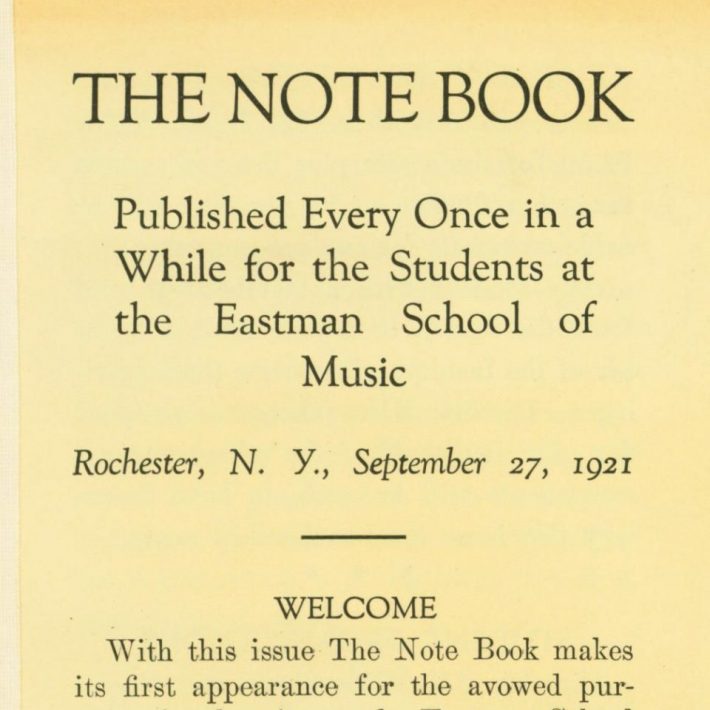

1956: “Painting with Sound” makes its debut on Rochester TV

Sixty-six years ago this week, on the evening of Saturday, October 13th, 1956, a television series featuring Eastman School musicians made its debut on station WROC-TV (channel 5) in Rochester. Sponsored by Rochester Gas & Electric Corporation (RG&E) in co-operation with the University of Rochester, the series Painting with Sound was a public service, essentially a music education course for the general viewing public. Altogether, the series was comprised of eleven half-hour programs that were broadcast on alternate Saturday evenings in the 7 PM/7:30 PM time slot, alternating week by week with another public service program, Court of Public Opinion moderated by local attorney and businessman Sol M. Linowitz.[1] Like so much televised content in the 1950s, Painting with Sound was broadcast live—or, if you prefer, in real time.[2] Just as in the theater or concert hall, the viewer saw and heard everything as it occurred and in the moment; there was no opportunity to edit or remove any misstatements, missed cues, or wrong notes.

► Ad for the series “Painting with Sound” (WROC-TV), printed in the Rochester Civic Music News, a weekly publication. Eastman School of Music Archives.

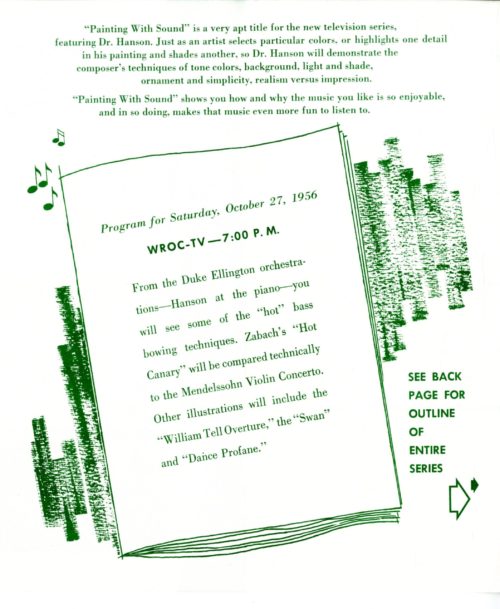

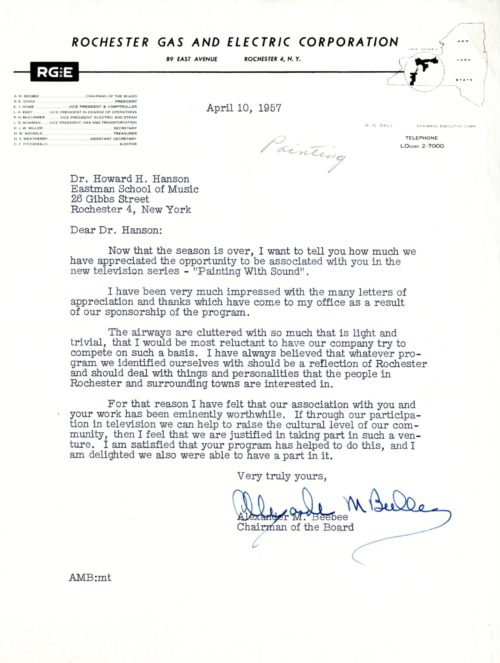

► RG&E’s extensive publicity campaign for Painting with Sound included distribution of printed materials such as this leaflet. The campaign also included mailings each week when a program would be broadcast to profile that week’s upcoming program. In addition, there were weekly ads in the area’s newspapers, including Rochester’s two dailies, the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle and the Rochester Times-Union. Howard Hanson Collection.

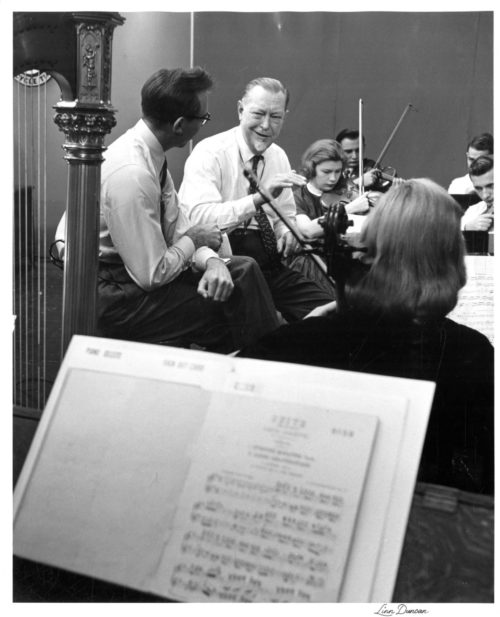

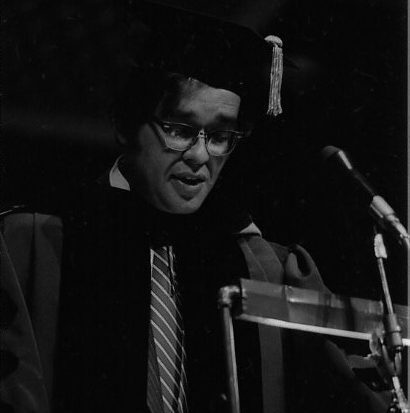

The series’ central figure was Howard Hanson, and here he was truly at his best, speaking in his various capacities as educator and composer and conductor while expounding on music of the orchestra, the medium of performance that he championed most ardently. In each Painting with Sound program Hanson concentrated on a particular piece of music, pointing out how the composer had put it all together, using the analogy of painting to illustrate how a piece of symphonic music was comprised of brush-strokes and other painterly gestures in sound. Together with him on the set were the musicians, who assisted Hanson by playing their assigned parts when cued; after Hanson had concluded his verbal explication, he conducted the orchestra in a complete rendition of the piece. In the pilot broadcast, the Eastman School Chamber Symphony was the ensemble of choice, a 32-piece orchestra that had been chosen expressly because the studio set would accommodate it (whereas the set would not accommodate a full-size symphony orchestra).

As the series continued, other Eastman School musicians were featured, such as the Eastman String Quartet;[3] on those evenings when any other complete ensemble happened to be on the set, that ensemble would oblige with a rendition of the featured work in its entirety following Hanson’s spoken presentation.

In the pilot episode, the Eastman School Chamber Symphony performed Anatoly Liadov’s tone poem The Enchanted Lake, a work that Hanson had conducted numerous times, and which he would conduct during the Eastman Philharmonia’s extensive 1961-62 tour. The draft script of the pilot program is presented here; among Hanson’s own papers, this the only extant script from the series. Note that the program opened with a bona fide conversation between Hanson and Don Lyon, the University of Rochester’s Director of Television and Radio, who would remain a regular presence in the series. The opening conversation introduces the characters and the plot, so to speak, and allows Hanson the moment to tell his rationale behind the series. The draft script then takes us point by point through Hanson’s explication of the composer’s work of composing and orchestrating the featured composition. Admittedly, some of the dialogue might seem dated or unusual to us now, such as the two speakers’ habit of repeatedly addressing one another by name (“Well, Don …” and “Well, Dr. Hanson…”), but perhaps some of that can be attributed to the reality that in 1956, the medium of television was still so new.

While Howard Hanson had made several television appearances before this series, they had been isolated occasions, whereas Painting with Sound was his first—and also the Eastman School’s first—dedicated television series. Coming at a time when network television was still so new, Painting with Sound was an appealing series that showcased the Eastman School’s talent and simultaneously provided quality viewing for the Rochester audience. Moreover, Howard Hanson’s archived correspondence confirms that there was an immediate and sustained response by the community, an outpouring of gratitude and appreciation manifest in letters and notes of appreciation sent by viewers. The letters came from private citizens, educators (teachers and administrators alike), and owners or other representatives of local businesses; they were variously addressed to Dr. Hanson or to RG&E (typically to the attention of Mr. Schuyler Baldwin, the company’s Director of Public Relations). The letters confirm some definite conclusions. Local viewers appreciated being served up classical music without being condescended to; they perceived that the series was on a higher level than what they had been accustomed to seeing on television, namely soap operas and the like, and they welcomed this; and they also saw in Hanson a man who represented a cultural asset in their community. One letter among Dr. Hanson’s papers was dated October 13th, written on the same evening as the pilot broadcast. In sharing her family’s enthusiasm for the program, the writer opined enthusiastically, “We should have more and larger doses of Dr. Hanson, then the Civic Music Association[4] wouldn’t have to worry about the future, because of the new generation of listeners he will have trained!”.

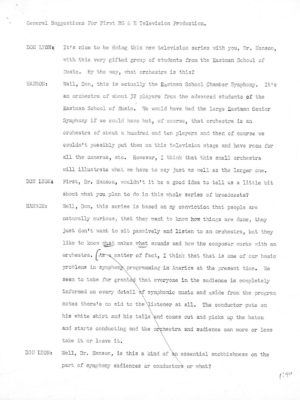

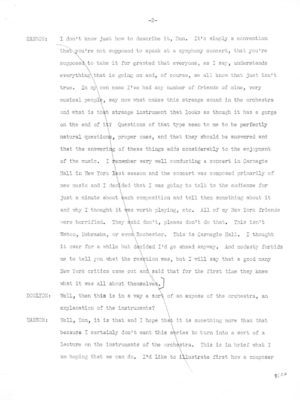

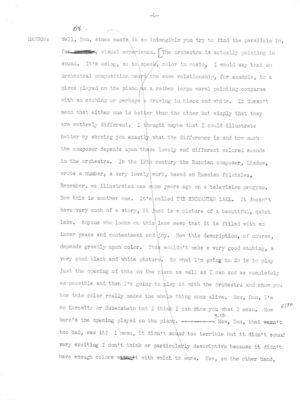

► Annotated draft script of the first program in the series Painting with Sound (WROC-TV). Note that the opening consisted of a dialogue eventually giving way to Hanson’s musical illustration, and finally an orchestral rendition of the featured composition in its entirety. Howard Hanson Collection.

More than one letter reflected enthusiasm over the series’ “non-stuffy” nature, such that Painting with Sound reflected an instance of “educational television” that did not require one to be a “long-hair” to understand and appreciate it.[5] One writer shared, “In my book this is ‘Educational Television’ of the non-stuffy variety, and renews my faith in the possibilities of the medium.” In other words, an experience of educational television that could actually be enjoyed (!). Perhaps one could actually overlook the word “educational,” as suggested by this viewer:

It would seem to us that this program should do a great deal that needs doing for music in Rochester. Dr. Hanson’s selections, presentation and especially his T.V. charm, make for a program that you need not be a so-called ‘long-hair’ to thoroughly enjoy. To us, it equals the similar work done by Leonard Bernstein on a national network presentation.

To be equally fair, we should also add that all of the programs we have seen, sponsored by your company have been enjoyable and informative. I’d prefer to skirt the word ‘educational’.

That last letter was one of several from viewers who compared Hanson’s TV persona with that of Leonard Bernstein, music director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and an emerging cultural superstar. Up to this time Maestro Bernstein had made numerous well-publicized television appearances, including on the series Omnibus.[6] A member of Hanson’s faculty at the Eastman School of Music echoed the Bernstein comparison in a note that he penned to Hanson immediately after the pilot program:

After viewing your telecast on Sat. Eve., all I can is “Who is this Second Bernstein?” and if N.B.C. or C.B.S. do not sign you and our wonderful youngsters they are crazy. You were really great.

And from another viewer:

Dr. Hanson, as always, is extremely interesting and has the faculty of making a program of this kind fascinating. The ability of the orchestra members, plus the capability and personality of Dr. Hanson combine to make this program really delightful.

One viewer wrote to Hanson describing his children’s response to Hanson’s on-screen performance:

Though my children are of the ‘Rock & Roll’ stage, they were all eyes and ears with an interest in every word you spoke and the movements you went through in conducting your musicians. Of course, the music possessed the quality that can be enjoyed by everyone who appreciates music by artists. We need more programs like yours to elevate the people’s musical appreciation.

There seemed to be a consensus, then, that Hanson had a talent for communicating. Such a talent could not help but further the cause of music (as well as that of television), as suggested in another letter to RG&E:

Dr. Hanson is wonderful at making things clear in his talks. It makes music much more meaningful, and I hope you will continue these programs. This is important in the job of making a larger audience for music. It must always be interesting and not childish or clichéd or dull, as so many TV things are.

Hanson had always relished his published speaking opportunities, but if the public’s response to Painting with Sound were any indication, the medium of television effectively put his presentation across. Moreover, the medium of network television was still so new as to offer viewers what seemed an intimate experience in their very own spaces. Whereas listening to the radio had engaged only the auditory senses, television offered the picture to accompany the sound, and now a viewer could experience the on-screen speaker being up close and in person:

I wish I could tell you how very much this house, of five adults, enjoyed Dr. Hanson’s presentation of Painting with Sound. To have such a famous musician come into our very own living-room in such an informal friendly way was delightful. But most of all, we appreciated the very beautiful music he and his young musicians brought to us. Thank you — to Dr. Hanson and to R.G.& E. for making his visit possible.

Not only was Howard Hanson an effective communicator, but the content itself was deemed worth watching. That viewpoint was reflected in letters from numerous viewers who perceived Painting with Sound to be on a higher level than other television fare. Those viewers conveyed their appreciation directly to RG&E, who was not only the series’ sponsor, but whose importance in their lives as the provider of their essential gas and electric services was keenly felt. One viewer—identifying herself as an employee of Strong Memorial Hospital—wrote the following:

I am so happy to see a musical program restoring the meaning and beauty of real music as opposed to that in the popular vein. May I urge you to continue to provide this type of program, and wish you much success throughout this present series, which we appreciate so much.

Echoing the same sentiment, one hopeful viewer took it a step further with a wish for more:

In these days of T.V.’s soap operas etc., programs of the type presented by your company are far too few. Perhaps some day we will be fortunate enough to have either the Philharmonic or Civic Orchestra presented on T.V.

And a vote of confidence from a decidedly satisfied customer:

During the last 30 years of being one of your ‘users’ and customers I have always held a great admiration for the magnificent service of your company, and have been most vocal on the subject. Now this fine and dignified method of your public relations (aside from the program itself) should join the admiration and thanks of every intelligent person in the city.

Still another letter on the same score is worth quoting at length:

Even though you had not asked for viewer reaction to the RG&E-sponsored program Painting with Sound, I would be compelled to send this letter. The program is so completely worthwhile and gratifying that it generates spontaneous reactions of appreciation and approval. (So you see, you generate something besides electricity.)

This program offers a musical experience that is so delightful and educational, the whole family can watch and listen with fascination and enjoyment. My wife and three children have joined me in seeing these programs and we are looking forward with pleasurable anticipation to future presentations.

The excellent musicianship of the performers, coupled with the authoritative — though informal and down-to-earth — comments of Dr. Howard Hanson, make these television appearances uniquely rewarding. In this respect, Dr. Hanson, with notable assistance from Don Lyon, provides a happy combination of ‘long-hair’ and ‘crew-cut’ that makes good music attractive and understandable to the layman.

And for yet another grateful RG&E customer, Howard Hanson was indisputably the star of the show:

For the second time I am constrained to convey to you my appreciation and approval of an R.G.&E. TV program. The Hanson series is simply a national TV-grade attraction. It would be a star number on a nation-wide hookup in my opinion.

Howard Hanson is really a very great man. He has everything. This down-to-earth approach to music could not have a more skilled and understanding exemplar. His development of the theme is not only good music (theory), but is fascinating to see and hear as pure entertainment.

Taking all of these letters into consideration, an overall impression emerges: viewers perceived in Painting with Sound an enjoyable and informing musical visit with Dr. Hanson, comfortably friendly and informal; Hanson the communicator, Hanson the avuncular visitor, Hanson the patient educator who didn’t make it feel educational at all. Rochester television viewers had not previously not seen anything of the kind, and they wanted more.

Interestingly, one viewer who wrote to Hanson just before Election Day (in a letter dated November 2nd, 1956) expressed her appreciation not only for Painting with Sound, but also for Hanson’s own partisan political activity on behalf of President Eisenhower’s re-election that season:

We were also most happy to have you speak out as you did for Our President, and the wisdom of keeping him in office. Your voice carries much weight because of your position, experience, and character, and I am most grateful that you have used it in President Eisenhower’s behalf. P.S. I refer to your letter published in The Rochester Times Union.[7]

He had become a public man in many respects, speaking out not only on behalf of music and the other creative and performing arts, but also in the political arena.

Finally, of the many viewers who reached out directly to Hanson, one letter stands out as perhaps the most touching of all, a particularly warm missive from a viewer who responded to the announcement of the series’ conclusion by addressing Hanson in these personal terms:

But you must realize also, our extreme gratitude to you; not only for this fine series of programs, but for the luster you have brought to our city; the talent you have molded and crystallized; and the fresh and rewarding understanding of music you have brought to all of us.

So many of (us) have watched your career from the beginning; from the first ‘American Composers’ concerts. Yet they did not half portend the magnificent future of the school and yourself. But now that the fame of both is secure, we are happy to boast, ‘I told you so!’ More than anything else, however, we are grateful for your presence among us. I know I speak for the entire city when I say we are so much richer for it.

We shall look forward to next week’s program; with pleasure for the music and the understanding of music it brings to us; with regret that it is the last for awhile. I pray you will be with us again very soon — and thank you.

As I mentioned earlier, Painting with Sound represented the first dedicated television series for both Howard Hanson and the Eastman School of Music. While the series represented a prime opportunity to bring the Eastman School’s high-caliber music-making into local living rooms, and to showcase the Eastman School’s many mighty talents, it’s clear that the endeavor had also marked a personal triumph for Howard Hanson. There would be more prime time television ahead before his retirement from the University of Rochester.

► Dr. Howard Hanson speaking with Mr. Don Lyon, Director of Television and Radio for the University of Rochester, on the set of Painting with Sound (WROC-TV). In two shots, members of the Eastman School Chamber Symphony are at the ready with their instruments; in the third shot, Hanson is conducting. Photos by Linn Duncan, Rochester, New York. Howard Hanson Collection.

_____________________________________________________________________________

[1] Sol M. Linowitz (1913-2005), Rochester-area attorney and businessman. He originated the public affairs TV program “Court of Public Opinion” which he also moderated; it ran for eight years (1951-59) on WROC-TV. Mr. Linowitz enjoyed an extensive career with Xerox Corporation and was ultimately named Chairman of the Board in 1960. He went on to serve as an advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter; in particular, he turned in distinguished diplomatic service during the Carter administration. President Clinton awarded him the President Medal of Freedom in 1998.

[2] One source states that whereas 80% of network television was broadcast live in 1953, by 1960 that percentage was down to 36%. “Television in the United States: The Late Golden Age” online at URL:

https://www.britannica.com/art/television-in-the-United-States/The-late-Golden-Age, accessed on 12 October 2022.

[3] The Eastman String Quartet was a faculty ensemble that would, in 1960, earn the distinction of being the Eastman School’s first ensemble to make an overseas tour. I featured the Eastman String Quartet in a previous entry of “This Week at Eastman: The View from the Archive” (week of May 9th-15th, 2021).

[4] The Rochester Civic Music Association (active 1930-75) was the body that governed the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, the Rochester Civic Orchestra, and other musical activities in the Greater Rochester area. It conducted annual fundraising drives to support these many endeavors. In 1975 it voted itself out of existence with the transition to the Rochester Philharmonic Association, Inc..

[5] The term “long-hair” is not so much in the lexicon today. According to one online dictionary, it means “an impractical intellectual” and also “a lover of fine arts”—which can include classical music. At one time, it was decidedly a term of mild derision.

[6] Most significantly, on the Sunday evening prior to the pilot broadcast of Painting with Sound, Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) had hosted the fifth season pilot of the series Omnibus; that pilot was a 90-minute show on the development of the American musical theater. Maestro Bernstein’s seven appearances on Omnibus have been commercially released on a DVD set by E1 Entertainment (c2010). Omnibus was a public affairs TV program (1952-61) created by the Ford Foundation to be an educational vehicle. It was hosted by English-born journalist and commentator Alistair Cooke (1908-2004) in his American television debut; many will remember the late Mr. Cooke as longtime host of the PBS series Masterpiece Theater.

[7] The writer was apparently referring to Hanson’s letter to the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, which was printed under the caption “Hanson Tells Why He’s for Ike” on October 1st, 1956. In that letter Hanson voiced his confidence in Eisenhower’s “ability to preserve the peace.” A staunch Republican, Hanson had joined the Citizens for Eisenhower Committee as a private citizen, but his correspondence confirms that his canvassing on behalf of President Eisenhower’s re-election had been conducted on his Eastman School time and using Eastman School letterhead.