March 28th-April 3rd: OSSIA does John Cage’s Song Books

March 28, 20222001: OSSIA scores with John Cage's Song Books

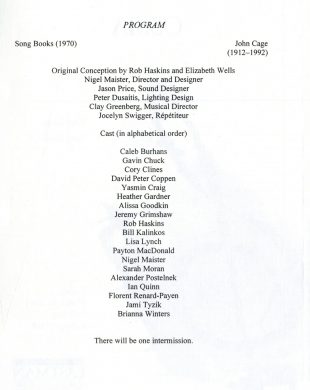

Twenty-one years ago this week, on Friday, March 30th, 2001, “We connect Satie with Thoreau” was the leitmotif and overarching theme when OSSIA took the stage with a knock-out performance of John Cage’s Song Books. Before a capacity audience in Kilbourn Hall, a cast of 19 performers interpreted theatrically and musically the complex, sprawling, and challenging work—by means both vocal and instrumental, and using amplification and electronic media, as well as all manner of realia and props as suggested in the score and/or as realized by the cast members working under inspired direction. Song Books, a complex stage piece uniting theater and music, defies easy classification; it is generally regarded by admirers and enthusiasts of John Cage (1912-1992) as the composer’s magnum opus, the quintessence of his creative output.

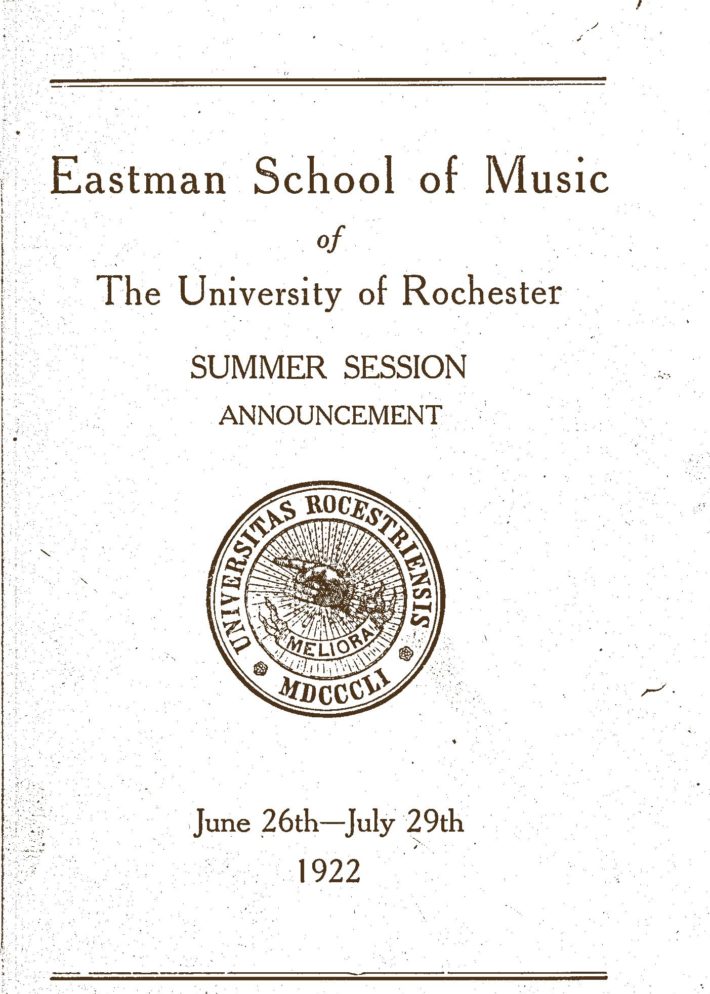

At the Eastman School of Music, the music of John Cage was only slowly received at first. Taking into consideration those catalogued performances captured and preserved on tape, on disc, or on server, the first performance at Eastman of any music by Cage was in the spring of 1961, followed by a performance of another Cage work one year later. Nothing more of Cage was heard at Eastman in the decade of the 1960s. In the 1970s, there seven recorded performances that included music by Cage; thirteen in the 1980s; thirteen in the 1990s; and a total of 26 since the dawn of the new millennium. Altogether, while there has been no huge rush of affection, a steady increase in local interest is clear. In the past twenty-five years, the involvement of OSSIA has been one factor in this, and since the 1970s, Eastman’s percussionists have consistently performed certain Cage works: the three Constructions, Living Room Music, Double Music, and Amores.

The OSSIA production of Song Books grew out of an original conception by Rob Haskins, DMA 1997, Ph.D. 2004 and Elizabeth Wells, Ph.D. 2001—truly a meeting of minds, given where each was coming from. Wells brought a grounding in theater studies (including her dissertation research on Bernstein’s West Side Story) and in stage management (having served in that capacity for operatic productions at Eastman and elsewhere); and Haskins brought an ardent primary interest in Cage’s music as both scholar and performer. While at Eastman, Haskins took part in several performances of Cage’s music under the auspices of both OSSIA and Musica Nova, and also wrote program notes and liner notes for recital programs and commercial CD releases. His doctoral dissertation (2004) dealt with Cage’s number pieces, and his later scholarship would include publication of a biography of Cage (Reaktion Books, 2012). Technical and other support for the OSSIA production came from within Eastman and from the River Campus: direction and design by Nigel Maister, Artistic Director of the U of R’s International Theater Program; sound design by Jason Price, MM 2004, DMA 2005; lighting design by Peter Dusaitis, BS 2000, MS 2001; musical direction by Clay Greenberg, BM 2001; and the répétiteur was Jocelyn Swigger, MM 1997, DMA 2001. From initial conception through to design and direction, the production was supported by a brilliant team who collaborated with a unity of purpose.

Song Books (Solos for Voice 3-92) was commissioned by the Gulbenkian Foundation and was composed in August-October, 1970 while Cage was residing in Stony Point and then in New York City. The work was dedicated to Cathy Berberian and Simone Rist, who, together with Cage himself, were the featured interpreters of Song Books in its premiere performance at the Journées de Musique Contemporaine (Paris) on October 26th, 1970. The work was published in two volumes by Henmar Press in 1970. There has been considerable analysis of, and scholarly attention to, the work. For the purpose of this brief discussion, in form and content Song Books is comprised of 90 so-named Solos for Voice that are numbered 3 through 92. (What is not unrelated, Cage had earlier published his Solo for Voice I (Henmar Press, 1930) and Solo for Voice 2 (Henmar Press, 1960).) The General Directions on page 1 lay out the composer’s vision as to execution and interpretation, in which the element of chance is inherent from the outset, since any number of the Solos may be performed by one singer or by any number of singers, and in any order desired; any given Solo may recur in a given performance; Solos may be super-imposed upon one another, and other works by Cage may similarly be super-imposed (the composer offers some recommendations in that regard). Cage offers directions for each individual Solo, but these at times are merely suggestive, or else to be disregarded altogether. Regarding the means of execution, each Solo fits into one of four categories that Cage has delineated: Song with Electronics; Theater; Theater using Electronics; and, Song (i.e. strictly vocal). Further, each Solo is pre-determined by the composer as being relevant or irrelevant to the concept “We connect Satie with Thoreau,” a line drawn from Cage’s own diary (published in 1967 under the title Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)). For those Solos that are sung or otherwise intoned in some manner, the texts were drawn from an eclectic number of writers: Henry David Thoreau, Friedrich von Schiller, Erik Satie, Norman O. Brown, Marshall McLuhan, R. Buckminster Fuller, and Merce Cunningham. The chosen texts all speak to Cage’s outlook and philosophy at the time of composing this huge work; in particular, the use of Thoreau’s words introduces the concept of anarchy into the work. The meanings and implications of Song Books have been amply treated in Cage scholarship, and will likely continue to be examined and re-examined as time passes.

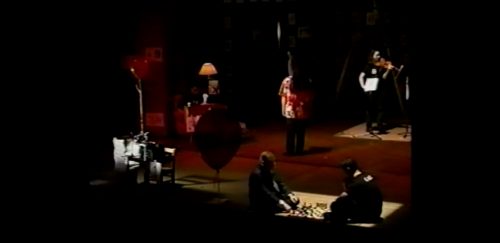

Any performance of Song Books that is true to the letter and spirit of the composer’s directions will, of necessity, entail a richly and dynamically theatrical experience suffused with virtuoso musical elements. Further, the composer’s directions and recommendations release the potential for using the entire space beyond the stage. The OSSIA production made use of the entirety of Kilbourn Hall, with cast members leaving the stage to perform various Solos in the house among members of the audience. Even the Kilbourn Hall stage manager’s/chief usher’s routine statement of greeting and emergency preparedness (“Good evening, and welcome to Kilbourn Hall. At this time we ask . . .”) became a part of the dramatic proceedings, for the action had already been underway for twelve minutes when the stage manager/chief usher took his place on-stage to make his announcement. The announcement was immediately echoed in turn by two members of the cast who were positioned nearby (!). The lighting design was particularly effective; the stage was essentially always darkened, with light thrown specifically on the centers of action wherever they happened to be in the given moment.

OSSIA was in its fourth year at the time of this production, having debuted in October, 1997. Musica Nova had previously debuted in 1966 as the Eastman School’s first group dedicated exclusively to the performance and interpretation of new music, but OSSIA took the concept a step further with its student-managed, student-governed model. Several graduate students who had participated in OSSIA’s founding were still present for the John Cage production; two members of the Song Books cast had been featured composers in OSSIA’s 1997 debut concert. Ultimately, the Song Books production proved to be formative in more than one respect. For Dr. Rob Haskins, it was the realization of an artistic goal that was then parlayed into a continuing role as artistic advisor to other productions of Song Books by other groups elsewhere. For those enterprising Eastman students who eventually founded the award-winning group Alarm Will Sound, the production provided inspiration towards much of what that group would become. As Alarm Will Sound Artistic Director and Conductor Alan Pierson has noted in an information video uploaded to the AWS channel on YouTube, the 2001 Song Books production “. . . really was the beginning of a lot of our thinking about theatricality and its role in musical performance.” In other words, the OSSIA production had legs far beyond a single evening in Kilbourn Hall. Those who originated this project’s idea and those who supported it are to be congratulated. For its thoughtful ingenuity and creativity, and for its virtuosity in execution, the OSSIA production of Song Books deserves to take its place in the annals of great performances at the Eastman School of Music.

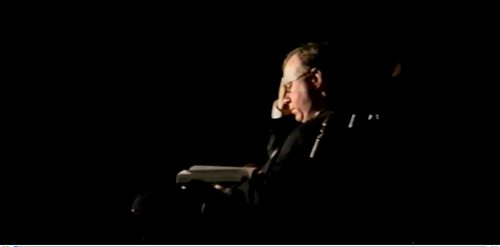

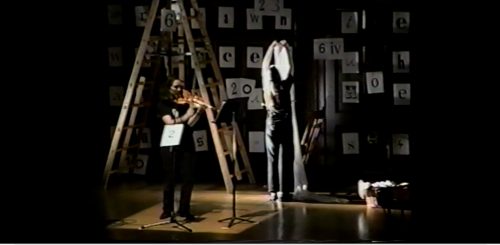

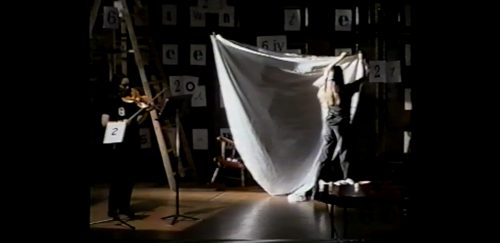

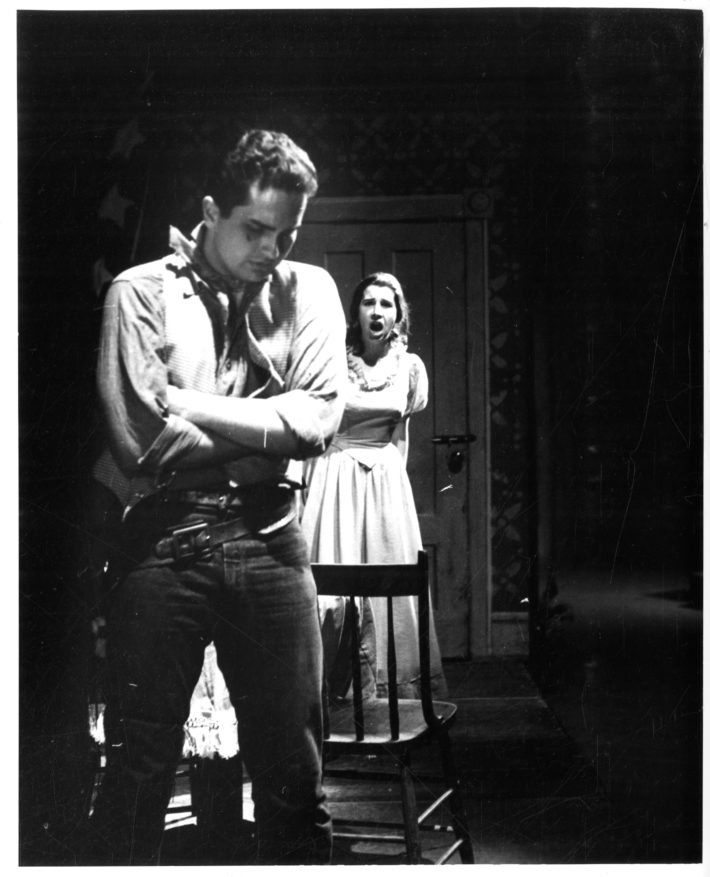

IMAGES FROM THE PERFORMANCE:

At this time the Eastman School’s capture and archival retention of school-based concerts is limited to the audio aspect. CD service copies of the March 30, 2001 performance are available for listening at the Sibley Music Library’s Recordings/Reserves department. In 2001 Dr. Rob Haskins made a gift of a VHS video-cassette of the performance, privately made, to the Eastman School of Music Archives. Digital files in Quick Time Movie format were obtained from the VHS tape in the Eastman School’s office of Technology & Media Production and are secured on an Eastman School server. I am displaying herewith a number of screen-captures from the digital copy made from the 2001 analog video in the hope of sharing something tangible of the performance and its amazing energy and creativity. Beyond the most basic attention in Adobe Photoshop, no effort has been made to enhance the images.

PART I of performance

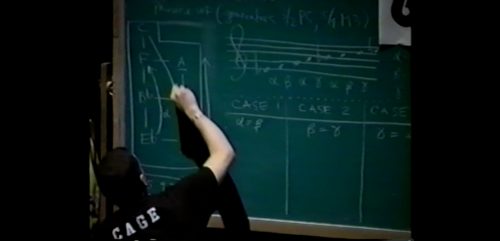

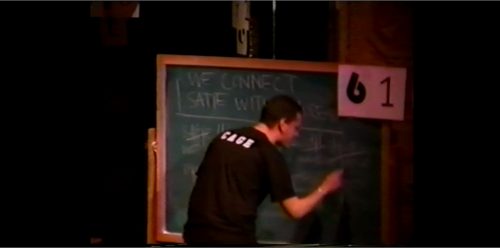

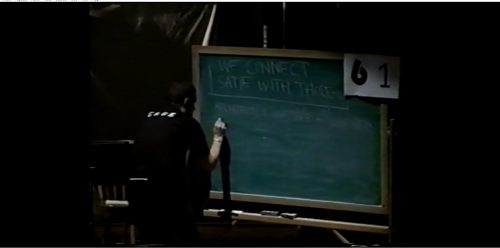

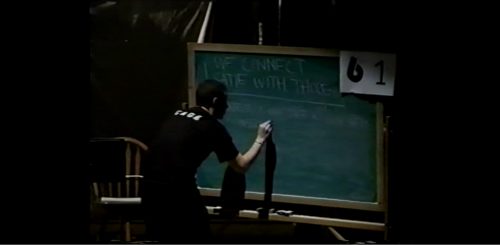

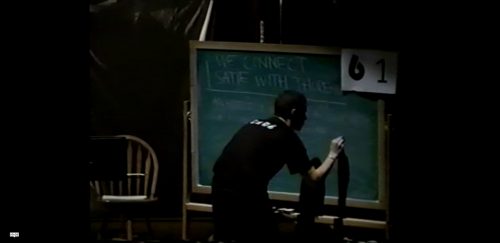

This sequence of screen-caps depicts the performance’s opening gestures, in fact preceding the customary announcement that the Kilbourn Hall stage manager makes to the audience. For the next three to four minutes the sounds of audience members chatting and taking their seats can be heard. While the sound of a narration being read comes the loudspeakers, at 00:30, the first performer is reading while seated in a rocking chair, and at approximately the 3:00 mark he moves to a writing table bearing a typewriter, which will be the prescribed instrument for several of the theatrical Solos. By 4:42 a second performer is standing at the blackboard, likewise for a theatrical Solo, this one lasting several minutes as he thoughtfully writes on the board and occasionally steps back to survey his work. The blackboard, like the typewriter, will be the site for several Solos.

At around the 12:00 mark the Kilbourn Hall stage manager appears on-stage, happening to be in close proximity to the performer at the typewriter. “Good evening, and Welcome to Kilbourn Hall. At this time we’d like to ask you to take a moment to turn off all cellular phones, paging devices, wristwatch beeps, and alarms. For your safety . . .” Immediately after he finishes his announcement, the announcement is echoed by two performers in turn who are standing nearby on the stage.

Having been given a sheet of paper by the typist, this performer is performing a vocal Solo while folding the paper into a paper airplane, which she then launches into the air at 15:13.

In the first and second images we need instances of super-imposition of several Solos, contributing to a complexity which the viewer will interact with and deal with as he or she sees fit. At 17:12 one performer sings a vocal Solo to the accompaniment of percussion. At 18:55, the performer by the blackboard is continuing to rest until his next prescribed Solo.

Around the 26:00 mark, these two performers emerge and perform a Solo that constitutes a lively comedy sketch, provoking much audience amusement.

At 28:00 the performer is engaged in Solo for Voice 64, shouting the text NICHI NICHI KORE KO NICHI at highest volume “like a football cheerleader” as the Directions prescribe, and audibly keeping score of his chant on the blackboard.

Solo for Voice 54 (Theater), one of several Solos prescribing a departure from the stage and then a return in some fashion. At 28:45 the performer appears to be pondering his move; at 28:53 he crosses the stage, walking past the performer engaged with her instrument; by 29:03 he has crossed to the edge of the stage and has moved aside the desk chair. The Directions prescribe that the performer leave the stage “by going up (flying) or by going down through a trap door” but in this instance, departure by a trap door is simulated (between 29:03 and 29:14) by the performer sliding beneath the desk and lowering himself over the edge of the stage to the house floor. By 30:26 he has returned to the stage, this time wearing an animal head as per the Directions. At 30:37 he replaces the chair from where he had moved it, and looks around the stage before leaving it for good at 30:49.

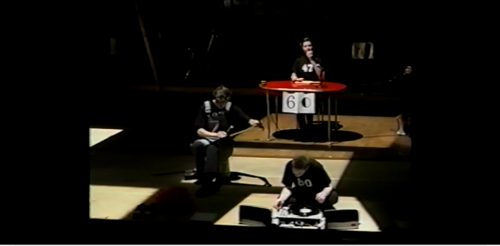

At 32:15 the viewer sees another instance of super-impositions; performers are in situated in no fewer than five sites on the stage, each one (or each pair) engaged in a separate Solo, while through the audio three separate vocal events are heard concurrently.

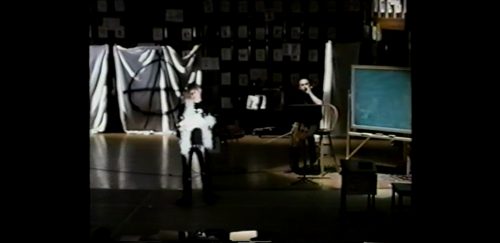

At 36:15 a slide of Henry David Thoreau’s likeness is projected onto one of the sheets (the projection is itself a Solo), and eventually at 42:08, on the same sheet where Thoreau’s likeness had been, one performer is drawing the A=Anarchy symbol.

The actions in Part I eventually accelerate in tone and pitch to an anarchic climax. Through the audio we continue to hear three separate vocal events and at 44:00, more than one performer has crossed from the stage into the house and is throwing sheets of paper all about. At 44:37 comes a recurrence of Solo 64 whereby the performer is again standing at the chalkboard, now shouting urgently and angrily into a megaphone while keeping score on the chalkboard with violent deliberation. At 44:46 we see the back of one of the sheet-throwers as she makes her way back to the stage. At 45:44, sheets of paper are now being flung from the stage. Meanwhile, the typist has serenely been continuing his action, apparently oblivious to all the rest. The mayhem ceases when high-pitched audio feedback at 46:00 (itself a Solo) sends all the performers but one (the typist) running to backstage and the lights are cut. The typist serenely carries on while the sound of a rainstorm is heard (itself a Solo).

At 46:40 five performers return to the stage under a glow of red light; four are standing in a line with a fifth standing in front of them at center stage. At 46:46 he begins intoning the Kilbourn Hall announcement (“Good evening, and Welcome to Kilbourn Hall . . .”). At 47:06 he begins to shout as he continues the text, his voice rising in urgency and volume; he completes the announcement just as the curtain closes before him.

PART II of performance

Another Solo performed at the chalkboard; this time the evening’s leitmotif is explicitly written out on the board.

A change has occurred at the side table. The typewriter has been removed and the typist has stepped away; a new Solo (Theater) is being performed there.

Two performers in an apparent collaboration, the one vocalizing and the other on violoncello and kazoo.

This performer executed a Solo for Voice by singing a portion of the Queen of the Night’s aria from Mozart’s The Magic Flute. The aria was followed by an amusingly extended sequence of bows and kiss-blowing, after which the performer left the stage looking back and waving at the audience.

At 32:09, the performer holds open a codex for the other to read from; at 34:48 the one performer is making an object while the other hands material to him for the making (in this instance, a wad of chewing gum); at 35:18 the codex is handed back.

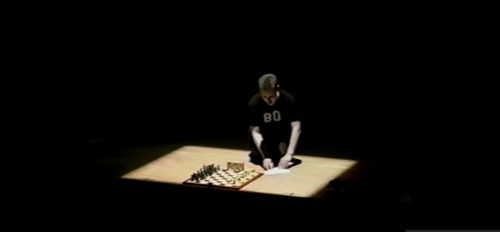

At 34:20, the performer is executing a Solo whereby he plays both sides of a game by himself, and using the time clock while doing so. At 35:55, a second Solo is super-imposed when the performer sips from a French cognac glass.

The cast members acknowledge applause at the end of Part II. At 43:07, Nigel Maister, Director and Designer; and at 44:21, Rob Haskins is at center.

The Weekly Dozen

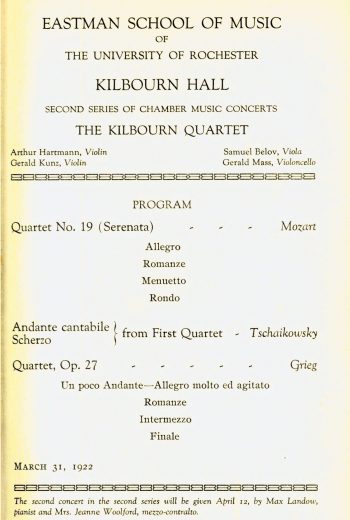

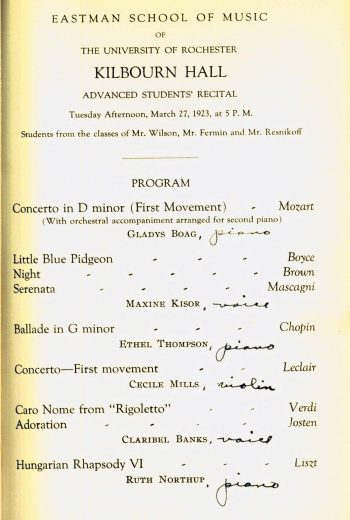

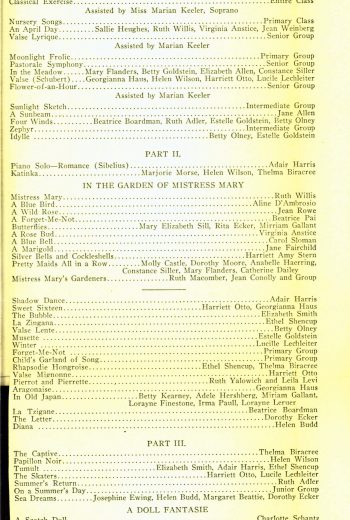

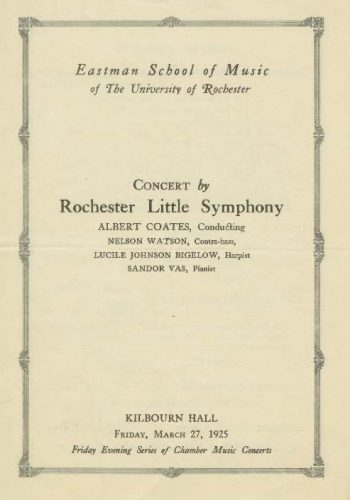

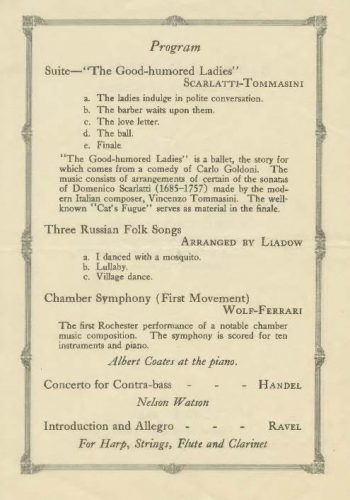

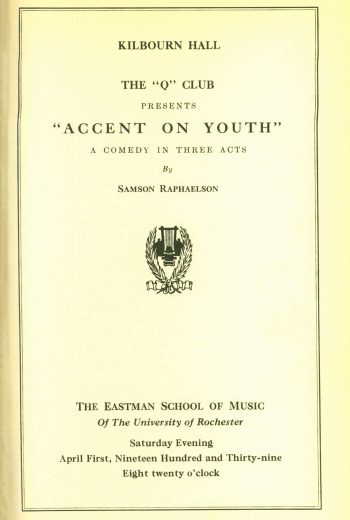

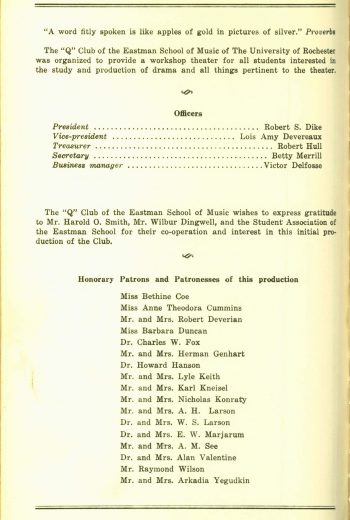

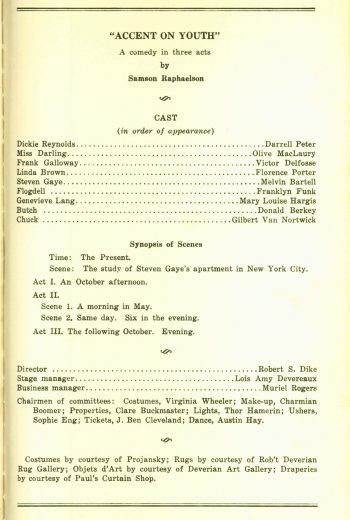

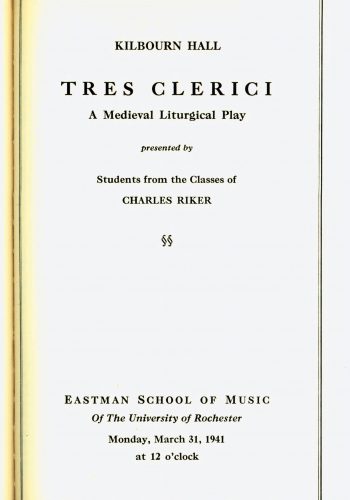

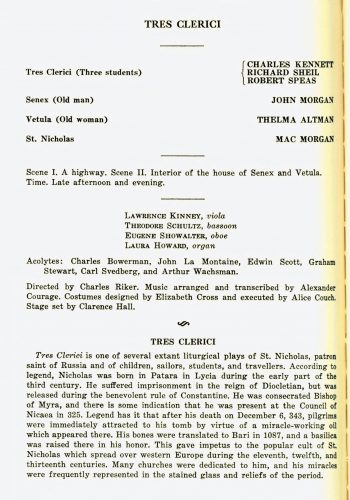

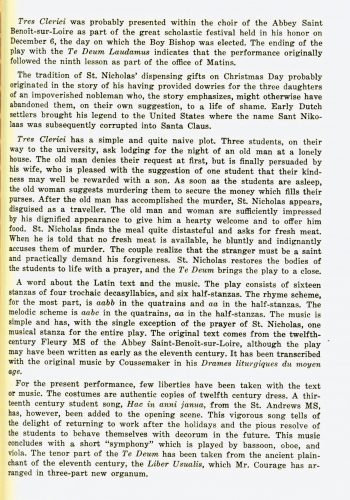

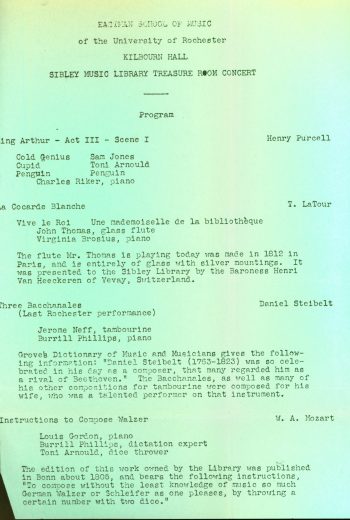

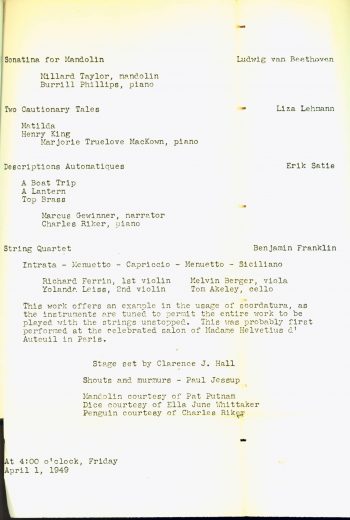

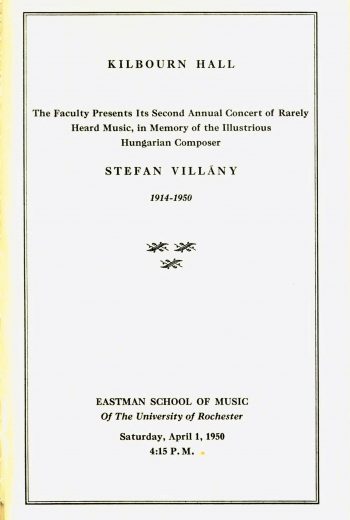

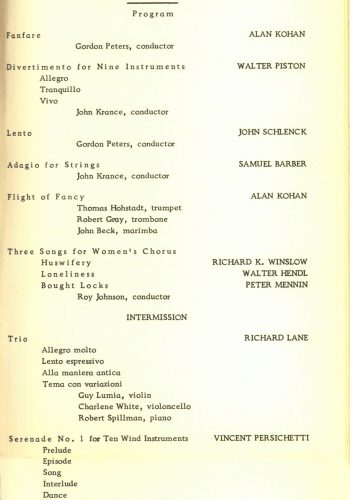

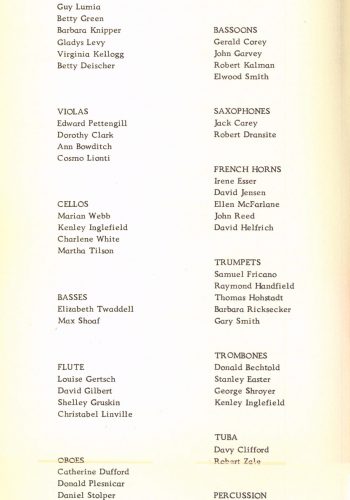

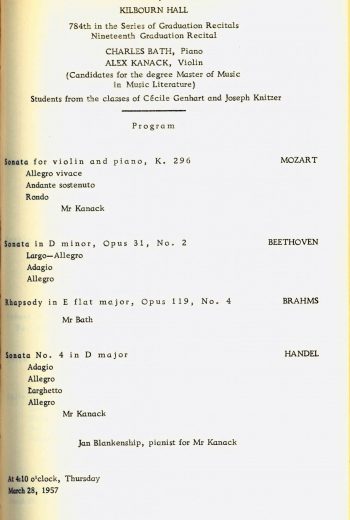

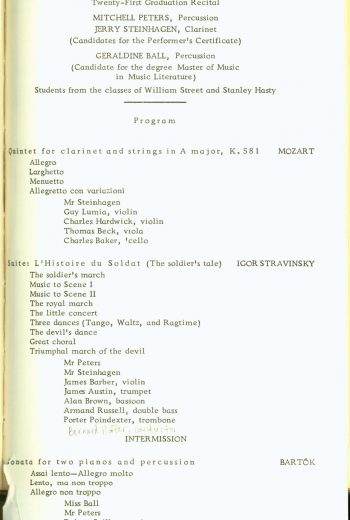

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we recognize one of the earliest chamber music recitals taking place in Kilbourn Hall, this one featuring the Eastman School’s first resident string quartet, the illustrious Kilbourn Quartet; two dramatic productions, such as used to take place in Kilbourn Hall; two recitals from the era when the school had active chapters of more than one fraternity and sorority; a recital featuring content from the Treasure Room of the “Old” Sibley Music Library (today such treasures are housed in the Special Collections vault); an April Fools’ Day gag recital put on by members of the faculty (in an earlier time, there were a number of such light-hearted gags for April 1st year after year); one in the series of Student Symposia of Works for Orchestra, that being one of Hanson’s American music initiatives (and this particular Symposium in 1955 featuring three composers who later archived their manuscripts in the Sibley Music Library); and finally, superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.

►March 31, 1941

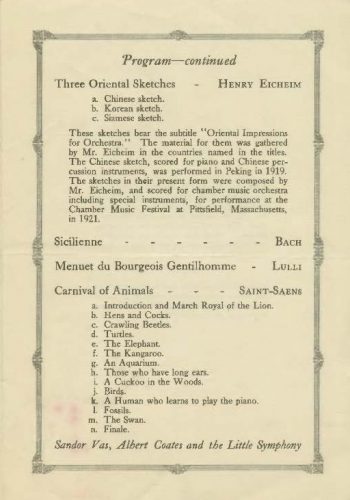

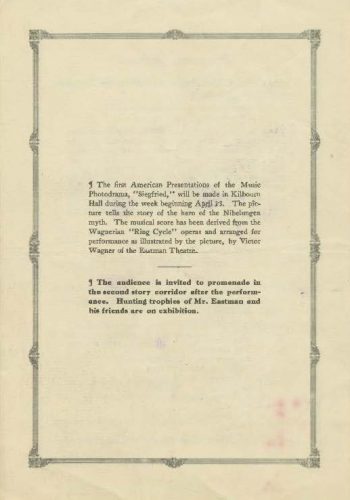

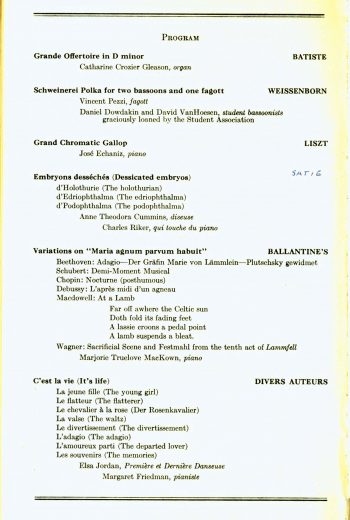

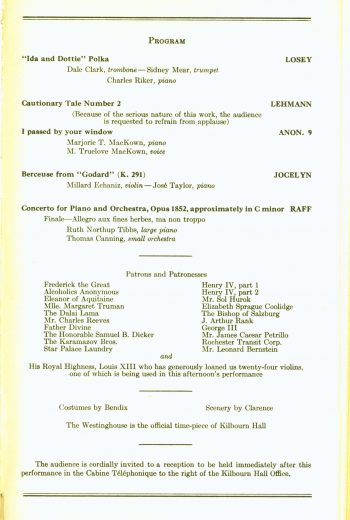

►April 1, 1949

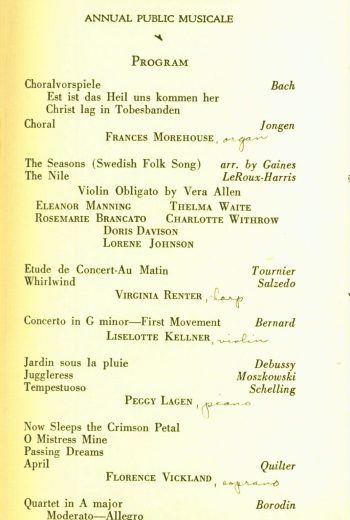

►April 1, 1950