freshman and a member of Fennell’s symphony band), once wrote of Mr. End, “Jack End was a rare man who had the patience and curiosity to follow his talents to the directions in which they led him.”[1] Even when music was no longer the focus of his day job, he was closely involved with music and with musicians in several capacities—as a “club-date musician” (in Fennell’s words), as an arranger, and as a director. Further, Mr. End was one of Rochester’s own: born here, educated here, employed here (working for one division or another of the University of Rochester for all but ten of his 35 years’ professional employment), and stayed here in his retirement. An interesting man, this Jack End, and someone deserving of our continuing respect.

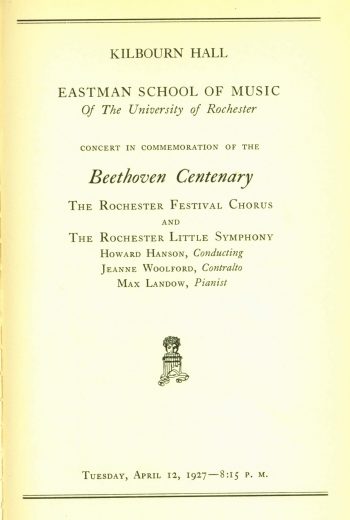

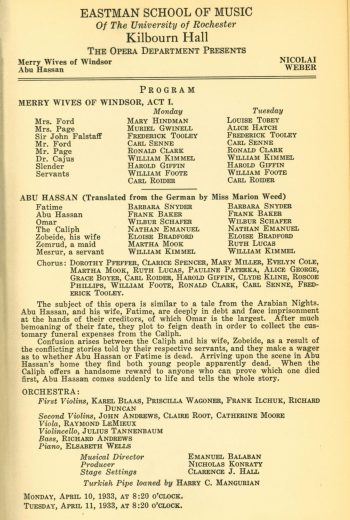

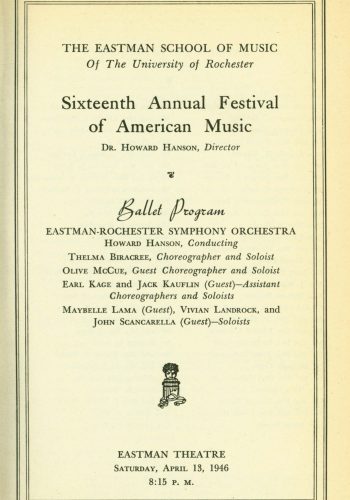

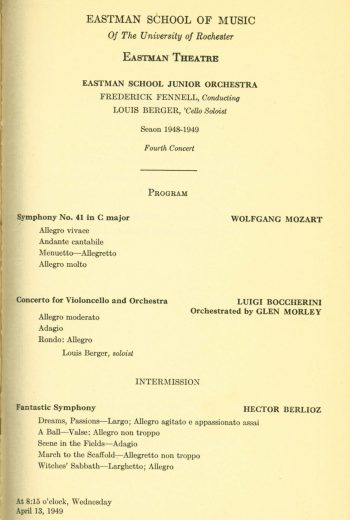

Seventy-six years ago this week, on Tuesday, April 16th, 1946, a young (28yo) faculty member and his student ensemble were invited to the stage at that year’s Festival of American Music. I can argue with conviction that their performance—formally promoted in the concert program as a “Program of Concert Music in the Jazz Idiom”—was the first public performance of jazz at the Eastman School of Music. My study of Eastman School concert programs has not turned up any previous event that can compete for this distinction. Thirteen years in advance of the first Arrangers’ Institute and Arrangers’ Holiday (in 1959), and twenty-one years in advance of the founding of the Eastman Jazz Ensemble (in 1967), faculty member Jack End and his students performed before a standing-room-only crowd in Kilbourn Hall, and in so doing, chalked one up for the list of Eastman School milestones.

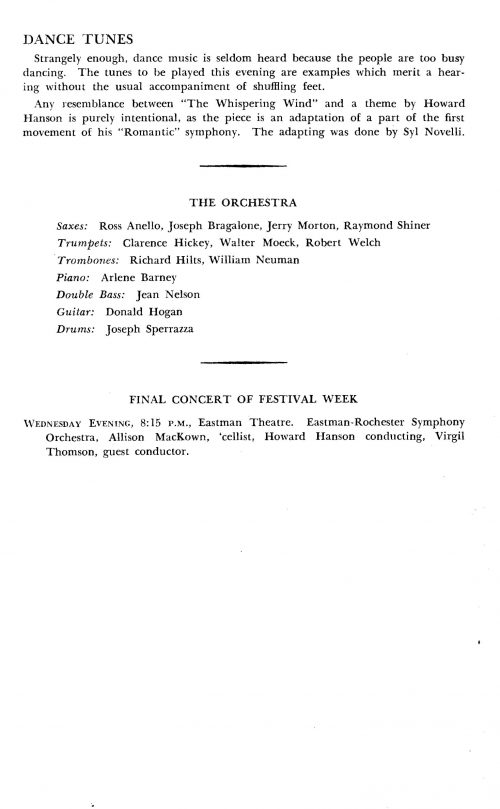

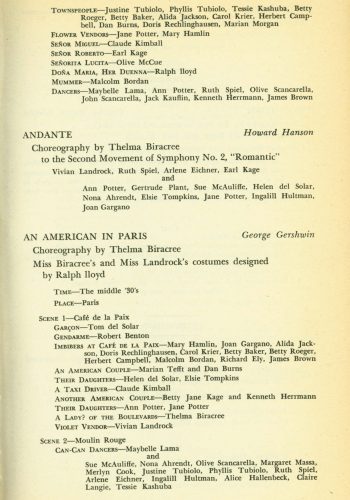

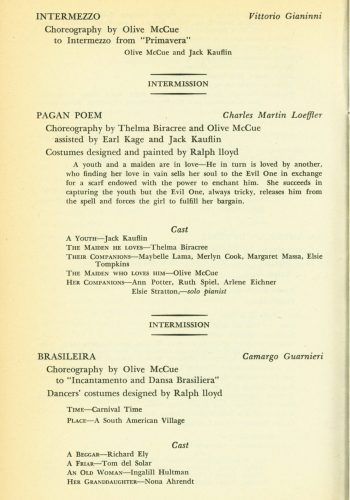

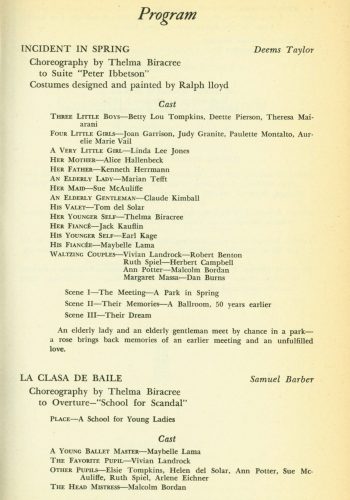

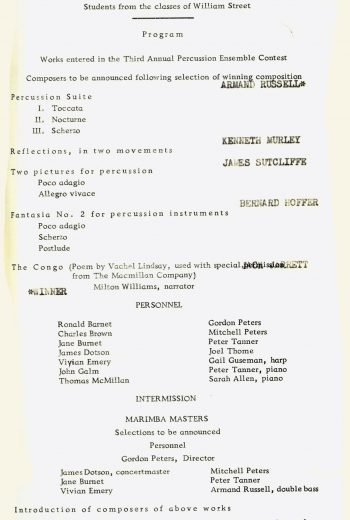

Printed program of the jazz concert at the 1946 Festival of American Music. An earlier concert at the Festival had featured Jack End’s suite Floor Show, a work less obviously in the jazz idiom.

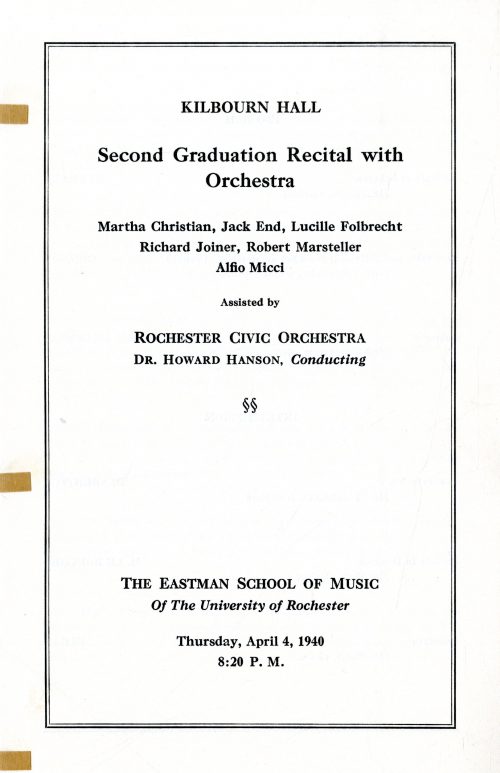

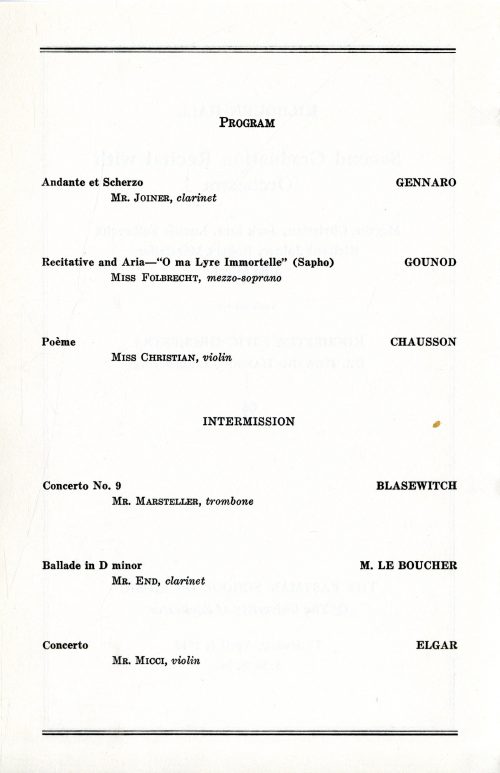

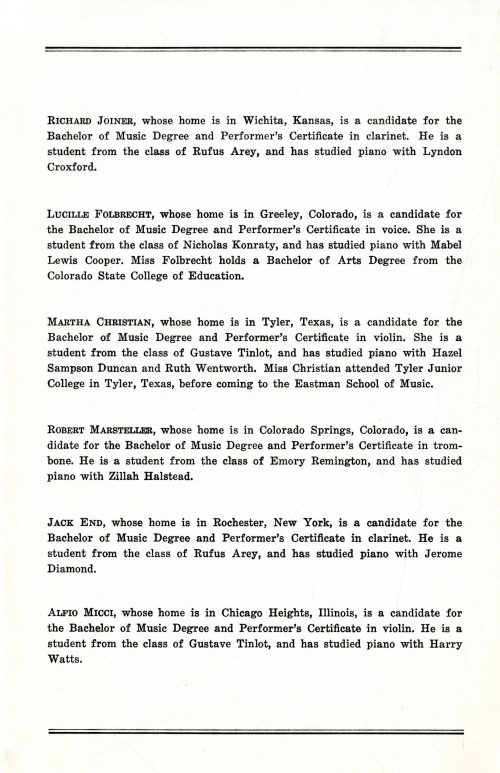

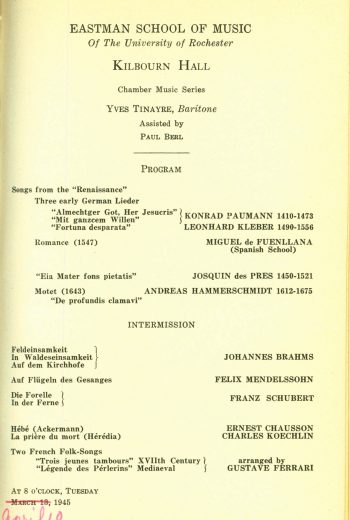

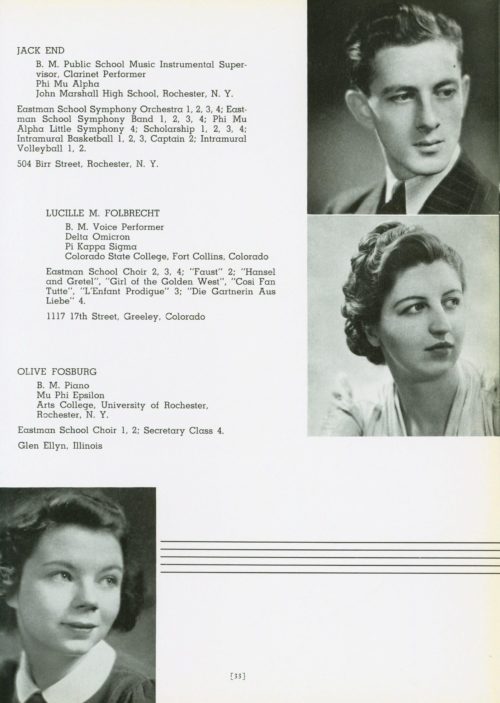

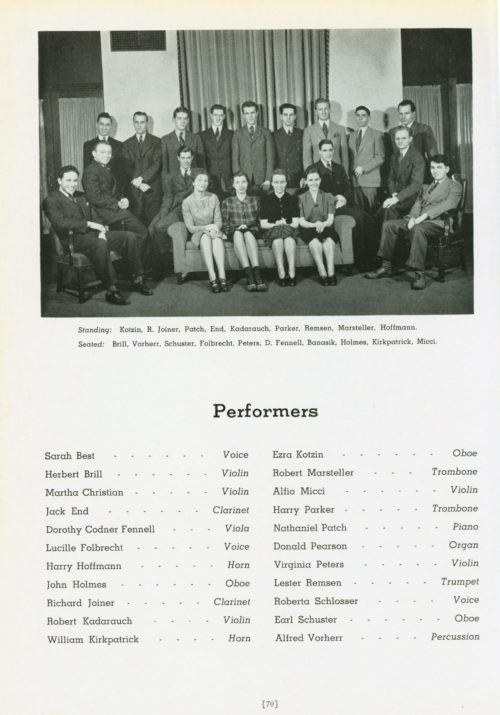

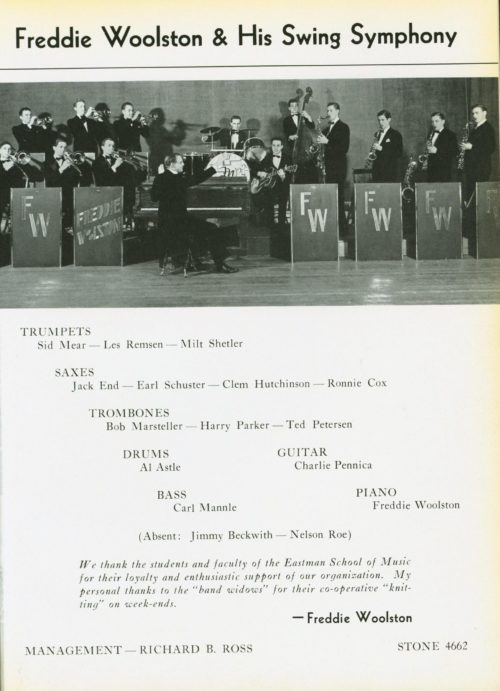

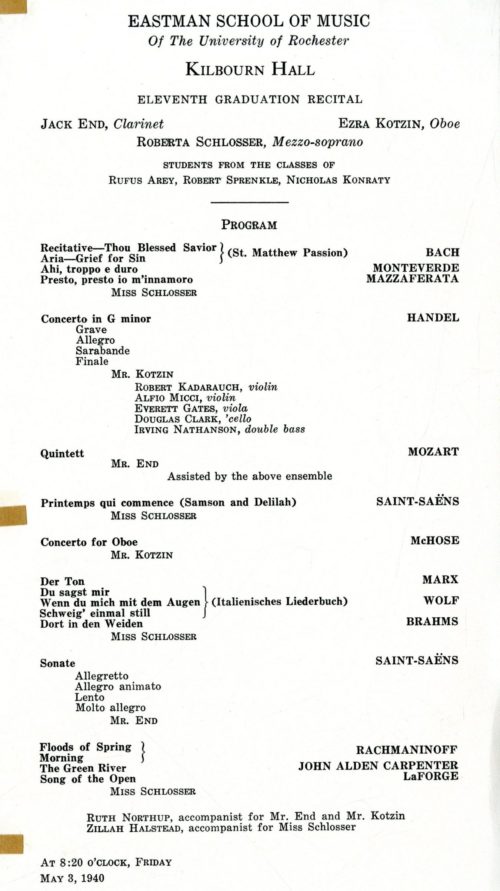

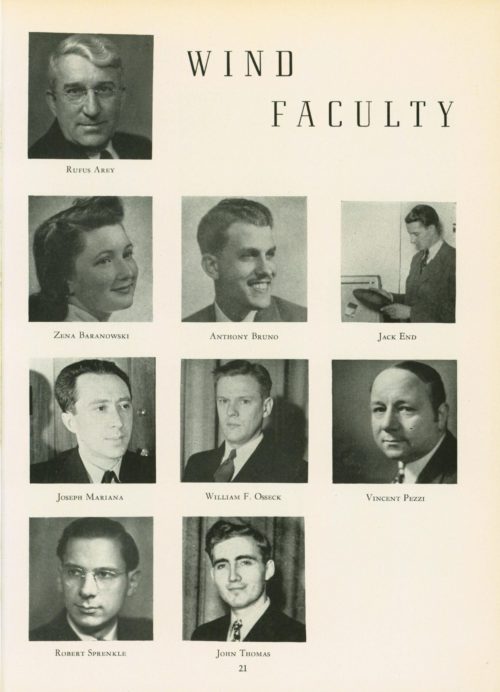

A native Rochesterian, local boy Jack End (1918-1986) attracted Eastman School attention while still in high school when, on the recommendation of Eastman clarinet professor Rufus Arey, Frederick Fennell invited the young Jack to fill out the clarinet section of the Eastman School Symphony Band. Jack End would later become principal of the section when he had matriculated as an Eastman School undergraduate.[2] He enrolled as an undergraduate at Eastman in 1936 and was a student in the class of Rufus Arey. During his undergraduate years Mr. End was a member of the Eastman School Symphony Orchestra (Howard Hanson and Paul White, conductors) and the Eastman School Symphony Band (Frederick Fennell, conductor). He was a member of the Phi Mu Alpha fraternity, and as a Phi Mu Alpha, he played clarinet in the Phi Mu Alpha Little Symphony (Frederick Fennell, conductor). Off-campus, he was a member of Freddie Woolston’s Swing Symphony (photograph in The Score 1940, displayed here). He graduated from the Eastman School in 1940 with the B.Mus. degree and the Performer’s Certificate. In fulfillment of the requirements for the Performer’s Certificate, Mr. End appeared as soloist with the Rochester Civic Orchestra under Howard Hanson’s direction (printed program displayed here). (Hanson had established the Graduation Recitals with Orchestra (later called the Graduation Concerts with Orchestra) as the vehicle by which the Eastman School’s highest-achieving performers would be promoted to the public.) Also displayed here is the printed program for his graduation recital. (On that occasion he shared the stage with his classmates Ezra Kotzin, oboist and Roberta Schlosser, mezzo-soprano; combining two or even three degree recipients into one graduation recital program was a standard procedure at the Eastman School in those earlier decades.)

Printed program for the Graduation Recital with Orchestra in which Jack End fulfilled one of the performance requirements for the Performer’s Certificate. Director Hanson had inaugurated the Graduation Recitals with Orchestra (later Graduation Concerts with Orchestra) as a performance vehicle whereby the Eastman School would showcase its highest-achieving performers. .

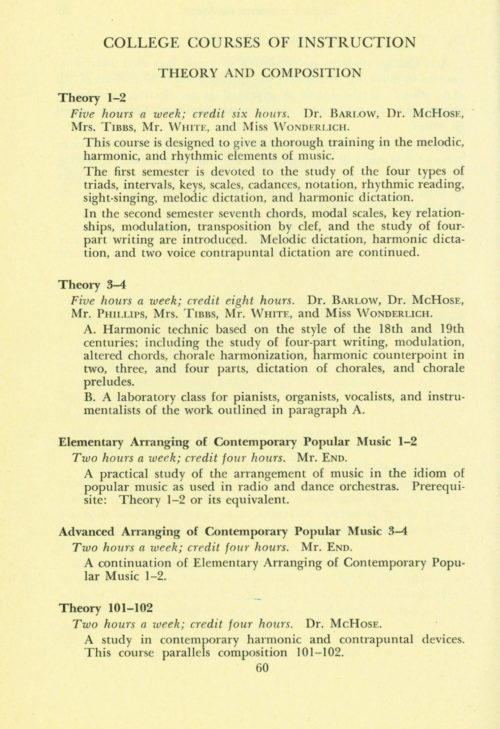

In the fall of 1940 Mr. End took his place on the Eastman School faculty as an Instructor of clarinet, a position he would hold for the next ten years. He elected graduate study in composition with Burrill Phillips, Howard Hanson, and Bernard Rogers, and professionally, during this decade he would play clarinet in the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (1943-45) and would also play his skills as an arranger for various bands, orchestras, singers, and television performances. His unique contribution to the Eastman School curriculum lay in teaching two courses in popular music arranging within the department of theory and composition. The school’s Official Bulletins (i.e. annual catalogues) promoted him as teaching this two-course sequence for five years altogether, from 1945-46 through 1949-50. The following description was published (and a scan of which is displayed here):

“Elementary Arranging of Contemporary Popular Music 1-2. Two hours a week; credit four hours. A practical study of the arrangement of music in the idiom of popular music as used in radio and dance orchestras. Prerequisite: Theory 1-2 or its equivalent.”

and its continuation:

“Advanced Arranging of Contemporary Popular Music 3-4. Two hours a week; credit four hours. A continuation of Elementary Arranging of Contemporary Popular Music 1-2.”

Notwithstanding that those courses weren’t listed in the published curriculum until 1945-46, there is some evidence that Mr. End was actually teaching arranging earlier than that. Cataloguing copy for the Eastman Audio Archive indicates that on Saturday, January 15th, 1944, a “Symposium of jazz arrangements by students in the commercial arranging course” took place, and the event featured performances by an ensemble billed as the Jack End Orchestra. (The venue is not specified, but it was likely Kilbourn Hall, since the only other venue wired into the school’s recording infra-structure was the Eastman Theater.) This was during academic year 1943-44, when no courses in arranging were promoted in the school’s Official Bulletin. The citation is revealing in that it indicates a jazz performance by Eastman School students on Eastman School premises. (It should come as no surprise that the event took place on a Saturday, when there would have been little chance of Director Hanson showing up, except to conduct a Saturday evening concert.) Further cataloguing copy for the Eastman Audio Archive indicates that a “Program of Improvisations” took place in Kilbourn Hall on March 19, 1945, when an ensemble billed as the Jack End Quartet jammed for one half-hour on nine well-known standards, including “Sweet Georgia Brown”, “Stompin’ at the Savoy”, “On the Sunny Side of the Street”, and “Get Happy”. Again, it emerges that a program of popular music had taken place in one of the Eastman School’s established venues, but this citation goes further in that it confirms that Jack End was forming and directing ensembles at school. Neither of these events could yet be considered public performances, since the Eastman School made a distinction between student concerts and public events; Jack End’s next move would therefore be to gain permission for one of his ensembles to perform publicly under the school’s auspices.

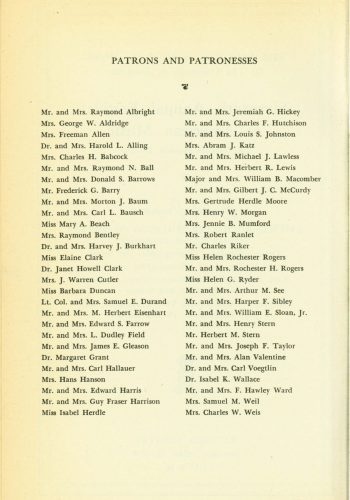

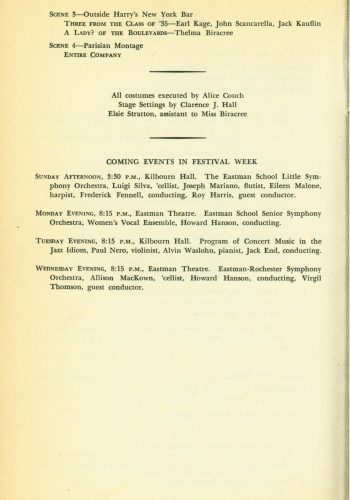

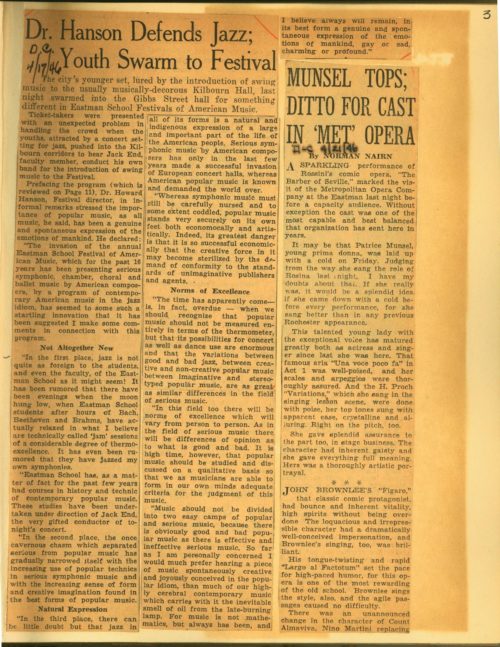

There is sufficient material to write an entry, or even an article, on Howard Hanson’s positions on jazz and popular music over the years. For the purposes of this entry, I’ll summarize by stating that in the course of time he evolved—or appeared to evolve—from outright opposition to grudging acceptance and then finally, in the era of Chuck Mangione and the Eastman Jazz Ensemble, to at least one published statement of unequivocal support. No record survives of whatever discussions may have informed Hanson’s inviting Jack End to perform at the 1946 Festival of American Music, but Hanson is on record as having used the event to publicize the view that popular music belonged in the curricula of schools of music. Did Hanson actually believe what he was saying, or was he merely capitulating to the weight of public opinion? There’s room to speculate. He also used the occasion to trot out an opinion that he would paraphrase on other occasions elsewhere: “So far as I am personally concerned, I would much prefer hearing a piece of music spontaneously creative, and joyously conceived in the popular idiom than much of our highly cerebral contemporary music which carries with it the inevitable smell of oil from the late-burning lamp.”[3] On the day after the concert, Director Hanson’s remarks were printed in their entirety—all nine paragraphs—in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle beneath the headline “Dr. Hanson defends jazz; youth swarm to festival”. Ponder the words of the headline: Dr. Hanson defends jazz. Whereas Jack End had been the one doing the hard work of coaching and teaching and directing, and had lain the necessary groundwork, and had risked ridicule at the hands of Rochester’s decidedly conservative musical audience (which at that time it most certainly was), Director Hanson had stolen the headline with his newly-arrived-at position in defense of jazz. For Hanson, that was way too easy; the hard-working Jack End deserved better. (Not incidentally, the published text of Hanson’s comments contains one omission. At the conclusion of the second paragraph, Hanson alludes to a rumor that the students “have jazzed my own Symphonies,” and as can be heard in the recording, Hanson then added the line, “But this I steadfastly refuse to believe!” evoking laughter from the audience.)

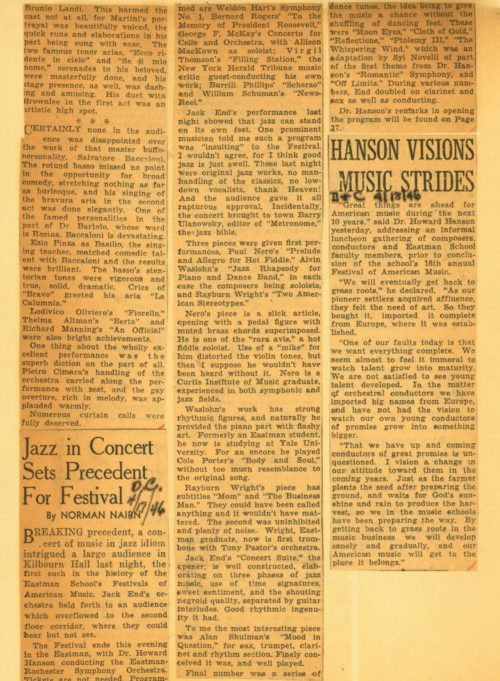

And so Jack End and his ensemble gave their performance on April 16th, 1946 before a capacity house in Kilbourn Hall, and to loud audience acclaim. The review published in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle the following day was, on balance, sympathetic to the performers and to the music. The opening paragraph of that review by Mr. Norman Nairn, music critic for the RD&C, is worth quoting in full: “Breaking precedent, a concert of music in jazz idiom intrigued a large audience in Kilbourn Hall last night, the first such in the history of the Eastman School’s Festivals of American Music. Jack End’s orchestra held forth to an audience which overflowed to the second floor corridor, where they could hear but not see.”[4] Mr. Nairn proceeded to discuss the merits of each of the programmed works, at times resorting to language that is not only dated to our ears but must surely have sounded quaint even back in 1946 (e.g. “Nero’s piece is a slick article”). Reading the review, I think it apparent that Mr. Nairn lacked the musical experience and lexicon that would have enabled him to listen to the performance, and to describe it afterwards, with real understanding.

Press item published the day after the jazz concert in Kilbourn Hall. Dr. Hanson’s remarks were published in their entirety with one exception. As the recording captured him, he added the sentence “But this I steadfastly refuse to believe” at the end of the second paragraph. Rochester Scrapbook 1946-47, pages 3 and 4. Sibley Music Library.

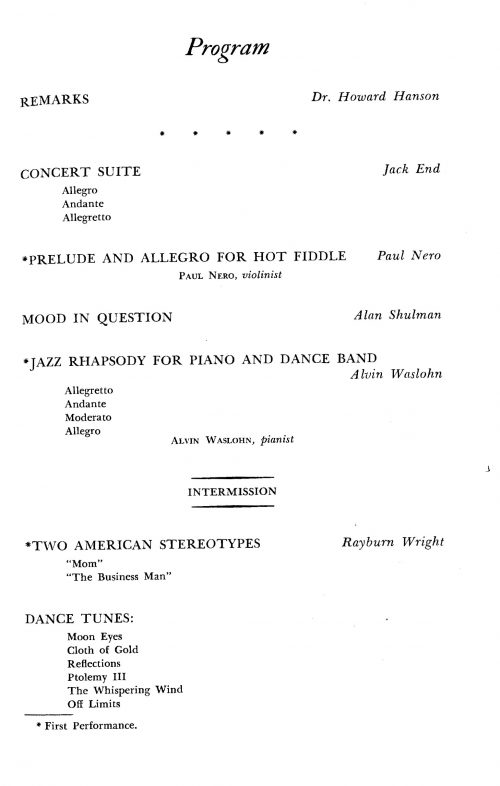

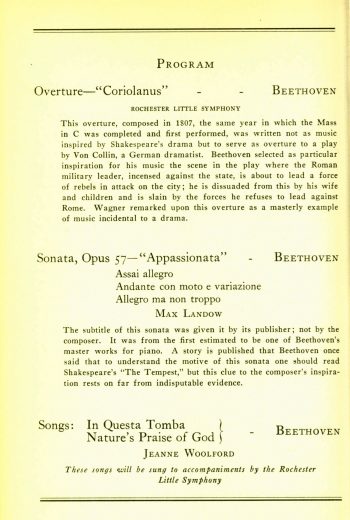

The program invites some comment. I believe the opening work, Jack End’s own Concert Suite, to have been newly composed for this event; I have found no evidence of any previous performance at Eastman. Paul Nero’s Prelude and Allegro for Hot Fiddle had already had one hearing in an Eastman School degree recital when M.Mus. degree candidate Rima Rudina, a student of Jacques Gordon, had performed it in 1944. (The printed program’s indication of “first performance” confirms what had traditionally been the Eastman School’s position with respect to public vs. private performances; degree recitals fell into the latter category.) Two American Stereotypes by Rayburn Wright, BM ’43, drew a tart comment from reviewer Norman Nairn, but don’t take it from me; the review is displayed here. The Dance Tunes that closed out the concert’s second half included an instance of what Hanson had alluded to earlier, namely, the jazzing of his Symphonies; “The Whispering Wind” borrowed a theme from his “Romantic” Symphony, and indeed, the program notes openly informed the audience of such.

At the very same Festival, in a concert on April 11th, the Eastman School Symphony Band had performed Mr. End’s twelve-minute work Floor Show under Frederick Fennell’s direction, a work that the same ensemble had introduced at a concert in May, 1943. Arguably, that work was more in line with the “concert music” rubric than the works performed on April 16th. In any event, there would be no more explicit mention of jazz at an Eastman School Festival of American Music until 1962.[5] Two years after that, Hanson retired and the Eastman School was passed to a new administration under which the wheels would inexorably turn, with the eventual founding of the department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media in 1970. Nevertheless, the 1946 performance had taken place; the master tapes and the various printed documents are extant to substantiate it. A first public performance of jazz at the Eastman School of Music was on record.

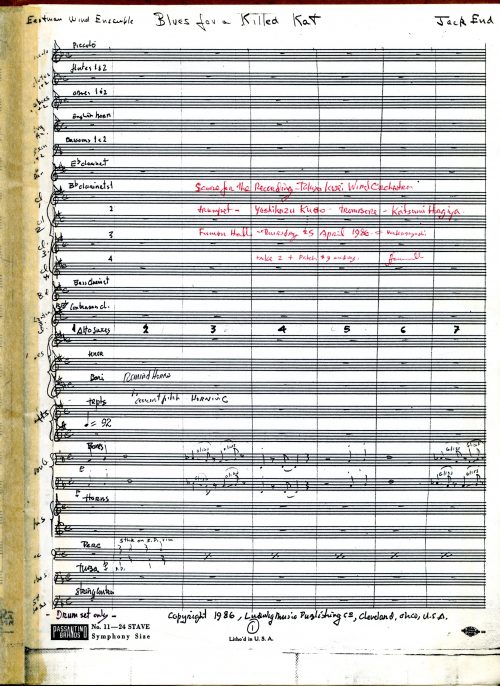

[1] Frederick Fennell, Notes to published score, Blues for a Killed Kat. Tokyo/1986. Cleveland: Ludwig Music, 1987.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Dr. Hanson defends jazz; youth swarm to Festival” by Norman Nairn. Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, April 17, 1946. Rochester Scrapbook 1946-47, page 3. Sibley Music Library.

[4] “Jazz in concert sets precedent for Festival” by Norman Nairn. Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, April 17, 1946. Rochester Scrapbook 1946-47, page 4.

[5] A concert at the 1964 Festival, given on May 4, 1962, was promoted under the rubric “THE JAZZ IDIOM” and featured guest performers The Modern Jazz Quartet performing an “Illustrated History of Jazz” after which Frederick Fennell conducted the Eastman Wind Ensemble in four works, including two by Jack End.

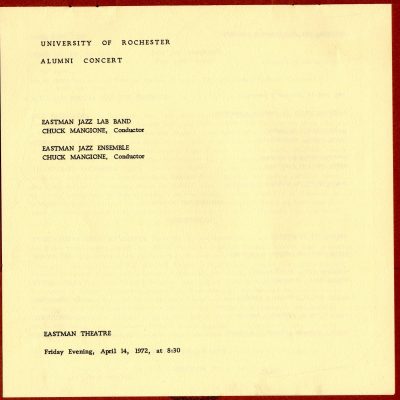

1972: Premiere of a Jack End work by the Eastman Jazz Ensemble

In 1971, the Administration of the Eastman School of Music selected 23 composers from whom the ESM would commission new works for the school’s fiftieth anniversary; Jack End, BM ’40 was among them. Further, Mr. End’s composition would be one of two jazz commissions for the 50th anniversary, the other being a new work by Oliver Nelson, which would be premiered by the Eastman Jazz Ensemble in March, 1972. In Mr. End’s case, the 50th anniversary commission represented an appropriate professional recognition of the man who had earned the right to be known as the Eastman School’s pioneer in jazz. In that decade (1940-50) when Mr. End had been a young faculty member coaching, teaching, and directing Eastman students, the Eastman School’s administrative recognition of jazz in the school’s curriculum was still some time away in the future.

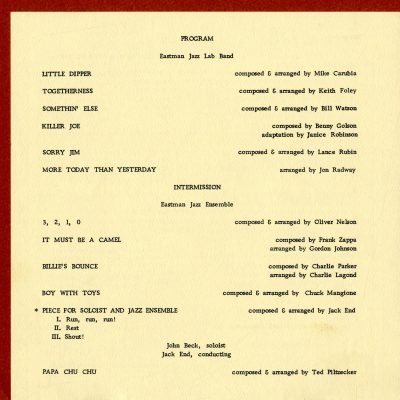

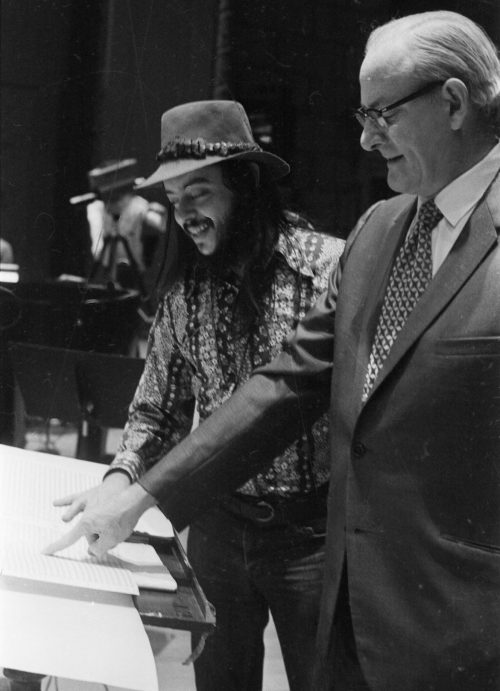

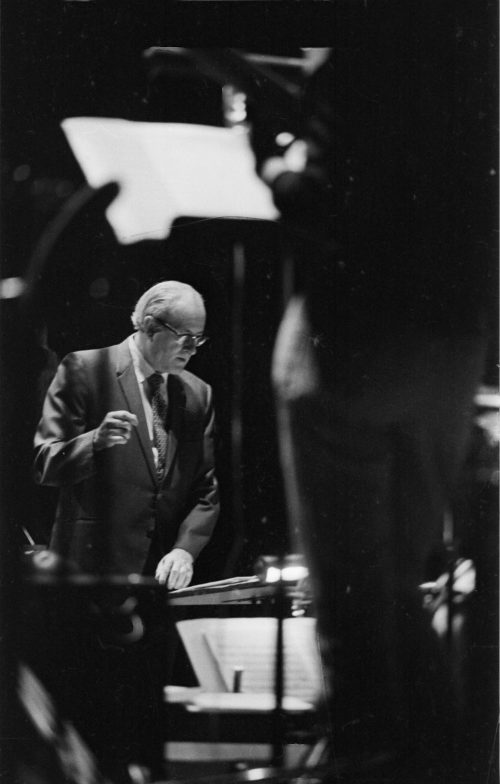

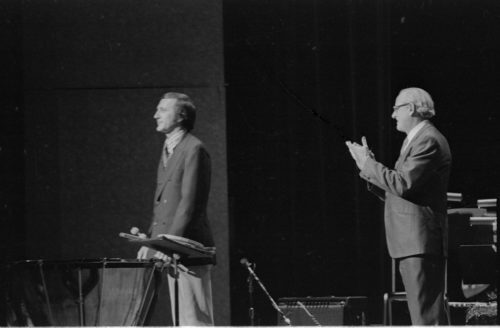

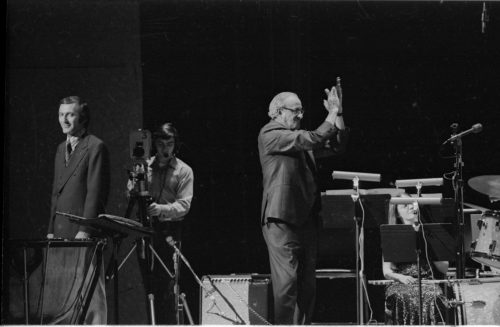

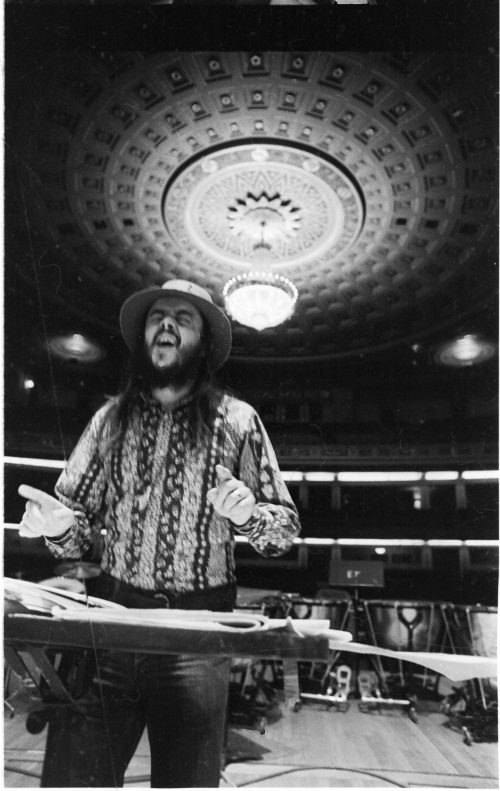

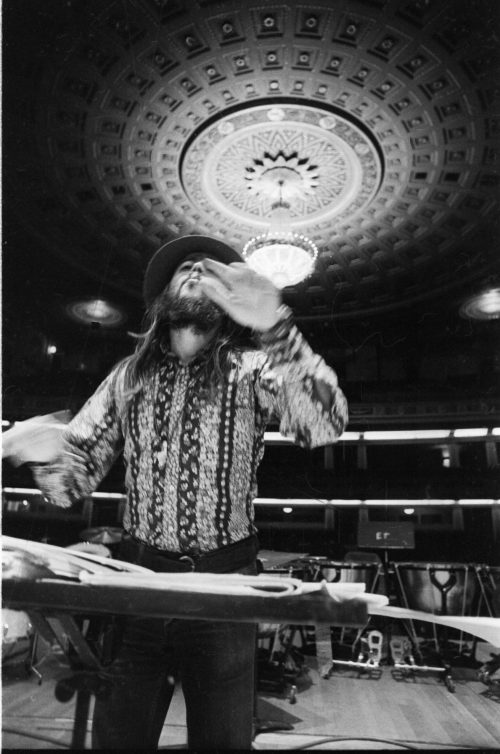

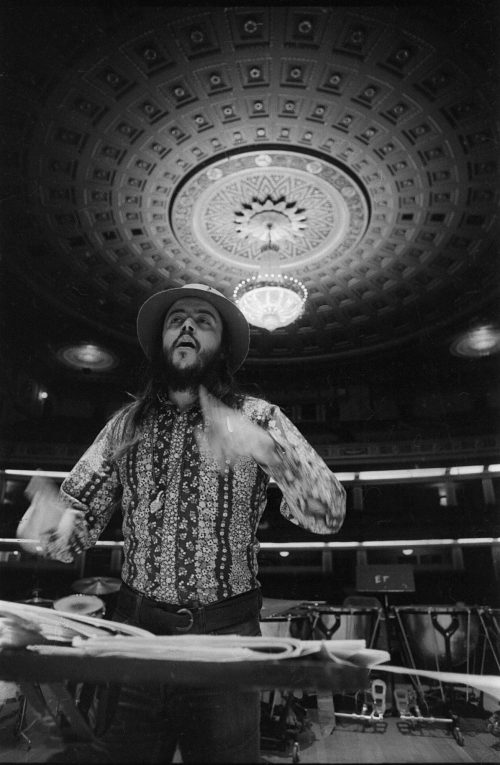

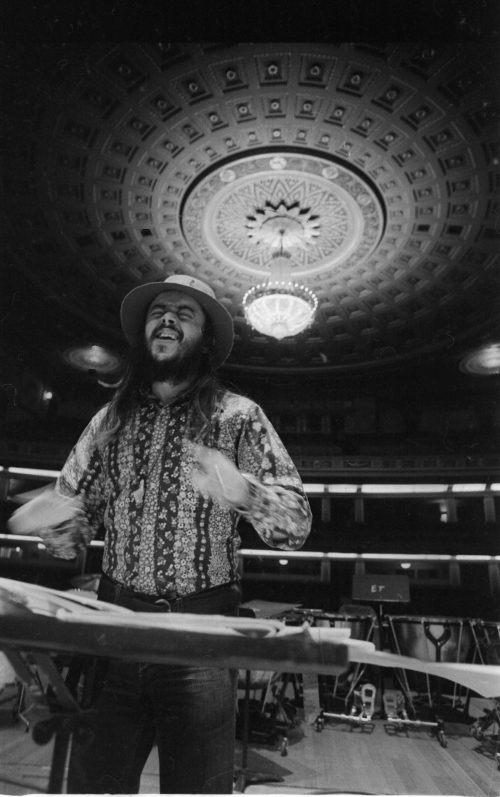

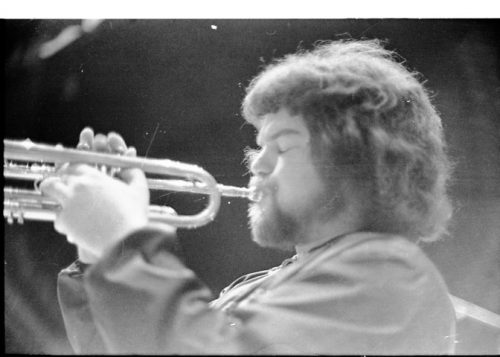

And so fifty years ago this week, on April 14th, 1972, the Eastman Jazz Ensemble gave the premiere performance of Piece for Soloist and Jazz Ensemble by Jack End, specially commissioned for the Eastman School’s fiftieth anniversary. Mr. End was guest conductor of his own work, and Eastman School Professor John Beck (who was also principal percussionist of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra) was the featured soloist. The concert, in which both the Eastman Jazz Ensemble and the Eastman Jazz Lab Band performed in turn under Chuck Mangione’s direction, was repeated the following evening. One local commentator drew attention to the new work’s big band heritage with what seemed like a thinly veiled swipe, but I’ll counter that that commentator was doing the work an injustice.[1] Jack End had grown and matured in the era of big bands and swing, and he had always practiced masterfully what he knew. Music is always evolving, and there must always be room for acceptance of earlier traditions. Photos by Louis Ouzer capture Mr. End with the members of the Eastman Jazz Ensemble on-stage in the Eastman Theater during both rehearsal and performance. Did Mr. End take any special pride in the commission? Given the work that he had done at school in the 1940s, one very much hopes that he did.

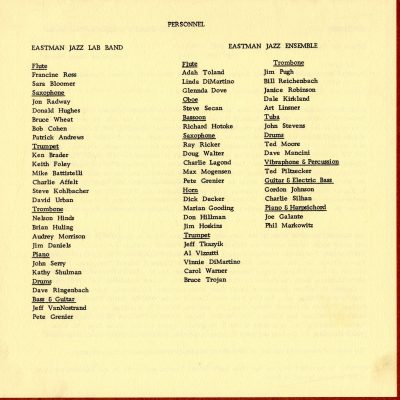

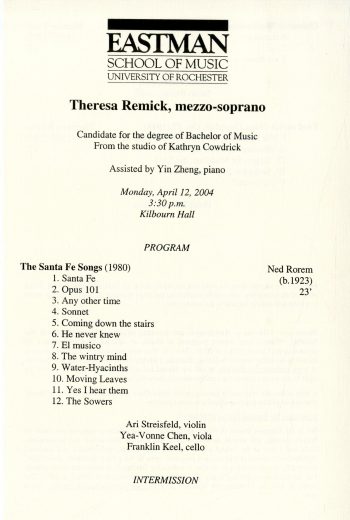

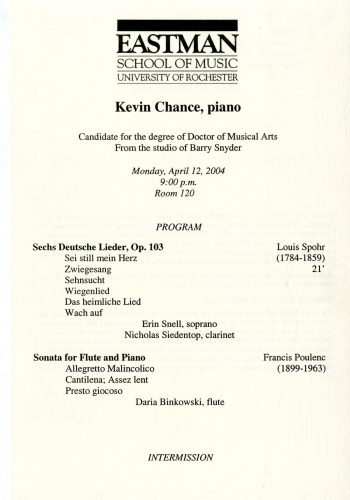

Printed program for the Eastman Jazz Ensemble/Eastman Jazz Lab Band concert of April 14th, 1972, one of the specially designated Fiftieth Anniversary Festival concerts of the 1971-72 season.

Following their premiere performance of the Piece for Soloist and Jazz Ensemble, percussion soloist John Beck and EJE Director Jack End acknowledge one another and the applause of the audience; Mr. Beck invites the EJE members to stand. Photos by Louis Ouzer.

Mr. End’s career had taken some interesting turns. After serving for ten years on the Eastman School faculty, he had resigned in 1950 to accept a position as a producer-director with WROC-TV in Rochester. Ten years later, in 1960 Mr. End had resigned his WROC-TV position to return to the University of Rochester as Associate Director of Radio and Television. In 1967 he had been appointed Deputy Director of University Relations. In that same year, he had returned to the Eastman School faculty when he was named Director of the newly founded Eastman Jazz Ensemble. He would direct the EJE for one year (1967-68), which included the EJE’s first touring experience when it accompanied the Eastman Wind Ensemble on a tour to MENC in Seattle in March, 1968. Among the local groups with which Mr. End was active was the RG&E Big Band, which he directed from 1972 until his death in 1986. Comprised of RG&E employees and retirees complemented by other local musicians; the RG&E Big Band provides a public service throughout the Rochester community at such venues as senior homes, parks, and schools. Mr. End wrote prolifically for the RG&E Big Band, altogether no fewer than 195 arrangements and/or original works; since 2018, those arrangements and original works have resided in the Sibley Music Library at the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, now known as the RG&E Big Band/Jack End Collection.[2] One band member told me back in 2008 that Mr. End’s arrangements were always guaranteed audience pleasers.

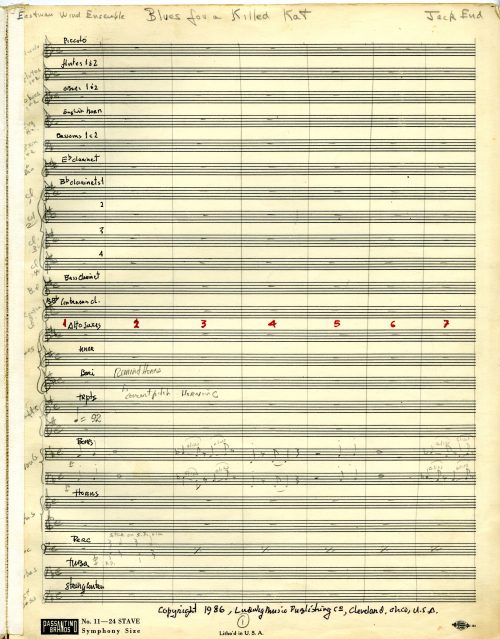

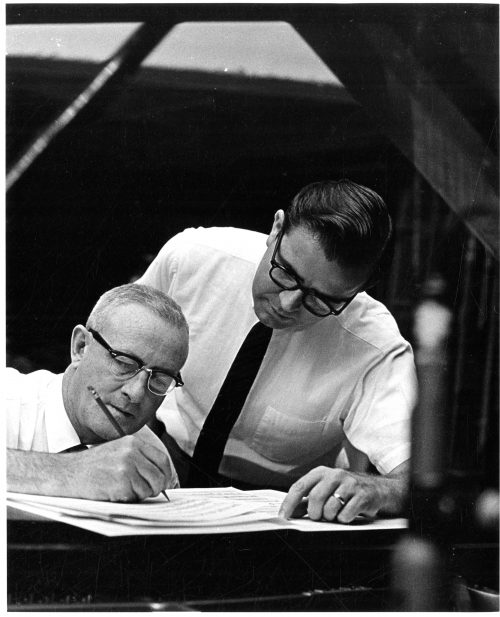

In the years since Mr. End had resigned from the Eastman School faculty, and thus was no longer a daily presence at the school, his name had remained before Eastman School audiences thanks to concert programming by both faculty and student performers. Howard Hanson had programmed Mr. End’s orchestral work Song for Sleepy Children in the 1944 Annual Symposium of American Orchestral Music.[3]. Several solo works by Mr. End had been performed in degree recitals, including his Quintet no. 1 for brass and his Song and Dance for saxophone and piano. Between 1964 and 1973 there were several performances of Mr. End’s Three Salutations, including three by the Eastman Brass Quintet. In 1971, four Eastman students premiered his Theme and Variations for String Quartet, which he had composed in response to the perceived dearth of works in variation form for string quartet. In 1973 the Eastman Wind Ensemble performed, under Donald Hunsberger’s direction, Mr. End’s The Rocks and the Sea (Maine), which was accompanied by a presentation of Louis Ouzer photographs. Dr. Hunsberger should be acknowledged as a particular supporter of Mr. End, particularly in view of the invitation for the Eastman Jazz Ensemble to accompany the Eastman Wind Ensemble on tour in 1968. In addition, another special supporter was Frederick Fennell, whose involvement with Jack End’s music had begun in 1943 when he had conducted Mr. End’s Floor Show in an Eastman School Symphony Band concert. (The work was later performed at the 1946 Festival of American Music where Mr. End and his student ensemble played their jazz program.) Mr. Fennell later conducted Mr. End’s Portrait by a Wind Ensemble at an Eastman Wind Ensemble concert in 1958. At an Eastman School class reunion in 1960, Mr. Fennell asked Mr. End for a wind ensemble arrangement of his “Blues for a Killed Cat” which had become a Jack End standard. The number expressed Mr. End’s sadness at finding a dead cat on Swan Street late one winter night. Mr. End obliged Mr. Fennell, and the Eastman Wind Ensemble performed the arrangement under Mr. Fennell’s direction at the 1962 Festival of American Music, together with another End original work, Variations in the Style of Sauter. One quarter-century later, Mr. Fennell published his own edition of Blues for a Killed Kat (Cleveland Music, c1987; the difference in spelling of the title’s last keyword was not accounted for); shortly before that, soon after Mr. End’s passing in 1986, the Tokyo Kosei Windorchestra recorded the work under Mr. Fennell’s direction. In addition, the RG&E Big Band/Jack End Collection cited previously holds an arrangement of this number that Mr. End made for the RG&E Big Band in 1976.

Mr. End would retire from his University of Rochester position in 1975. His post-retirement activities would include continuing to direct the RG&E Big Band until his death in 1986.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that the two concerts on April 14th and 15th, 1972 were Chuck Mangione’s valedictory appearances as Director of the Eastman Jazz Ensemble. Mr. Mangione had not renewed his faculty contract past the 1971-72 academic year; he has gone on record regarding the circumstances of that time. His four years at the helm of the Eastman Jazz Ensemble had been years of tremendous achievement for the EJE, which will be acknowledged in later “This Week at Eastman” entries.

[1] “Mangione program pleases big Eastman jazz crowd” by Theodore Price. Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, April 16, 1972. Rochester Scrapbook March-May 1972, page 89. Mr. Price characterized Mr. End’s piece as “cast in the mold of the Glenn Miller era” and “evocative of a bygone era of jazz expression” and ended with his commentary with the sentence “His new Piece is often thin on orchestration, concentrating most of the time on backup for the soloist, sounding like re-warmed swing the rest of the way.” Re-warmed. Diss alert!

[2] The collection’s finding aid is accessible at the Sibley Music Library website

[3] In 1935, Hanson had launched two Symposia series that would serve as vehicles for the performance and promotion of new orchestral works: a fall Symposium of American Orchestral Music, featuring works by American composers from across the nation, and a springtime Symposium of Student Works for Orchestra, featuring works composed by Eastman School students. The two Symposia reflected Hanson’s innate affinity with the orchestra as a medium of musical performance.

The Weekly Dozen

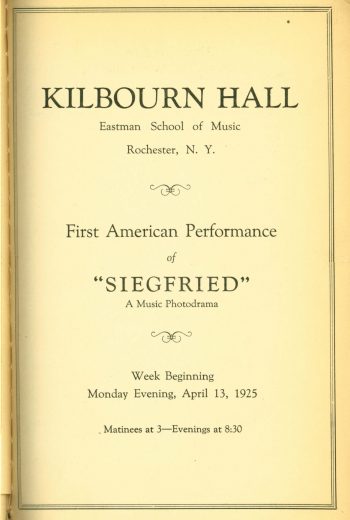

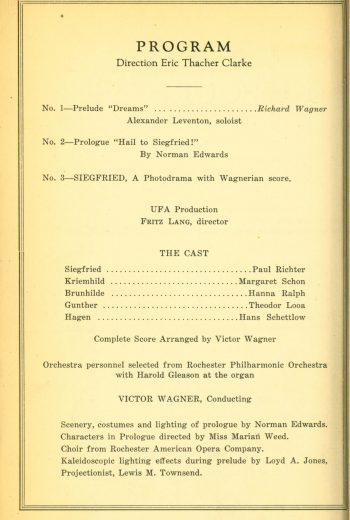

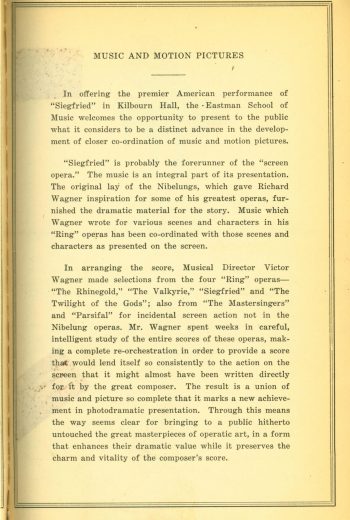

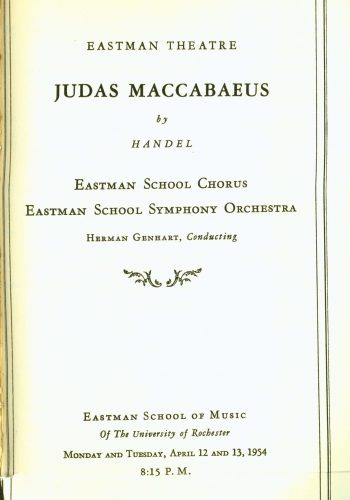

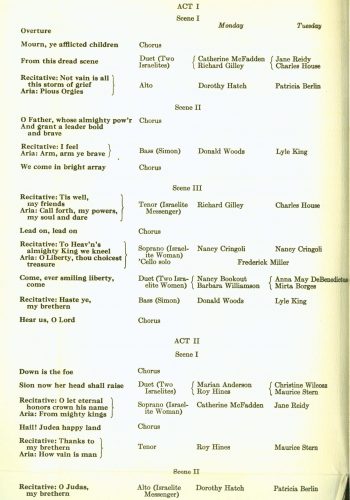

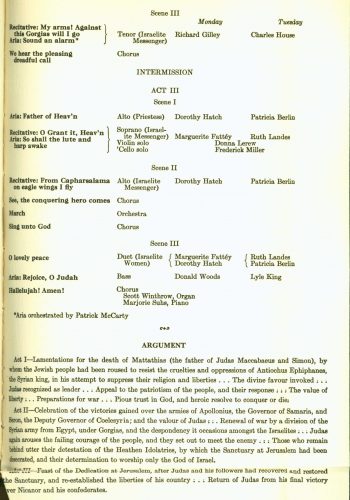

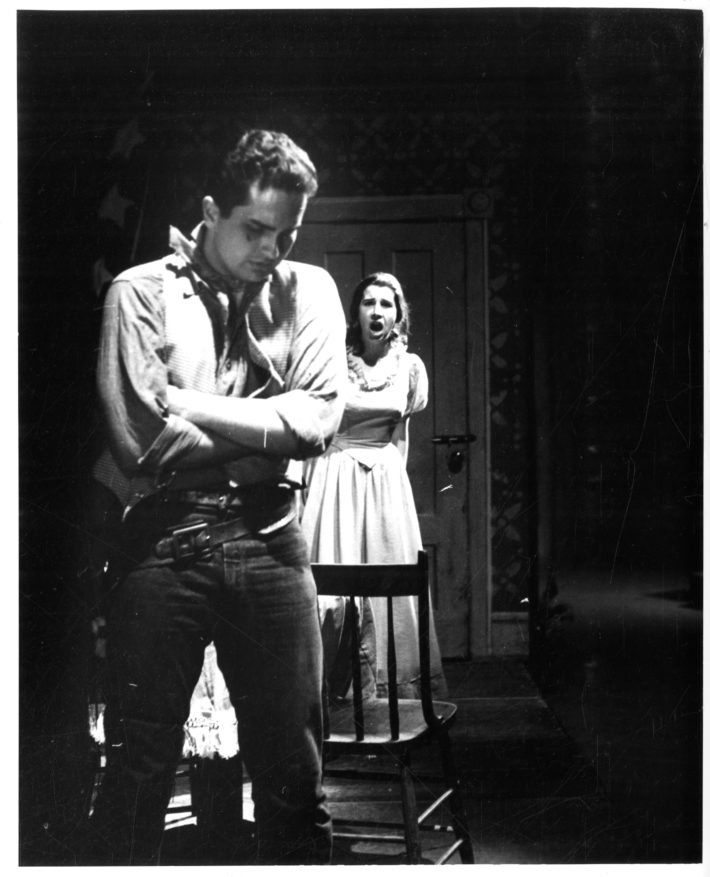

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we recognize two illustrious choral showcases, performance by members of that never-dull Rochester American Opera Company, a photo-musical Siegfried event that shines the spotlight on the 1920s film activity around the Eastman School, and as always, some superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.