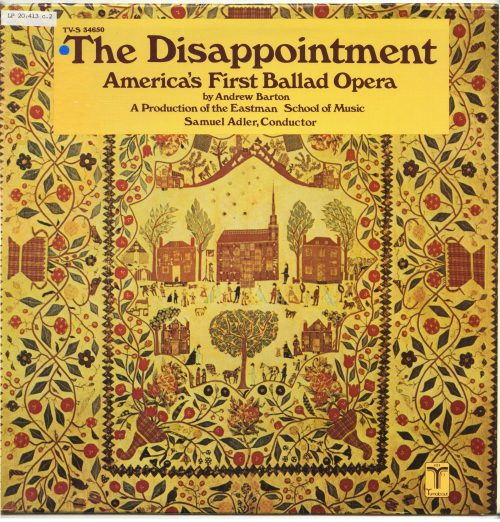

1976: Reconstruction of ballad opera The Disappointment (1767)

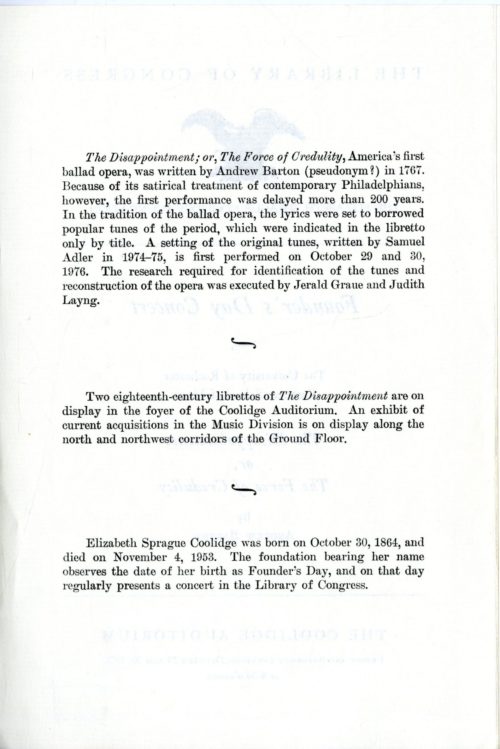

Throughout the year 1976, the USA observed its Bicentennial with a great deal of pomp, pride, and patriotic fervor. Those who are old enough to remember that time will no doubt still recall such iconic spectacles as the stunning armada of tall ships sailing into Boston Harbor. From the mother country, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip journeyed across the Atlantic to pay a state visit to the former colonies. On July 4th, the synchronized ringing of bells everywhere across the land resounded in a jubilant national chorus. In the performing arts, 1976 was a year of events and performances, both musical and dramatic, that evoked and celebrated Americana of the past while looking ahead expectantly to a bright future. As one reviewer so eloquently put it that fall, “We are nearing the end of a year specially marked by acts of archaeological piety in the arts.”[1] Here at the Eastman School of Music, there were numerous performances in recognition of the nation’s 200th birthday. These included a series of Bicentennial programs of chamber music at the Memorial Art Gallery; a concert of American choral music by the Eastman Chorale and the Chapel Choir; a patriotic-themed PRISM U.S.A. concert in the Eastman Theater; and the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s recording Homespun America, a collection of music for the Manchester (New Hampshire) Brass Band (ca. 1854-1858) that was commercially released by Vox Turnabout.[2] Elsewhere in Rochester, the “Opera under the Stars” series at Highland Park included one self-consciously American opera, none other than Howard Hanson’s Merry Mount.[3] Towards the end of the year, one of the Eastman School’s final Bicentennial gestures was the production of a 1767 ballad opera, The Disappointment: or, The Force of Credulity by Andrew Barton[4], regarded by music historians as having been the first native ballad opera in the American colonies.

Throughout the year 1976, the USA observed its Bicentennial with a great deal of pomp, pride, and patriotic fervor. Those who are old enough to remember that time will no doubt still recall such iconic spectacles as the stunning armada of tall ships sailing into Boston Harbor. From the mother country, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip journeyed across the Atlantic to pay a state visit to the former colonies. On July 4th, the synchronized ringing of bells everywhere across the land resounded in a jubilant national chorus. In the performing arts, 1976 was a year of events and performances, both musical and dramatic, that evoked and celebrated Americana of the past while looking ahead expectantly to a bright future. As one reviewer so eloquently put it that fall, “We are nearing the end of a year specially marked by acts of archaeological piety in the arts.”[1] Here at the Eastman School of Music, there were numerous performances in recognition of the nation’s 200th birthday. These included a series of Bicentennial programs of chamber music at the Memorial Art Gallery; a concert of American choral music by the Eastman Chorale and the Chapel Choir; a patriotic-themed PRISM U.S.A. concert in the Eastman Theater; and the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s recording Homespun America, a collection of music for the Manchester (New Hampshire) Brass Band (ca. 1854-1858) that was commercially released by Vox Turnabout.[2] Elsewhere in Rochester, the “Opera under the Stars” series at Highland Park included one self-consciously American opera, none other than Howard Hanson’s Merry Mount.[3] Towards the end of the year, one of the Eastman School’s final Bicentennial gestures was the production of a 1767 ballad opera, The Disappointment: or, The Force of Credulity by Andrew Barton[4], regarded by music historians as having been the first native ballad opera in the American colonies.

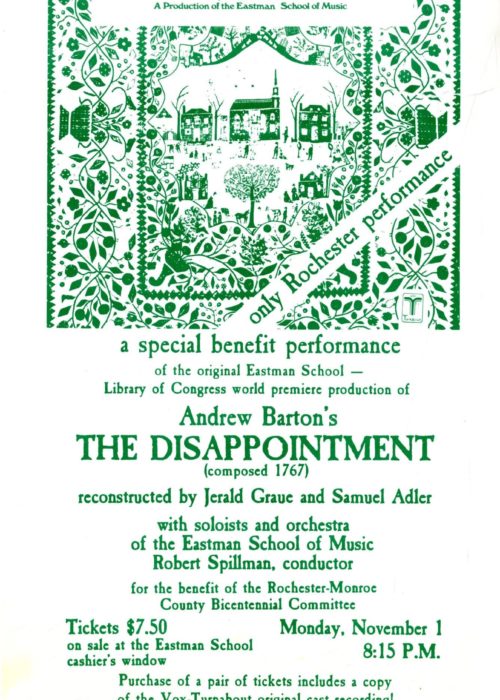

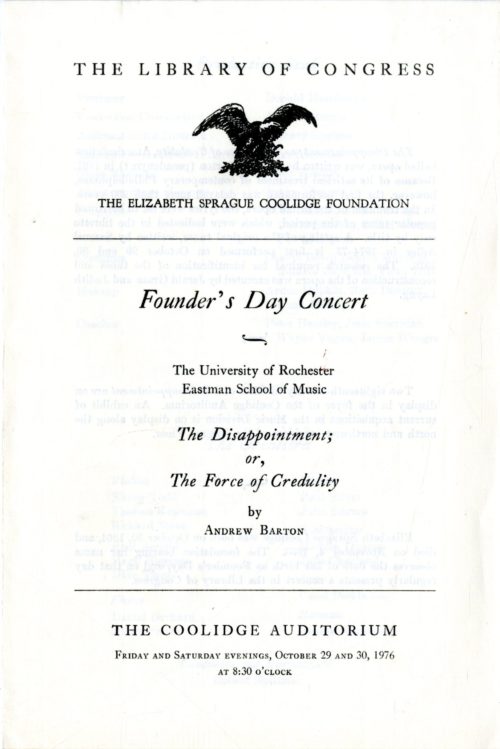

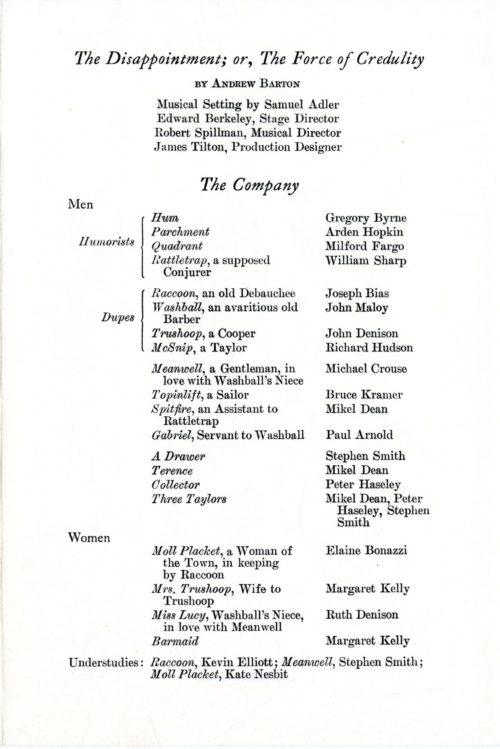

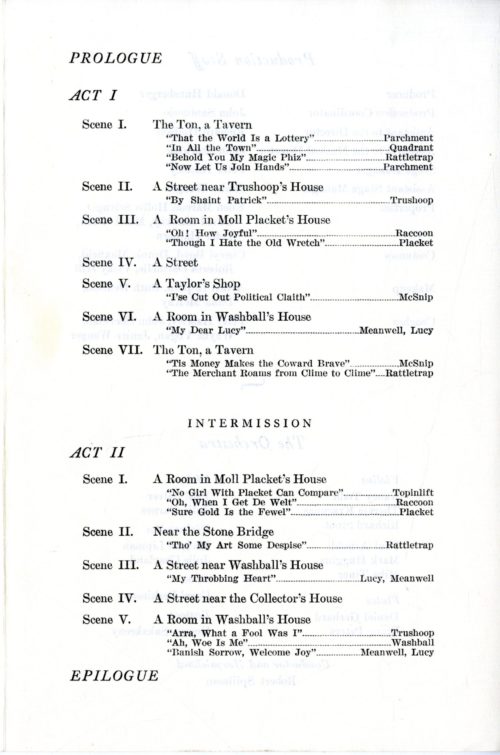

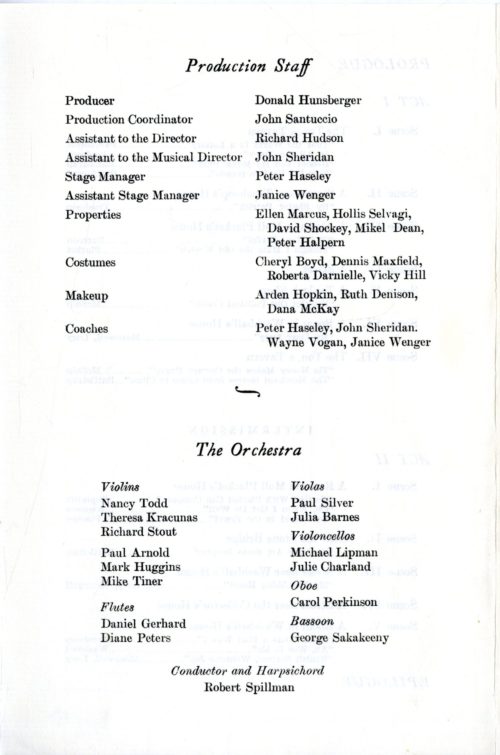

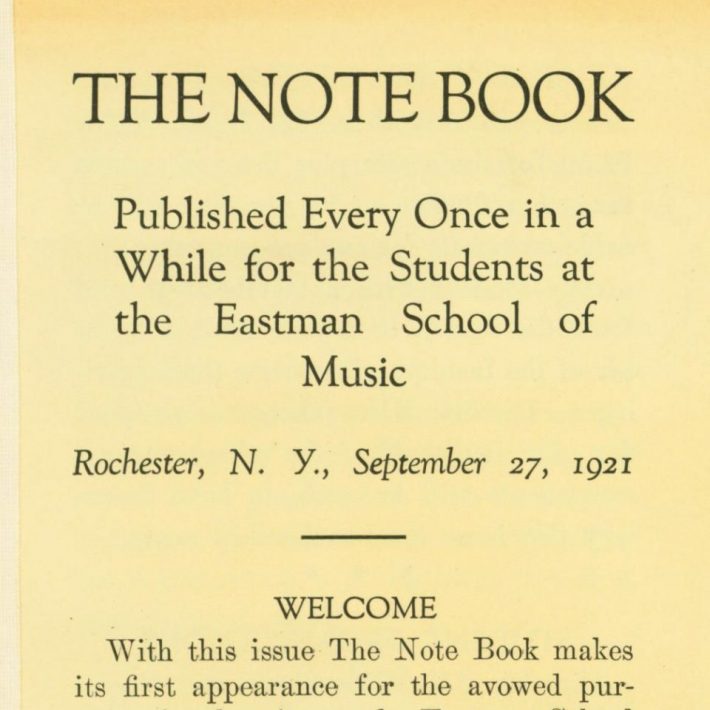

And so forty-six years ago this week, on October 29th and 30th, 1976, performing forces and an artistic team from the Eastman School mounted two performances of the newly reconstructed The Disappointment at the Coolidge Auditorium at the Library of Congress (printed program displayed here). Accompanying the performances was a display of two copies of the 1767 libretto in the auditorium’s foyer. The performances at the Library of Congress were followed by a performance in Kilbourn Hall on November 1st, which was a special benefit for the Rochester-Monroe County Bicentennial Committee. The cast was comprised of not quite two dozen Eastman School students and alumni, together with faculty members Milford Fargo[5] and John Maloy[6]. The cast also included internationally renowned mezzo soprano Elaine Bonazzi, BM ’51, for whom the production marked a return engagement at her alma mater.[7] The orchestra was comprised of 14 Eastman students, conducted from the harpsichord by Robert Spillman.

The history of the ballad opera genre has been thoroughly researched and documented. For purposes of this sketch, suffice it to say that a ballad opera resembled a musical theater piece, having musical numbers alternating with dialogue; its dramatic content was usually comic in tone, and the musical numbers had been sourced from traditional (or otherwise familiar and in vogue) melodies. In the English ballad opera tradition, The Beggar’s Opera (1728) by John Gay represented the earliest successful ballad opera, and one that has remained in the repertory.[8] In colonial North America, the first documented production of a ballad opera took place in 1735, and several English ballad operas were performed in the North American colonies in subsequent years. However, notwithstanding its lack of a premiere performance, The Disappointment: or, The Force of Credulity is today regarded as having been North America’s first native ballad opera. In early 1767 the Philadelphia Gazette announced that The Disappointment was set to open at Philadelphia’s newly built Southwark Theater on April 20, 1767, but four days before the opening was to have taken place, the performance was abruptly cancelled as being “unfit for the stage.”[9] On scrutiny, the work was seen to contain some unflattering “reflections” of some real-life Philadelphians, who in the story become the unwitting and embarrassed objects of a prank.

There is no record of any performance of The Disappointment having taken place either in 1767 or later, but the libretto was nevertheless published (New York, 1767), with its title page promoting the work as “a new American comic-opera of two acts.” In the preface, the author sketched out his reasons for writing the work; he had been sharing the story informally with his friends, who had encouraged him (characterized by the author as a “torrent of solicitations from all quarters”) to write it down, and he had eventually capitulated to their requests. (Interestingly, the author cited as two of his several reasons “the infrequency of dramatic compositions in America” and “the necessity of contributing to the entertainment of the city (i.e. Philadelphia)”.) The action follows the exploits and antics which result when four so-called Humorists—by name, Hum, Parchment, Quadrant, and Rattletrap—devise a scheme to trick four other characters, the so-called Dupes—by name, Washball, Raccoon, Trushoop, and McSnip— to search for treasure supposedly buried by Blackbeard and his pirates. It should go without saying that the scheme is manifestly intended to embarrass and defame the Dupes in their pursuit of the buried treasure. Thus, this comic piece turns out to constitute something of a morality play; indeed, two lines in the Prologue to Act I confirm as much: “Theatric-bus’ness was, and still shou’d be,/To point out vice in its deformity”. And as the author further expounded in the Preface:

The moral shews the folly of an over credulity and desire of money, and how apt men are (especially old men) to be unwarily drawn into schemes where there is but the least shadow of gain; and concludes with these observations, that mankind ought to be contented with their respective stations; to follow their vocations with honesty and industry–the only sure way to gain riches.[10]

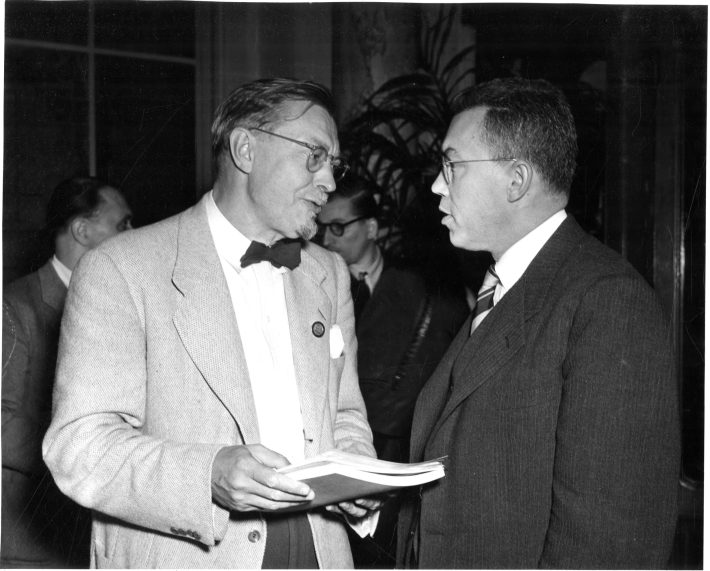

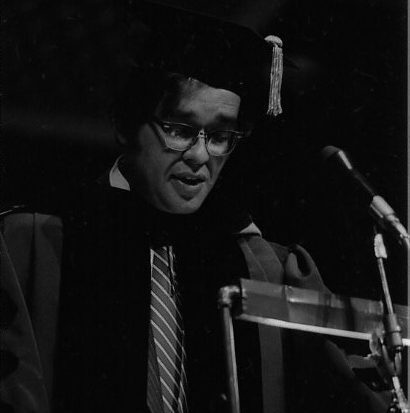

Fast forward to the 1970s. Fully two centuries after the cancelled premiere, new interest resulted in a reconstruction and a staging of The Disappointment. At the Eastman School of Music, Samuel Adler[11] made settings of the original melodies and also composed an overture and new incidental music. The reconstruction was supported by research undertaken by musicologists Jerald Graue[12] and Judith C. Layng[13] whose work was informed by the dual obligations to preserve the flavor and the intimacy of the work’s 18th-century origins, and to ensure that the reconstructed work would be theatrically effective and viable for modern audiences. Their research included identifying the original tune sources, and the reconstruction’s new settings and newly composed music were all informed by 18th-century idioms. Musically, the work was comprised of an opening song, eighteen vocal numbers (called “airs” in the score), and an epilogue of two vocal numbers. The Adler-Graue-Layng reconstruction and the staging by Eastman forces were subsequently given permanent form by means of publication and recording. The reconstructed manifestation of The Disappointment was published—in both full score and vocal score—by A-R Editions (c1976) in that publisher’s series Recent Researches in American Music, edited by musicologists Graue and Layng. (The Sibley Music Library holds a copy under call no. M2 .R2947A vols. 3-4.) In the publication, the printed music is accompanied by scholarly discussion of the play and its origins, the problem of authorship, the challenges of the musical reconstruction, matters of performance practice, and still other aspects of the reconstruction. The sources of the 18 musical numbers (called “airs” in the score) are also identified; among them, modern American audiences will readily identify no. 4 as “Yankee Doodle”. Further, the work of the Eastman performing forces was captured in an LP recording that was issued by Vox Turnabout.[14] (The Sibley Music Library holds copies under call nos. LP 20, 412 and LP 20, 413.)

Once again the Eastman School had distinguished in the promotion of American music, this time in the operatic realm. Whereas Eastman Opera had previously staged numerous American operas (including student operas), the 1976 production of The Disappointment went further in that it engaged scholarly inquiry and research, as well as musical reconstruction informed by that research. It should further be noted that production of The Disappointment did not supplant the usual fall semester operatic production, for later in November, Eastman Opera student performers mounted a production of Richard Strauss’ Capriccio, directed by Frederic O’Brady.

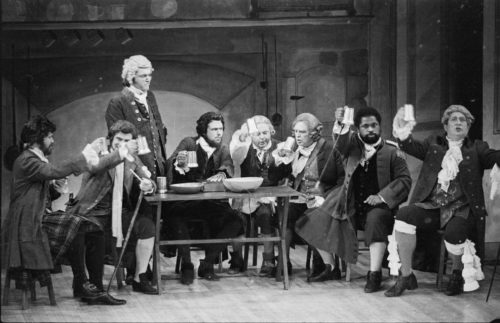

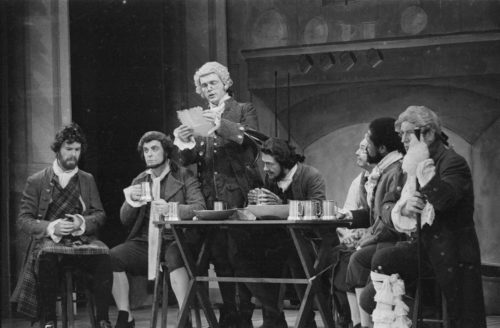

► photos (Louis Ouzer Archive). Master negative nos. R2248 : R2252

Note that Mr. Ouzer photographed the proceedings on October 24th, 1976.

► In the tavern in act I. The eight men on-stage are Parchment (standing), Raccoon (second from right), Washball (far right), and the rest, in no particular order, are Jack Rattletrap, Quadrant, Hum, Trushoop, and McSnip. Parchment, Hum, Quadrant, and Rattletrap are the four so-called Humorists who devise a cunning trap b which to exploit others for gain. Photo by Louis Ouzer.

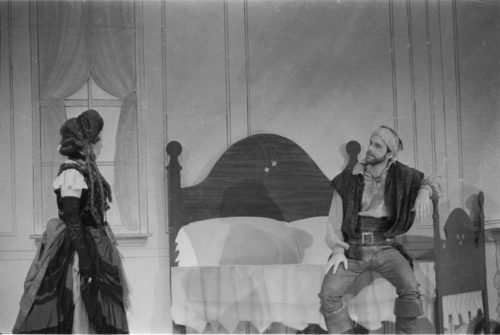

► Moll Placket with Topinlift, a sailor who is her boyfriend on the side, and for whom she intends to abandon Raccoon. Photos by Louis Ouzer.

[1] “Barton’s opera opens after a 209-year wait” by Joseph McLellan. Originally printed in The Washington Post and reprinted in The Rochester Times-Union, October 30, 1976. Preserved in Rochester Scrapbook October-November 1976, page 105. Sibley Music Library.

[2] Further, the Eastman School’s annual Arrangers Laboratory-Institute in 1976 included a patriotic-themed item in the annual Arrangers’ Holiday concert, which was a dramatic piece ”U.S.A. All the Way — a Musical Guide to American History” scored by seven individuals, and with Donald Hunsberger as narrator. This following in the tradition in earlier Arrangers’ Holidays of featuring a comic-dramatic sketch.

[3] Further to Merry Mount, Eastman Opera’s 1955 production of this opera was featured in “This Week at Eastman” in the entry for week of May 16th-22nd, 2022.

[4] Andrew Barton was most likely a pseudonym.

[5] Professor of Music Education; served from 1957 until his death in 1986.

[6] Professor of Voice; served from 1966 until his retirement in 2005.

[7] Elaine Bonazzi (1929-2019) enjoyed a successful career on the operatic stage from the 1950s until the 1990s.

[8] Indeed, The Beggar’s Opera has been the basis for later works, including Kurt Weill’s Dreigroschenoper (Threepenny Opera) (1928).

[9] Article “Ballad opera in the United States” by Susan L. Porter, accessible at Oxford Music Online, accessed on October 18, 2022.

[10] The quotations in this paragraph all from The Author’s Preface, which is reprinted in the A-R Editions score of The Disappointment.

[11] Professor of Composition; served 1966-94; Emeritus thereafter.

[12] Professor of Musicology; served 1971-82.

[13] Ms. Layng would later serve as director of the Oberlin College Conservatory Opera Department (served in that capacity 1979-1996).

[14] It seems pertinent to mention that the Vox label had numerous Eastman School associations, manifest in recordings by faculty artists and ensembles.