Christopher Segall

Abstract

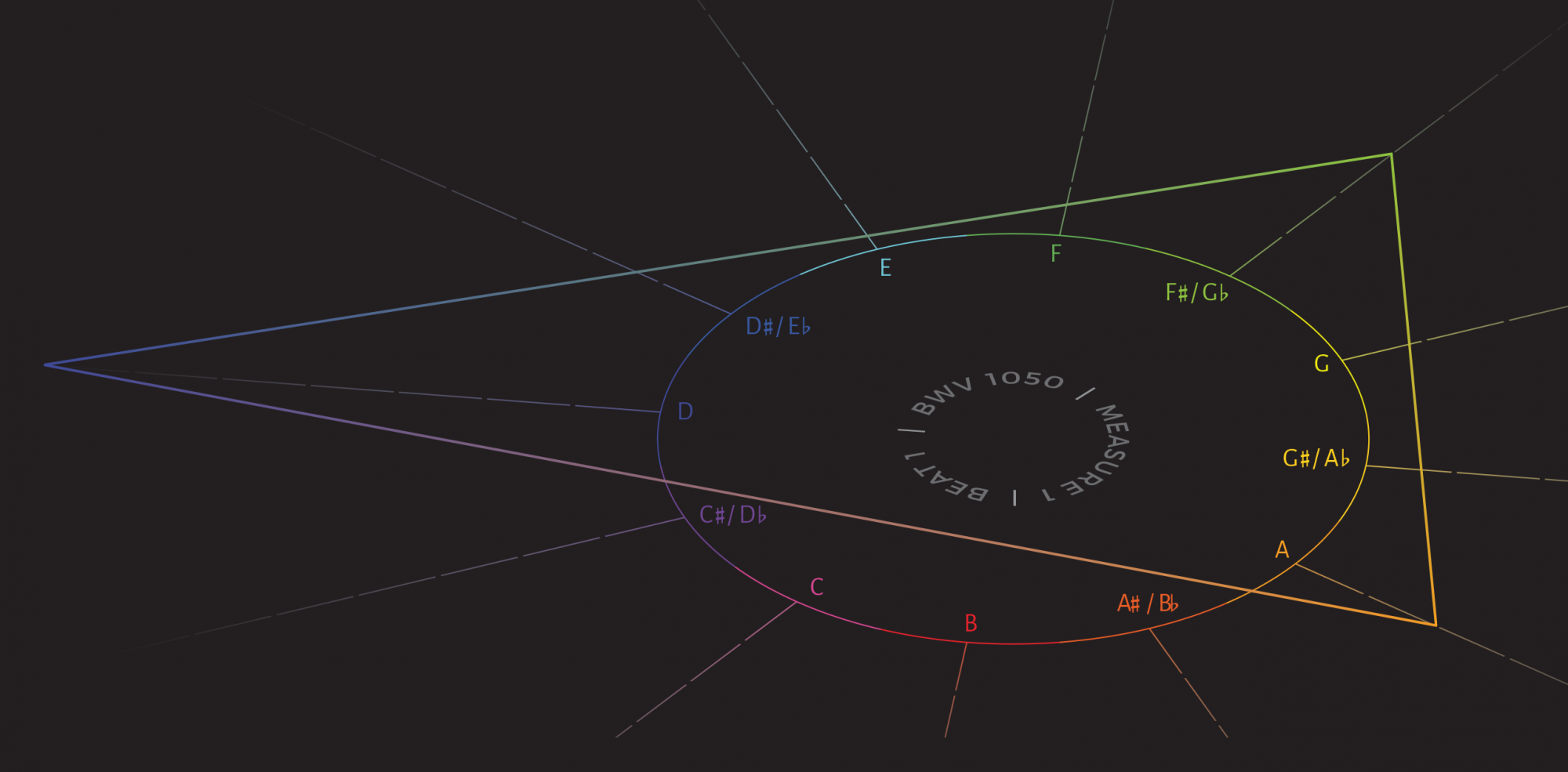

Scholars generally agree that Franz Liszt’s Bagatelle ohne Tonart (1885), “bagatelle without tonality” for piano, is locally tonal, but they do not agree on what the tonality is. English-language authors have proposed eight different tonal centers for the Bagatelle. Russian theorist Yuriy Kholopov adds a ninth: B minor. My analysis adopts Kholopov’s position and uses a harmonic reduction to demonstrate the viability of a B-minor hearing. I draw on Kholopov’s “states of tonality” to argue that different hearings of the Bagatelle depend on different conceptions of tonality and the variety of listening strategies they entail.

View PDF

Return to Volume 36

Keywords and Phrases: Franz Liszt, Bagatelle ohne Tonart, tonality, harmony, Romanticism, Yuriy Kholopov, Russian music theory, sostoyaniya tonal’nosti

Introduction

The late works of Franz Liszt are notorious for their adventuresome harmonic writing.1 The Bagatelle ohne Tonart (1885), “bagatelle without tonality” for piano, opens with a B–F tritone, employs liberal harmonic dissonance throughout, and avoids cadential confirmation of any key, ending instead with a tonally ambiguous diminished-seventh chord. David Carson Berry (2004), in a landmark study of the work, positions its tonal impulses within the domain of nineteenth-century Mehrdeutigkeit, “ambiguity” or “multiple meaning” (Saslaw 1990–91), thematized through the Bagatelle’s feints toward a kaleidoscopically shifting set of key centers. Despite the title’s hint of atonality (or proto-atonality), scholars generally agree that the work is locally tonal.

They do not agree, however, on what that tonality is. Surveying the English-language analytical literature, one encounters eight different tonal centers proposed for the Bagatelle. James Baker (2005) hears it in D, Harold Thompson (1974) in F. Sang-Hee Lym (1999) hears two tonal centers, C and F$$\sharp$$, whereas Federico Garcia (2006) hears three, C and F$$\sharp$$, plus A$$\flat$$. David Carson Berry hears five tonal centers vying for prominence over the course of the work: C, F$$\sharp$$, D, G, and A. In his persuasive estimation, individual harmonies point centripetally to unrealized local tonics. The work is “without tonality” in the sense of without a single tonality. Still other analysts avoid identifying tonal centers entirely. Robert Morgan (1976) hears the final diminished-seventh chord, G$$\sharp$$–B–D–F, as the work’s tonic sonority, a dissonant structure prolonged from the beginning of the piece. Perhaps wisely, Bernard Lemoine (1981, 130) equivocates, leaving the choice of tonal center to “subjective judgment.”2

To these eight tonal centers, the Russian-language literature adds a ninth. Yuriy Kholopov’s harmony treatise, Garmoniya, refers to the work with a provocative parenthesis as the “Bagatelle ohne Tonart (in B minor)” (2003, 416). Although Kholopov does not offer an analysis, he adumbrates his proposition elsewhere, writing that the Bagatelle is “clearly in B minor” and that it ends not with tonal resolution, but rather with “that favorite device of the Romantics, a deceptive cadence” (1980, 37).3 Kholopov’s confident B-minor assignation betrays no hint of potential debate, such as is found among English-language writings.4

In the present analysis, I adopt Kholopov’s position and argue that the Bagatelle ohne Tonart can be heard in the key of B minor. I use a harmonic reduction of the complete work to demonstrate the viability of a B-minor hearing. In offering a new hearing of a much-analyzed work, I do not wish to call the prior analyses into question. I acknowledge that the Bagatelle accommodates a variety of tonal listening strategies, each strategy giving rise to a different interpretation of the work’s tonal center. I conclude by returning to Kholopov and his notion of “states of tonality” to argue that each strategy depends on a different conception of a tonality that was in flux in the late nineteenth century.

1. B Minor

Three factors obscure a B-minor interpretation of the Bagatelle:

- There is no key signature.

- Scale-degree $$\sharp\hat4$$, E$$\sharp$$, is spelled enharmonically as F$$\natural$$ throughout.

- The work ends in the middle of a cadential progression, on a functional vii\dim7/V harmony.

The first two factors concern the work’s notation. It would certainly appear contradictory for a work entitled Bagatelle ohne Tonart to exhibit a 2$$\sharp$$ (or any other) key signature. The blank key signature reinforces the idea that the work is “without tonality.” A functional E$$\sharp$$, that is, $$\sharp\hat4$$ tending upward to $$\hat5$$, is consistently rendered as F$$\natural$$. A B-minor interpretation compels performers and listeners to experience F$$\natural$$ appoggiaturas as counteracting or overcoming their notated tendency when they push upward to F$$\sharp$$.

The third factor is most important. I contend that, in a B-minor hearing, the work ends in the middle of a functional cadential progression that is left incomplete. The final harmony expresses dominant-of-the-dominant function; rather than proceeding to dominant and tonic, it reverberates unresolved at the piece’s close, a Romantic fragment. Kholopov writes of a deceptive cadence here, and although the cadential process is indeed interrupted, I diverge from Kholopov in arguing that the work ends before any cadence has taken place.5

Theories of formal function describe how some phrases can begin “already in the middle.” Whereas typical themes begin with an initial formal function, most commonly supported harmonically with tonic prolongation, some themes bypass their putative “beginnings” entirely, starting directly with a medial or final function marked by melodic fragmentation, off-tonic harmony, or a sequential or cadential progression (Caplin 1998, 111–115). The Bagatelle engineers the complementary phenomenon. Rather than beginning in medias res, it ends while in progress. Its final diminished-seventh chord remains unresolved, engendering a feeling of unfulfilled desire or of expectation. Notably, this interpretation contrasts with Morgan’s view of the final diminished-seventh chord as a tonic. Morgan reads the final chord as a stable goal; the B-minor hearing interprets it as unstable, its goal chimerical.

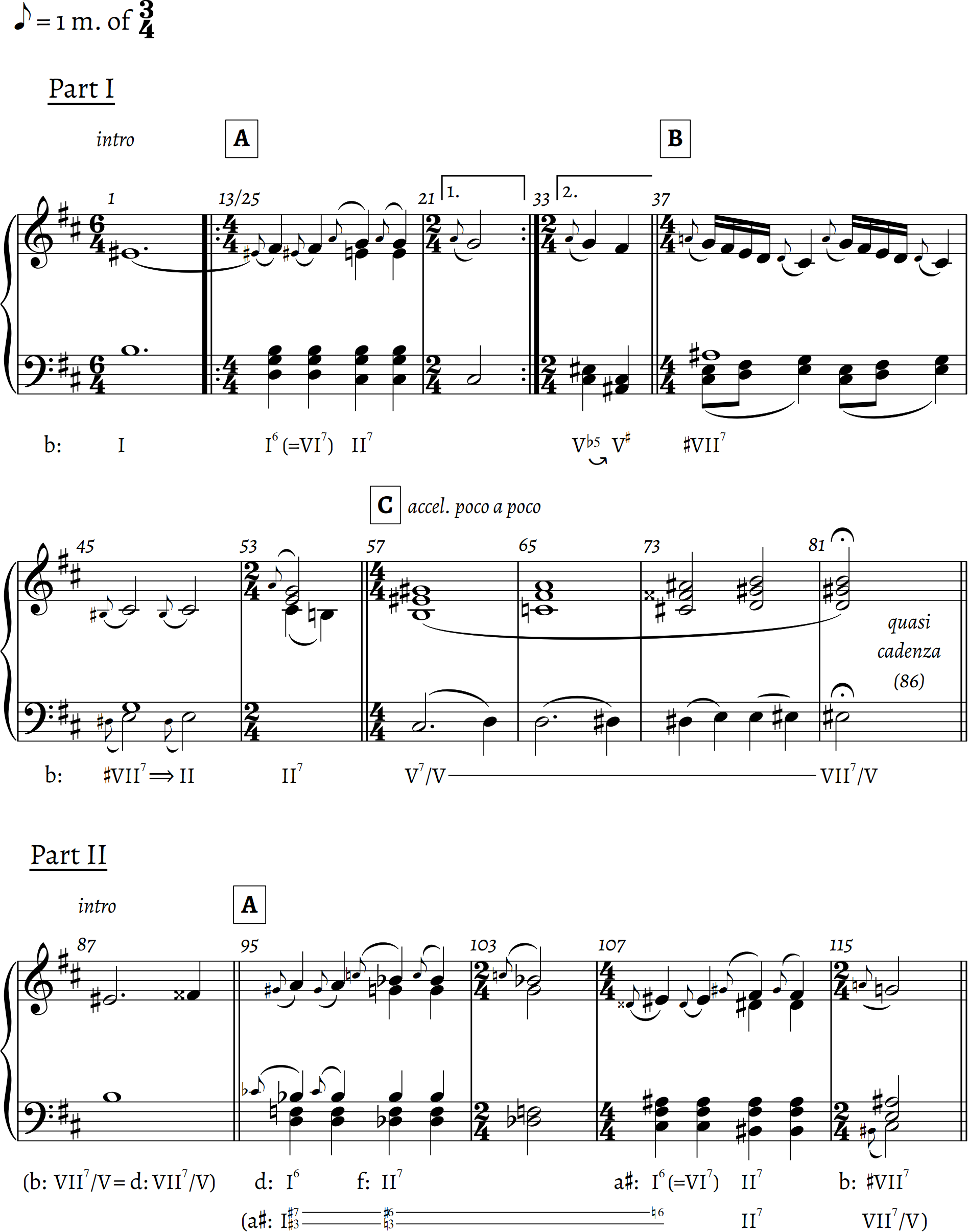

2. Overview: Form and Hypermeter

The Bagatelle consists of two halves, the second an embellished restatement of the first. Following Berry (2004, 232), I refer to the halves as Part I and Part II (Figure 1). Each part consists of a sentence-like structure loosened via numerous extensions and repetitions. The non-functional section letters A, B, and C correspond roughly to a basic idea, contrasting idea, and continuation, the last marked by sequencing and harmonic acceleration.6 A single harmonic phrase thus underlies each part, and this phrase, which ends on dominant-of-the-dominant function, is incomplete. The loose, incomplete formal-harmonic structure is a hallmark of the Bagatelle’s Romanticism.7

| Part I | Part II | ||

| 1 | intro | 87 | intro |

| 13 | A (b.i.) | 95 | A |

| 37 | B (c.i.) | 119 | B |

| 57 | C (cont.) | 149 | C |

| 86 | cadenza | 177 | cadenza |

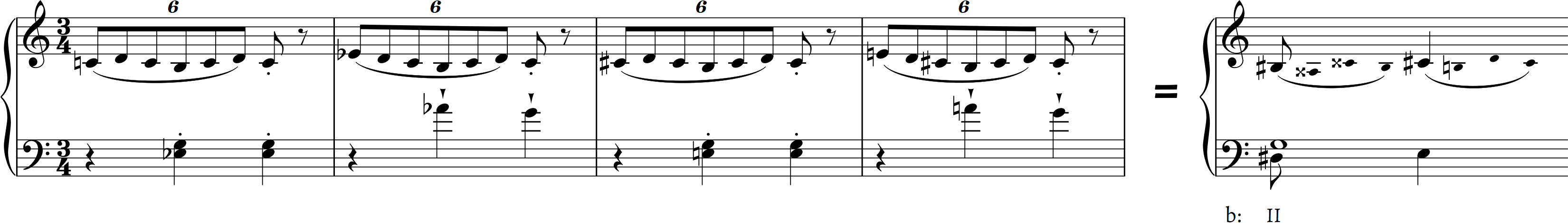

Equally characteristic of the Romantic era is the work’s regular hypermeter.8 The Bagatelle is notated in \time{3}{4} time at a fast tempo. Each pair of notated measures combines into a single experiential “\time{6}{4},” with the primary hyperbeats—quarter notes in the durational reduction of Example 1, below—occurring on odd-numbered downbeats. This coalesces cleanly into consistent four-measure duple hypermeter and eight-measure quadruple hypermeter.9

3. Durational Reduction

Example 1 is a durational reduction of the entire work. Quarter notes in the reduction represent two measures of \time{3}{4} (the experiential “\time{6}{4}”); the indicated measures are hypermeasures. A four-quarter hypermeasure in the reduction thus represents eight actual measures of the original score. I have simplified the harmony by removing most embellishing tones.

The durational reduction is meant to be played.10 Readers, that is, should play through the durational reduction at the keyboard, attending to the stipulated Roman numerals; they should proceed afterward to the complete work. I thus intend readers to train themselves to hear the Bagatelle in B minor and test my claim that a B-minor hearing is viable by listening to the Bagatelle as an elaboration of the reduction.

The durational reduction adds a two-sharp key signature to the score. Roman numerals are uppercase and follow the diatonic scale. Arabic numerals represent chord members above the root, not figured bass; inversions can be inferred from the musical notation but are not represented in the chord symbols. This system has two advantages for present purposes. First, it easily accommodates added-note chords. Thus, I6 in the A section symbolizes a tonic triad with added sixth (B–D–F$$\sharp$$–G), not a first-inversion tonic triad. (The chord does happen to appear in first inversion, but this is a coincidence and is not reflected by the numeral 6.) Second, it foregrounds voice-leading motion over changes in chord quality (e.g., I$$\sharp$$3–$$\natural$$3 instead of I–i in the A section of Part II) in passages where, my analysis argues, voice leading drives the progression.

Appoggiaturas, represented with small noteheads, resolve by step to chord tones. When playing the reduction at the keyboard, readers should play each appoggiatura directly on the

(hyper-)beat, occupying half the length of the chord tone to which it resolves. Appoggiaturas frequently sound one or two notated measures before the note of resolution.

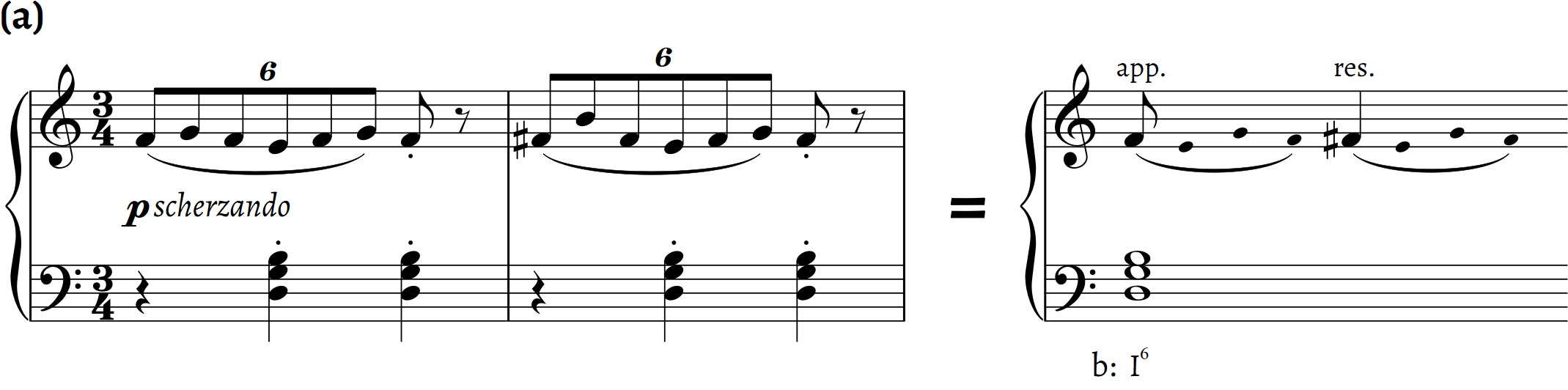

In the score, both appoggiaturas and chord tones are often decorated with local embellishments. The A section begins with an E$$\sharp$$ appoggiatura resolving to the F$$\sharp$$ of a I6 chord. The original score renders the E$$\sharp$$ enharmonically as F$$\natural$$ (Example 2a). Triplet double neighbors embellish both appoggiatura (m. 13) and chord tone (m. 14). The left hand maintains D–G–B across both measures, reinforcing the harmonic stasis that permits hearing E$$\sharp$$ as an appoggiatura, which lingers unresolved from the Bagatelle’s introduction (mm. 1–12), where it was introduced melodically. Had it been notated enharmonically as E$$\sharp$$, the double neighbors in m. 13 would have required double sharps (Example 2b). Liszt’s notation with F$$\natural$$ is easier to read and perform.11

Example 2. Franz Liszt, Bagatelle ohne Tonart, mm. 13–14.

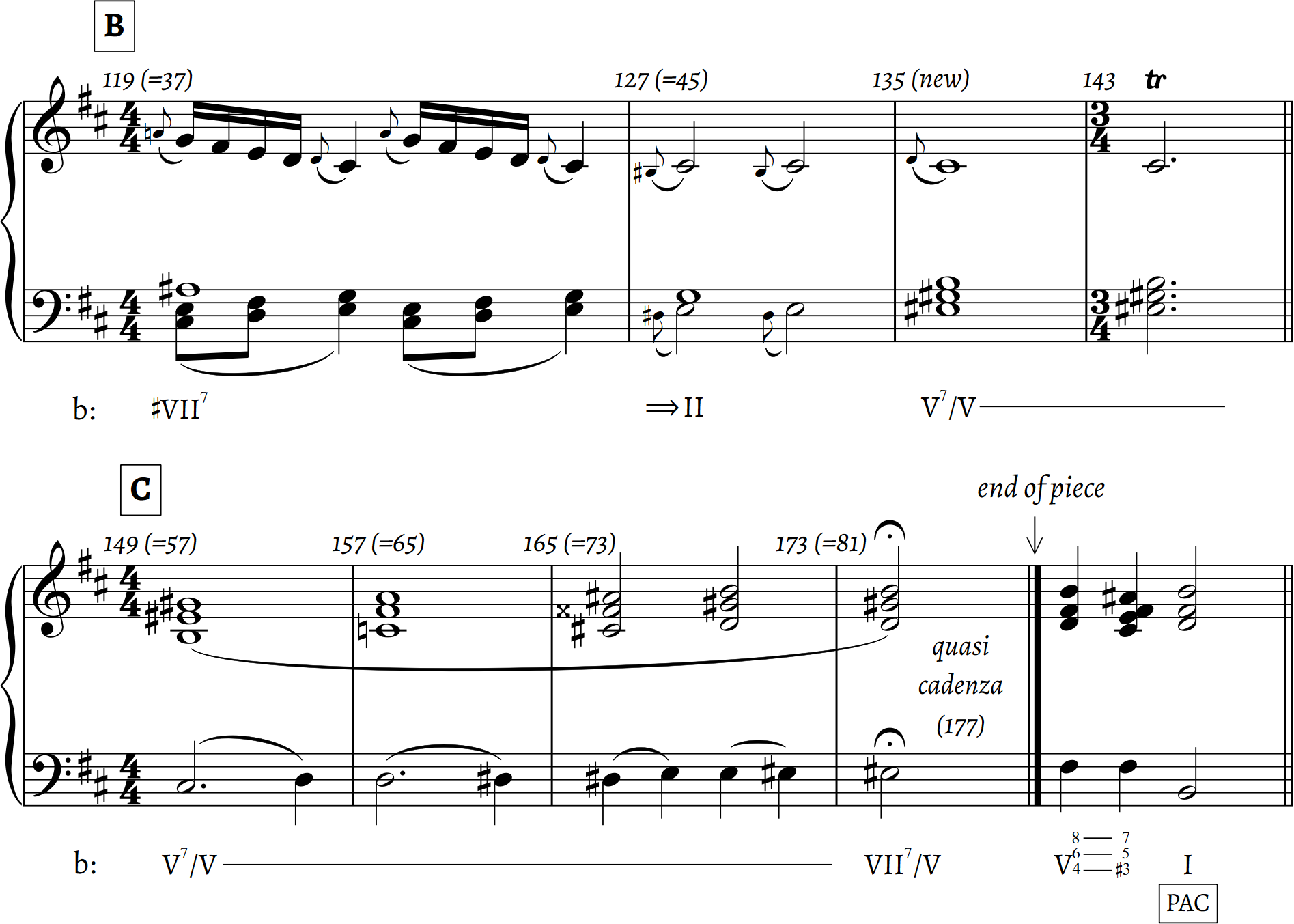

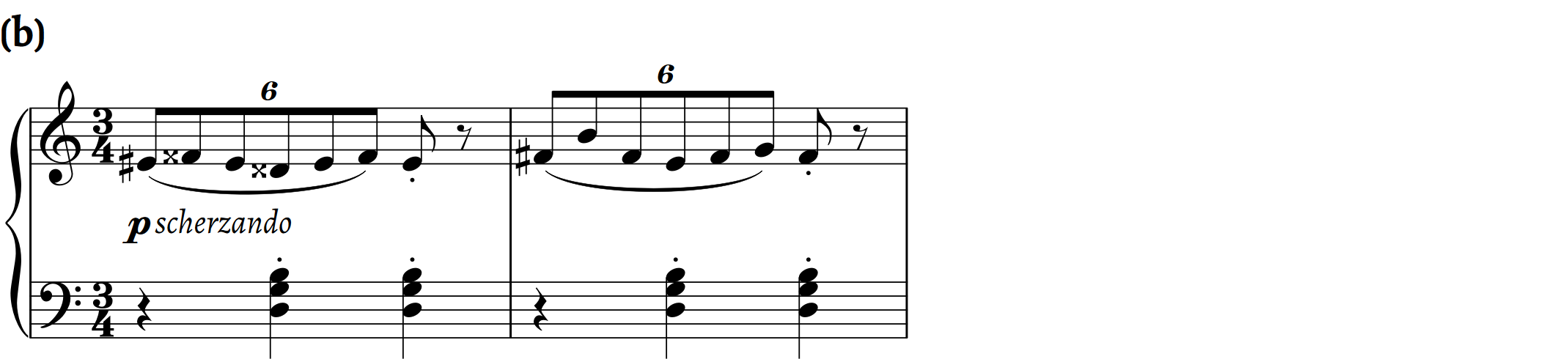

The single, incomplete harmonic progression that underlies Part I focuses predominantly on pre-dominant harmony. Tonic, with added sixth, insinuates itself only loosely in the A section. This initial I6 is equivalent, by way of Rameauian double emploi, to VI7, which impels a root motion by falling fifth to II7 (m. 17). The G in the tenor register is encircled by whole-tone double neighbors, while the right hand’s melody steps chromatically between alto-register chord-tone E and soprano-register appoggiatura A (Example 3). Only at measure 36, within the “second ending” of Example 1, does the music articulate the major dominant, in first inversion, to conclude the A section.

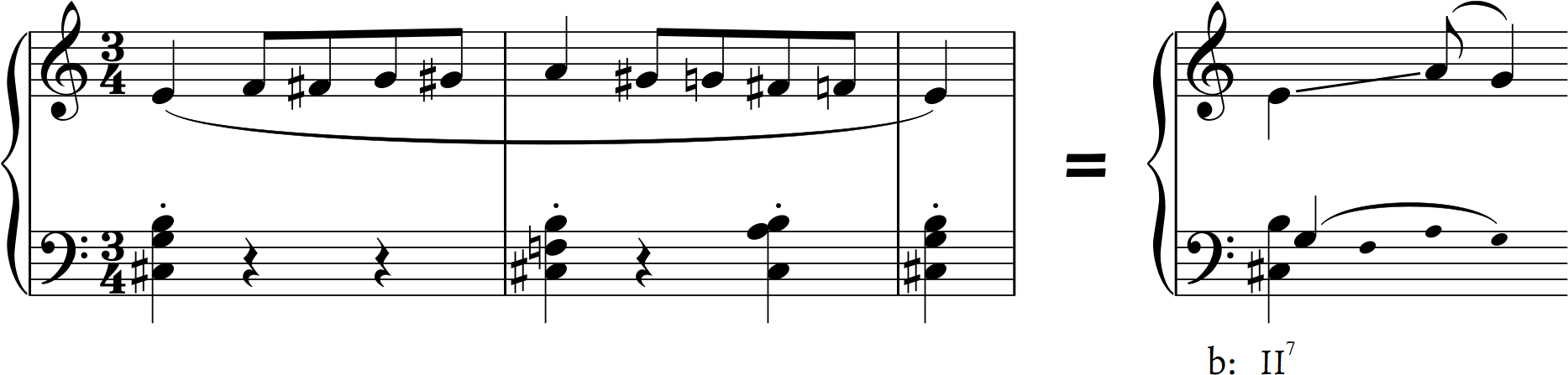

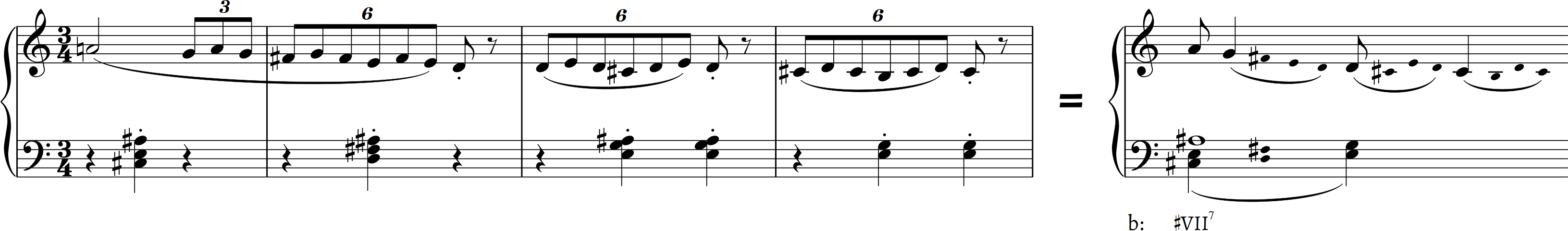

The B section expands a diminished-seventh harmony, $$\sharp$$VII7, which ultimately sheds its leading tone to re-attain II. The initial expansion of $$\sharp$$VII7 (m. 37) is effected via passing thirds in the bass, producing an apparent augmented triad on a hyper-offbeat (Example 4).12 It is during the following hypermeasure (m. 45) that A$$\sharp$$ is dropped, leaving a diminished II chord in first inversion. This harmony is embellished by two lower neighbors, D$$\sharp$$ and B$$\sharp$$, spelled enharmonically to produce an apparent C-minor triad (Example 5).

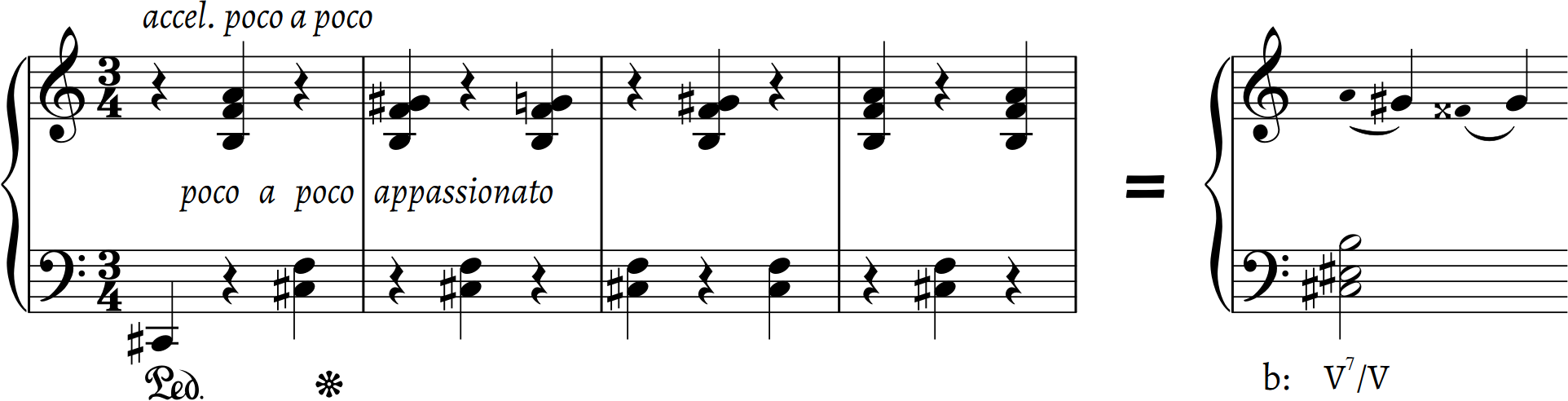

The C section is an accelerating harmonic sequence that expands V7/V into VII7/V. Double neighbors, once again, decorate the uppermost pitches (Example 6). Liszt’s enharmonic spellings stubbornly adhere to F$$\natural$$ over E$$\sharp$$, yielding notated diminished fourths (C$$\sharp$$–F, m. 57) and augmented seconds (F–G$$\sharp$$, m. 79) where major and minor thirds may have sufficed. The general trajectory, nonetheless, prolongs dominant-of-the-dominant function, ending with a cadenza-like flourish on an unstable VII7/V harmony (m. 86). No resolution to V or I occurs. The progression is shorn of its tonal goal, and Part I ends harmonically incomplete.

Part II traces the same harmonic path as Part I, now with new surface embellishments. There is a new extension at the end of the B section (mm. 135–148), which introduces the V7/V that initiates the C section. The most significant change is the transposition of three segments of the A section, each by a different interval. The hypermeasure at m. 95 is a transposition of that at m. 13, the first half up a minor third (from B minor to D minor), the second half up a diminished fifth (from B minor to F minor). The hypermeasure at m. 107 is a transposition of that at m. 25 down a minor second (from B minor to A$$\sharp$$ minor). The A section ends with a tonal course correction (m. 115) that reinstates $$\sharp$$VII7 of B minor.

As Example 1 suggests, the symmetry of the cadenza-flourish diminished-seventh chord abets the minor-third transposition. The final harmony of Part I, VII7/V in B minor, carries the same Roman numeral in D minor; it functions as a common-tone diminished-seventh chord when it discharges directly to tonic. Common-tone voice leading reigns throughout the remainder of the new A section. The four primary harmonies—I6 in D minor, II7 in F minor, and I6 and II7 in A$$\sharp$$ minor—all contain the pitch A$$\sharp$$/B$$\flat$$. Example 1 proposes hearing the first three of these harmonies as inflections of the A$$\sharp$$-minor tonic, proceeding thereafter to II7 and VII7/V in that key. The final diminished-seventh chord is also $$\sharp$$VII7 in B minor, permitting a pivot to an untransposed restatement of the B section (m. 119).

From this point forward, Part II corresponds measure-for-measure to Part I (except for the newly interpolated extension at m. 135, mentioned previously). The music cycles through the B and C sections. It eventually reaches a functional VII7/V harmony (m. 177) and ascends registrally, a climactic arpeggiation arriving in the final notated measure. And then the work ends. This chord of maximum tension hangs in the air. Resolution is withheld, potentially leaving performers and listeners to desire it. One could mentally supply the missing ending, concluding the cadential progression rather than leaving it off in the middle. My own hypothetical completion (Example 7) is designed to help readers hear the Bagatelle as being in B minor. As a sounding thought experiment, it should be played where the notated score runs out. I supply the absent dominant and tonic and bring closure through a perfect authentic cadence. The actual Bagatelle, of course, ends on a functional dominant-of-the-dominant, with the elusive closure to be experienced as an absence.

4. States of Tonality

I have argued for the viability of a B-minor hearing of the Bagatelle ohne Tonart through the use of a durational reduction of the piece. In this final section, I compare my proposed analysis with that of others’, suggesting that their differences result from different kinds of tonal listening strategies. To do this, I will return to Kholopov and invoke his concept of “states of tonality” (sostoyaniya tonal’nosti).13 It is in the chapter on states of tonality that we find Kholopov’s reference to the Bagatelle “in B minor.” Kholopov offers the states of tonality as strategies for composition, but I present a new perspective by considering them as strategies for listening.14

Tonality, Kholopov (2003, 409–425) argues, changed over time. The functional tonality of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is one type, or “state,” of tonality, but others emerged over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Each state is distinguished by a unique configuration of four indices: (1) center (tsentr) or the “central element” (tsentral’nïy element) of the tonal system; (2) tonic (tonika), the realization of the tonal center as a sounding object; (3) sonance (sonantnost’), the gravitational relationship of consonance and dissonance; and (4) functions (funktsii), the meaning of harmonies in relation to the tonic. Each index admits various possibilities; they combine to produce the states of tonality. Kholopov enumerates ten states, but he clarifies that the list is not exhaustive. A few states concern the argument here.

The state of “floating tonality” (paryashchaya tonal’nost’), alternatively called “atonicity” (atonikal’nost’), refers to the functional presence of an unambiguous tonal center, but without any articulation of the tonic chord. The concept intersects with the fluctuating tonality of Arnold Schoenberg, which Berry has explored in connection with the Bagatelle.15 Kholopov’s prime exemplar of floating tonality is the A section of Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana, op. 16, no. 4, which avoids its B$$\flat$$-major tonic and evades cadence through a modulation to the G minor of the B section. Listeners are unlikely to experience the passage as atonal, but it can be heard as atonic, with its tonic harmony missing. The music fails to achieve closure; it maintains tension, floating without landing, then drifting away. The Bagatelle ohne Tonart “in B minor” also falls under the category of “floating tonality.” I submit that several late piano works of Alexander Scriabin fall into this category. For instance, Scriabin’s “Enigma,” op. 52, no. 2 (1907), avoids its D$$\flat$$-major tonic entirely, ending with an arpeggiated dominant seventh having “floated off” (envolé as marked) into the ether, in a manner strongly redolent of the conclusion to Liszt’s Bagatelle.16

The states of tonality give rise to a range of compositional approaches, but I contend that they also invite a range of listening approaches, even to one and the same work. No piece of music announces its intended state. Listening to the Bagatelle under the paradigm of various states of tonality yields a variety of interpretations, and I argue that differences in tonal state account for the different analyses of the work. The category of “floating tonality” offers a model for hearing the Bagatelle in B minor with an incomplete harmonic progression, as Kholopov suggests. To amend a locution from Berry (2004, 246), it proposes ohne Tonart to mean “without the fulfillment of the tonic.”

But three other states of tonality have been brought to bear on hearing the Bagatelle. First, in “attenuated tonality” (snyataya tonal’nost’), each chord points to a given key or keys, but there is no single key overall. Berry, in hearing five tonal centers implied at various points in the work, takes this approach. He writes of the Bagatelle as a work “without the fulfillment of a tonic” (emphasis added), meaning any tonic. Second, in “ambiguous” or “multiple tonality” (mnogoznachnaya tonal’nost’), the harmonic progression is viable and determinate in two keys simultaneously; each chord can be interpreted functionally in both keys. Listening in this manner gives space for Lym’s and Garcia’s perception of dual tonal centers, C and F$$\sharp$$, both suggested at once by the opening B–F tritone. Third, “dissonant tonality” (dissonantnaya tonal’nost’) involves functional tonality with a dissonant tonic. Morgan’s prolongation of a tonic diminished-seventh chord follows the precepts of this “dissonant tonality.”

States of tonality are frameworks. They do not reside in the music; rather, they are imposed on the music. The concept of states of tonality makes explicit the frames of reference that allow divergent hearings and analyses to coexist. The Bagatelle ohne Tonart’s obscured tonal center, ambiguous enharmonic notation, and tantalizing title invite this multiplicity of approaches and orientations. My B-minor analysis is concordant with the interpretation of “floating tonality” suggested by Kholopov. I have argued that a B-minor hearing is viable, in which the work ends in the middle of a functional cadential progression, without resolution. In this sense, ohne Tonart can well be understood as “atonic.”

References

Baker, James M. 1983. “Schenkerian Analysis and Post-Tonal Music.” In Aspects of Schenkerian Theory, edited by David Beach, 153–186. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Baker, James M. 2005. “Liszt’s Late Piano Works: A Survey.” In The Cambridge Companion to Liszt, edited by Kenneth Hamilton, 86–119. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bakulina, Ellen. 2015a. “Tonality and Mutability in Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil, Movement 12.” Journal of Music Theory 59/1: 63–97.

Bakulina, Ellen. 2015b. “Yuri Kholopov’s ‘States of Tonality’ (sostoianiia tonal’nosti).” Presented at the annual meeting of the Russian Music Theory Interest Group, Society for Music Theory, St. Louis, MO, 31 October.

Berry, David Carson. 2004. “The Meaning(s) of ‘Without’: An Exploration of Liszt’s Bagatelle ohne Tonart.” 19th-Century Music 27/3: 230–262.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapkanov, Bozhidar. 2022. “Harmony and Tonality in the Late Piano Music of Franz Liszt: Functional and Transformational Analytical Perspectives.” PhD diss., City University of London.

Damschroder, David. 1981. “The Structural Foundations of ‘The Music of the Future’: A Schenkerian Study of Liszt’s Weimar Repertoire.” PhD diss., Yale University.

Ewell, Philip A. 2005. “Skryabin’s Dominant: The Evolution of a Harmonic Style.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 1: 118–148.

Forte, Allen. 1987. “Liszt’s Experimental Idiom and Music of the Early Twentieth Century.” 19th-Century Music 10/3: 209–228.

Garcia, Federico. 2006. “Liszt’s ‘Bagatelle Without Tonality’: Analytical Perspectives.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

Guenther, Roy J. 1983. “Varvara Dernova’s System of Analysis of the Music of Skryabin.” In Russian Theoretical Thought in Music, edited by Gordon D. McQuere, 165–216. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Kholopov, Yuriy. 1974. Ocherki sovremennoy garmonii. Moscow: Muzïka.

Kholopov, Yuriy. 1983. “Kto izobryol 12-tonovuyu tekhniku?” In Problemï istorii avstro-nemetskoy muzïki: Pervaya tret’ XX veka, 34–58. Moscow: Gosudarstvennïy muzïkal’no-pedagogicheskiy institut imeni Gnesinïkh.

Kholopov, Yuriy. 2003. Garmoniya: Prakticheskiy kurs, 2nd ed. Saint Petersburg: Lan’.

Lemoine, Bernard C. 1981. “Tonal Organization in Selected Late Piano Works of Franz Liszt.” In Referate des 2. Europäischen Liszt-Symposions: Eisenstadt 1978, edited by Serge Gut, 123–131. Munich: Musikverlag Emil Katzbichler.

Loya, Shay. 2011. Liszt’s Transcultural Modernism and the Hungarian-Gypsy Tradition. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Loya, Shay. 2022. “Liszt’s ‘Keyless’ Jest and the Historical Imagination.” Presented at the Newcastle Music Analysis Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, 11–13 July.

Lym, Sang-Hee. 1999. “Aspects of Compositional Technique in the Late Original Solo Piano Pieces by Franz Liszt.” DMA diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Morgan, Robert P. 1976. “Dissonant Prolongation: Theoretical and Compositional Precedents.” Journal of Music Theory 20/1 (1976): 49–91.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1990. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer.

Rothstein, William. 2009. “Riding the Storm Clouds: Tempo, Rhythm, and Meter in Beethoven’s Tempest Sonata.” In Beethoven’s “Tempest” Sonata: Perspectives of Analysis and Performance, edited by Pieter Bergé, 235–271. Leuven: Peeters.

Saslaw, Janna. 1990–91. “Gottfried Weber and Multiple Meaning.” Theoria 5: 74–103.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, Harold Adams. 1974. “The Evolution of Whole-Tone Sound in Liszt’s Original Piano Works.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2017. The Romantic Overture and Musical Form from Rossini to Wagner. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Notes

- I extend my sincere gratitude to Ellen Bakulina, David Carson Berry, and Shay Loya for their feedback on drafts of the manuscript.

On Liszt’s engagement with Zukunftsmusik, the “music of the future,” see Damschroder (1981), Forte (1987), and Berry (2004, 248–259). - Bozhidor Chapkanov (2022, 243–257) argues that the work’s surface effects are more important than the question of large-scale tonality, and he employs neo-Riemannian voice-leading transformations to model them.

- Evidently Kholopov changed his perspective on the work, as in an earlier book he wrote that the title of the Bagatelle ohne Tonart is self-explanatory (1974, 21).

- Shay Loya (2011, 243) also remarks on the importance of B minor in the Bagatelle. Loya (2022) further explores tonal hearings of the piece in ways compatible with the present analysis.

- The Russian term is prervannïy kadans, literally “interrupted cadence,” and although it corresponds to the English-language deceptive cadence (e.g., V–VI), the idea of the cadential progression being “interrupted” is evocative here.

- This corresponds closely to Berry’s (2004, 234) division of the work, except that Berry refers to my section C as a coda.

- As my argument is not primarily formal, my analysis does not engage with the real-time retrospective reinterpretation that is integral to the Romantic listening experience (Schmalfeldt 2011, Vande Moortele 2017), and which could be brought to bear on the Bagatelle.

- William Rothstein (1989, 184) memorably refers to the ubiquity of such hypermetrical regularity as the “Great Nineteenth-Century Rhythm Problem.”

- Throughout my discussion, “measure” refers to the notated measure in the original score, and “hypermeasure” to the larger metrical units diagrammed below in Example 1.

- My wording intentionally recalls that of William Rothstein (2009, 263), who further writes (of his own reduction): “To facilitate performance, I have occasionally altered the registers of notes.… I have, of course, omitted many notes, mostly through a process of dis-embellishment and textural simplification.… The point is that the reduction should sound. It is meaningless until it is played and heard, or heard accurately in the reader’s imagination.”

- My B-minor hearing reads the G–B–D–F “chord” in m. 13 as apparent only, with the F as a non-chord tone. Alternatively, several others have interpreted it as a functional dominant seventh with a root of G; Berry (2004), Lym (1999), and Garcia (2006) hear a tonicization of C major on this basis. Morgan (1976) initiates his G$$\sharp$$–B–D–F prolongation here, with G$$\natural$$ inflecting to G$$\sharp$$ over the course of the piece.

- Berry (2004) hears the augmented triad as an altered D-major local tonic that resolves the altered A7 dominant of m. 37. This perspective is well supported by Liszt’s engagement with Carl Friedrich Weitzmann’s treatise on the augmented triad, as Berry documents.

- Ellen Bakulina (2015a, 94; 2015b) was the first to present Kholopov’s “states of tonality” to an English-language audience. Bakulina 2015b furthermore provided a translation of relevant passages from Kholopov 2003.

- To invoke the terminology that Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990) borrows from semiology, Kholopov views the states of tonality as poietic phenomena based on compositional processes, whereas I adopt them as esthesic phenomena based on listening processes.

- Berry (2004, 259–261) discusses two of Schoenberg’s categories that resemble certain of Kholopov’s states of tonality: schwebende Tonalität (fluctuating tonality) and aufgehobene Tonalität (roving tonality). Schoenberg’s fluctuating tonality involves an ambiguous tonal center, whereas Kholopov’s floating tonality involves a determinate tonal center but absent tonic. Schoenberg furnished his song “Lockung,” op. 6, no. 7, as an exemplar. Intriguingly, Kholopov categorizes the same “Lockung” under floating tonality. Roving tonality involves constant changes of key, as in the development section of a sonata-form movement, in which each passed-through key area may or may not present its tonic chord.

- Although Morgan (1976, 79–86) interprets the final A$$\flat$$ altered dominant seventh of “Enigma” as the work’s “tonic” sonority, Roy Guenther (1983, 179) and James Baker (1983, 178) hear it with dominant function and understand the final tonic to be withheld. My B-minor reading of Liszt’s Bagatelle recalls Baker’s assessment of the end of “Enigma”: “The ultimate cadence to D$$\flat$$ must be assumed to take place, if at all, after the piece has ended” (ibid.). Philip Ewell (2005, 139–144) interprets another representative late Scriabin work, “Mask,” op. 63, no. 1 (1911), as prolonging a dominant ninth that never resolves to tonic.