Liam Hynes-Tawa

View PDFSuggested Citation

Return to Volume 34

We all know the story. Claudio Monteverdi is so modern and rebellious that he dares to write an unprepared ninth and seventh into the setting of Cruda Amarilli that opens his fifth book of madrigals, and a stodgy fellow named Giovanni Maria Artusi grumbles about it loudly enough that tonality begins. If we know the slightly more nuanced version of the story, we might also know that Artusi’s angry reproduction of the dissonant passage left out its text (Ahi, lasso!), and that the Monteverdi brothers explained in their reply that the text was of utmost importance to Claudio’s decision to publish such flagrantly non-traditional dissonance treatment. And thus we all learn some version of the story that common-practice tonality, and its all-important dominant seventh chord, arose out of a felt need to express text more expressively, and that eventually these text-setting licenses became so popular that they spread to instrumental music as well, and suddenly there we are in the High Baroque, putting Roman numerals under Bach chorales.

Megan Kaes Long’s Hearing Homophony: Tonal Expectation at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century not only argues against this story, but also turns it exactly on its head. What if, Long asks us, tonality arose not because composers wanted to set text expressively, but rather because they wanted to set it inexpressively? Susan McClary is already on record writing that despite the mythology surrounding them, Monteverdi’s madrigals are not particularly tonal, and if anything point away from the incipient tonality already audible in the frottola (8).1 What Long’s book does is to propose a radically different account of the forces that gave rise to those characteristics that we now habitually identify as tonal.

If I had to choose, “tonal” might claim second prize in the category “music terminology that makes me wary.” First prize would go to “modal,” which Long handily does away with in her very first chapter. But my close second, “tonal,” is right there in the title, and so it is clear from the start that Long will be spending a great deal of time with it over the course of the book.

Long assures the skeptical reader early on that she is being intentional and precise with her use of the term “tonal”; as she puts it, “I believe we should narrow our focus to consider single panels in the tapestry of tonality and tug on the particular threads that combine to form one compelling figure. We won’t understand tonality fully if we only gaze on the tapestry from a distance” (3). For her in this book, discussions of tonality always tie in with “expectation,” the next word in the title. By contrast, her first chapter makes sure to distance her project from a related phrase, “harmonic tonality,” whose purview is too large and ungainly to serve well in Long’s study, which needs the sharp focus that she brings it. By bracketing “harmonic tonality” and mode off to the side, she clears the oft-murky ground around the concept of tonality to make room for the more focused question of how pitch material can be used to create expectation for other pitches further down the line; and, as happens with the best of such studies, her focus on a particular question and an even more particular repertory ends up having meaningful implications that readers can easily transfer to the tonal or questionably-tonal repertories of their choice.

Most of Long’s study is centered around the balletto, a light genre that is not often given attention either in the performance world or in the grand narrative of music history that we all imbibe during our courses of study. But Long explains her reason for focusing on it early on, and sticks to it: “they strategically deployed dominant harmonies at regular periodicities and in combination with poetic, phrase structural, and formal cues, thereby creating expectation for tonic harmonies” (3). The genre’s simple homophonic texture forced composers to center their energies on parameters other than those that tended to hold sway in more complexly polyphonic genres, generating tonal expectation in a way that was new at the time, but has remained with us ever since.

As Kyle Adams notes on one of the book’s dustjacket blurbs, the parameters that these balletto composers had to foreground were precisely those that are so often excluded from discussions of tonality: rhythm, texture, and text-setting, to which I might also add meter on many hierarchized levels. As Long notes in her last chapter, which takes brief looks at a few other homophonic genres (the frottola, musique mesurée, and the Lutheran chorale), homophony tends to arise when making the text more easily understood is an important concern. But the balletto, with supplemental studies of the companion canzonetta genre along the way, provides Long with a particularly fruitful corpus because it is so predictable: as the pieces go on, one’s attention is drawn more and more to the long-range relationships established by the hypermetrically-regular placement of cadences on the same few scale degrees. This regularity—not only within individual songs but across the corpora at hand—trains listeners to hear a V in m. 8 forecasting a I in m. 16, no matter what the intervening chords may be.

This may be one of the most important points to highlight about Long’s book, which can often feel like an implicitly learned lesson even though Long does state it explicitly a few times: that “tonal expectation is a feature of large-scale harmonic frameworks rather than surface-level chord syntax” (18). This view runs counter to Edward Lowinsky’s idea of the cadence as the “cradle of tonality” (1961, 4), which suggests that the expanding sixth-to-octave cadence, as long as the semitone rose rather than fell, was so conducive to V-I harmonization that the habit ossified and eventually propagated outward, such that this basic cadential harmonization eventually governed more and more of the music on larger and larger levels. Long challenges this trajectory by suggesting instead that local chord-to-chord syntax followed the long-range positioning of multiple cadences throughout the form, with the latter being the crucial factor after which the more local progressions could be filled in as a comparatively inconsequential aftereffect. This contention naturally brings up the question of whether one can actually hear the long-range tonal architectures for which Classical and Romantic multi-movement behemoths are famous, but the advantage of the balletto is that it is so short and repetitive that one has no choice but to hear these tonal relationships—as Long puts it, it lies “at the intersection of phrase structure and form” (166). The implication seems to be that the type of tonal expectation engendered in the balletto here entered the realm of possible techniques, even if it would take about another century for it to take over as the central one.

One great advantage to Long’s focusing so closely on one genre made up of such short pieces (or two genres, if one counts the canzonetta as separate) is that it allows her to present to us a sizable corpus of pieces that the reader becomes familiar with just by reading the book. The pieces are short and simple enough that anyone with a decent education in sight-singing can get a feel for them just by humming along to the clearly-printed and generously-annotated two-staff transcriptions with which Long has kindly filled the book. There is even a companion website that gives one the opportunity to do so in the virtual company of a lovely chorus (which includes the author herself!), sometimes with lute accompaniment.2 Singing through these songs together with them—which I found myself doing more for amusement than to intentionally study the genre—helps reveal to the reader aspects of this music that no prose writer, no matter how lucid, could elucidate, but which do have to do with the senses of mid-to-long-range expectation that is the centerpiece of Long’s account. Especially because she stresses that this was music made for the singers rather than for a non-participatory audience, this facilitation of participation on the reader’s part is not simply a nice bonus, but rather a crucial part of understanding her argument.

Despite the inclusion of such audio and notational resources, however, Long still does her very best to help the reader of her prose to understand the experience that this music creates for the singer and/or listener. Long’s skill and experience as a singer allow her to speak from the point of view of the oft-neglected alto, giving readers a valuable view into the inner reaches of these pieces’ textures—which, again, is especially crucial for a repertory like this in which the primary audience was always the singers themselves.

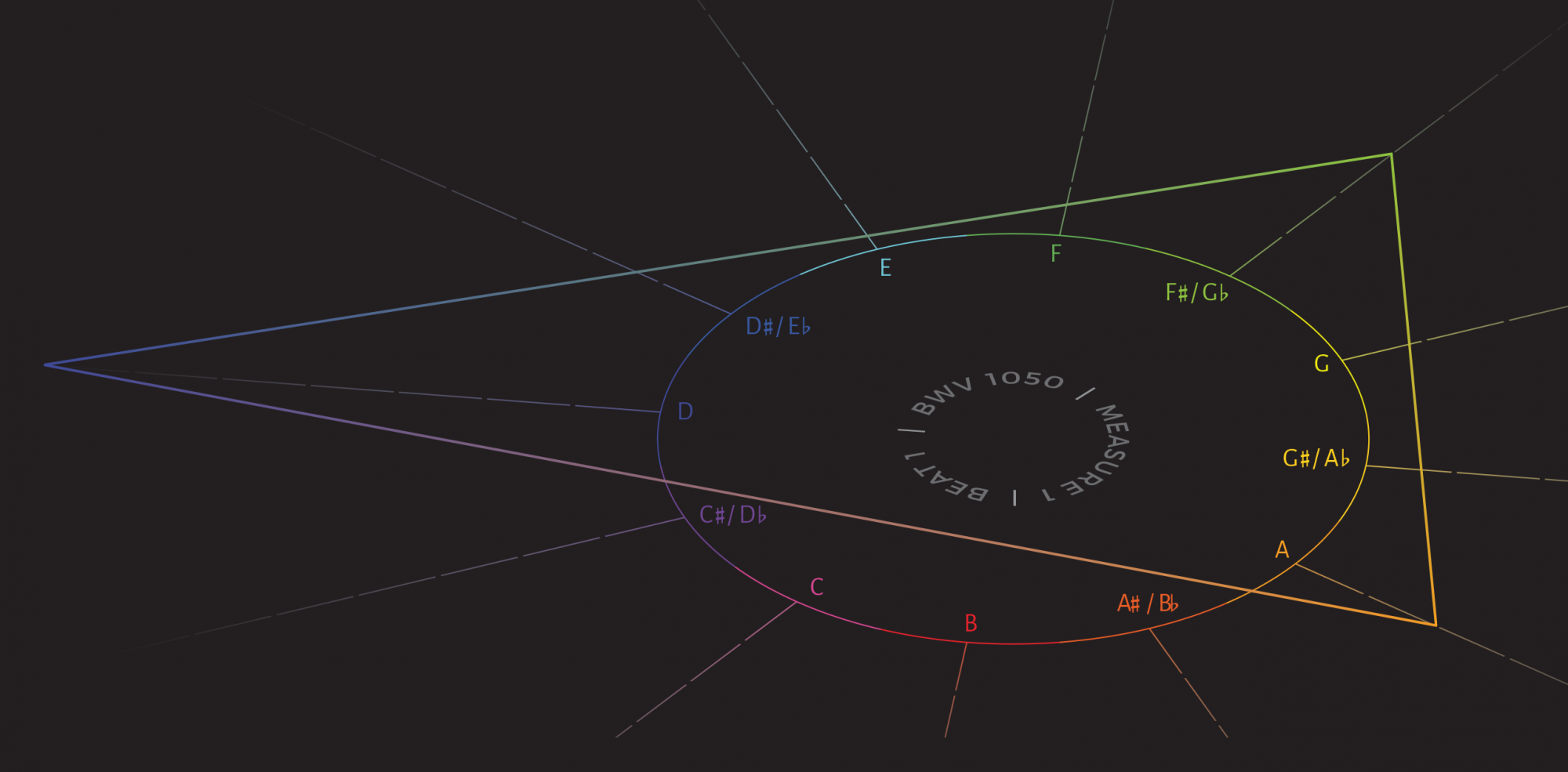

Furthermore, extended analogies to the painting of miniatures and to city cartography govern the fifth and sixth chapters respectively, and the latter case is especially extensive, with Long comparing the project of mapping out a city from a bird’s-eye perspective to that of comprehending the full tonal form of a piece of music all at once, from an out-of-time perspective. The analogy recurs regularly and ties the whole chapter together, giving readers a way to visualize the process occurring in their brains as their relationship with a piece grows towards the synoptic level, which happens at a uniquely quick rate in the balletto. Long presents the analogy with the caveat that she does not mean to suggest that the coexistence of the cartographical and musical practices she describes in the same time and place are meant as a statement about different arts in the same cultural sphere influencing each other, but it is hard not to draw the conclusion that there might be some link, based on a culture newly interested in mapping out the known world and, at least in England, reaching towards building its empire (175). An article that came to mind for me when reading this passage was Christopher Field’s “Jenkins and the Cosmography of Harmony” (1996) on the concept of circumnavigation: he suggests that an interest in exploring the totality of the globe in the seventeenth century is indeed reflected in “circumnavigational” pieces of this era, in which a complete chromatic circle of fifths is at some point achieved, inevitably with at least one enharmonic respelling en route. It probably would have taken Long too far afield from her main purpose to prove or more explicitly argue for a cultural link between cartography and tonality in this way, and perhaps she was concerned about not letting it spin too far out of control. In any case, even though she intentionally stops short of pursuing this perhaps tangential link, she does open us up to think about it more, and lays the ground for the tonal side of a potential future study along these lines.

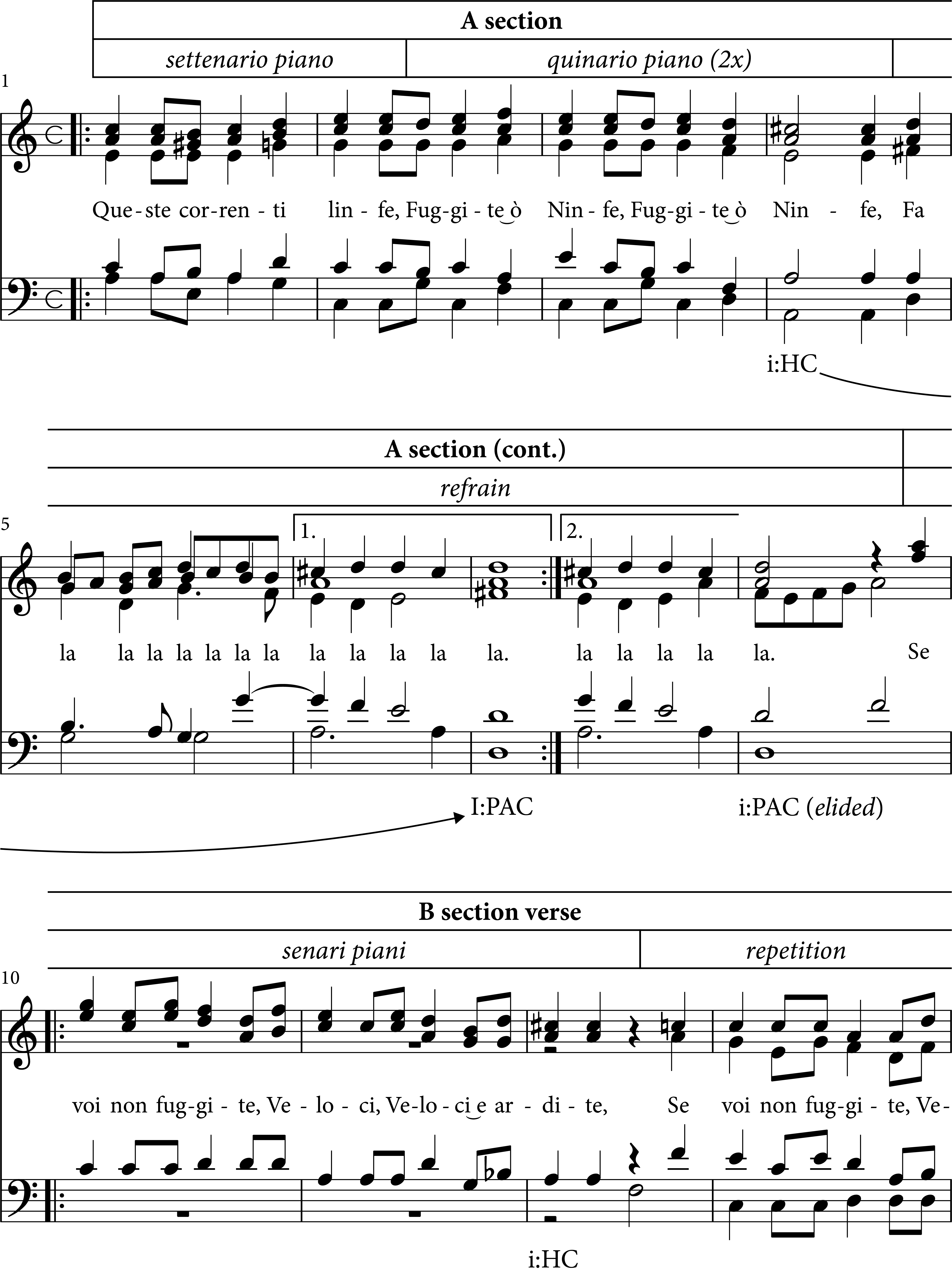

Another question that arose for me, this one in the more granular sphere of tabulating pitch-related events to draw up a tonal map of a piece, is whether cadences really are the only and best “landmarks” that one can place on one’s tonal map when listening to a piece from this period and figuring out how it creates its sense of tonal expectation. Long reproduces Gastoldi’s Caccia d’Amore as her Example 6.5 (included here as Example 1), commenting enlighteningly on how the “bonus refrain” in its second section may seem to violate the balletto’s formal norms, but in fact only clarifies the sense of harmony and form reinforcing each other and creating a strong sense of tonal expectation (186). Her analysis of this balletto’s second section, and its effects, is unimpeachable. But I did stumble a bit when reading her account of its first section, which she calls “normative” (187). This is absolutely true as far as its cadential layout goes, which is after all what Long is tracking. In featuring a half cadence on A followed by an authentic cadence on the tonic D, followed by a repeat of that section with its two cadences, there would seem to be hardly any better candidate for an open-and-shut expression of D minor.

And yet when I listen to this balletto—or, even more, when I sing it—that is not quite the impression I am left with. After all, the first three of the section’s seven measures do not give us any hint that D is important at all. It begins on an A minor chord, oscillates back and forth with E major, and then proceeds to sit on C major for nearly two whole bars. Before m. 4’s A major chord, these first three measures would seem to be establishing tonal expectation for A minor, not D minor, and I must admit that I still hear the authentic cadence on D that arrives in m. 7 as a IV:PAC, not a I:PAC. None of this is to say that Long’s analysis is “wrong”—rather, it is to say that there are limits to cadence-based analysis, and that the mere act of sitting on a sonority, even without a cadence, may be enough to influence tonal expectation. Cadences have long been a natural feature to focus on in analyzing pre-Corelli music, because they are satisfyingly observable and nameable, and have clear effects on our hearing. But the material that exists in the spaces before and between cadences is, I would argue, just as effective, and Long’s emphasis on meter as such a crucial element of tonal perception may be just the avenue we need to figure out how these non-cadential areas affect one’s sense of tonality as well.

Another advantage of focusing so closely on the balletto is that Long is able to give us detailed and vivid portraits of how the genre’s style differed in the three countries in which it became popular. Far from a mere curiosity in the story of partsong fashion alone, Long elucidates at length how each national flavor of the genre represents a different strategy for imparting a sense of tonal expectation to a light homophonic genre like this. The English style’s strategy most resembles that of common-practice tonality: its tendency (especially Thomas Morley’s tendency, it seems) to place cadences on V such that a later cadence on I is set up to land in a predictable place is stronger than in Italian models, which rely more on tonic by assertion than by polarity (150–151). German composers, on the other hand, especially Hassler, are shown to rely a great deal on block transposition, which allows the transposition itself to take on some of the expectation-related work that, in English music, is accomplished more fully by the V-to-I polarity (124–128, 162). These characteristics of national taste are shown most clearly in songs like L’innamorato in which both English and German composers made their own versions of an Italian original (as Sing we and chant it and Tantzen und springen, respectively). Far from being mere translations of the text that keep the music as similar as possible, these are true localizations in which the musical content is adjusted to fit the tastes of the expected customers, and Long’s treatment of them all in close quarters helps to bring these differences in national taste to the reader’s attention in ways that likely they never have been before, at least as far as this genre is concerned.

But once again, these differences in taste tell us much more about tonality than merely what these localized habits were, because they reveal different strategies towards achieving the same goal. That goal was a homophonic style in which the words were intelligible but energy was still retained, by some means other than by the contrapuntal webs or vivid text-painting that characterized the weightier genres. All of the balletto strategies that Long outlines work towards creating tonal expectation, perhaps because the English and German composers observed (consciously or not) that Gastoldi had created such a sense, and then modified the details of their technique while still aiming for the same goal.

Another area in which Long’s book breaks with norms of analyzing texted music is the depth with which she addresses poetic meter. Perhaps because the florid style of the more exalted madrigal makes it possible to set almost any poetic line in a great variety of metric and rhythmic ways, most of which relate little to the type of poetic line in question, learning the vocabulary and taxonomy of Italian poesy is not typically part of the music theorist’s training. Long’s argument, however, is that the conditions that made poetic meter so salient in the balletto were precisely the same as those that made it such a ripe genre for engendering tonal expectation. Borrowing a term from Ruth DeFord (1985), Long distinguishes between dramatic text-setting (as we might find in a madrigal) from schematic (as we would find in a balletto), the latter of which sacrifices the richness of madrigalian text-painting but “has the benefit of encouraging musical rather than textual organization” (63). Its musical organization manifests in both meter and pitch, but its metric organization is, for the most part, simply inherited from the text itself, leaving pitch the primary domain in which these composers could experiment. The conclusion is therefore essentially that a focus on poetic meter gives rise to tonal expectation—or, even more succinctly, that tonality comes from meter (compare Prince and Schmuckler 2014). While this conclusion is not without precedent, Long’s book is among the first, if not the very first, to situate this connection so clearly in a particular historical and cultural phenomenon that motivated such a new way of approaching pitch organization in European music (4–5).

Following upon this useful distinction between dramatic and schematic text-setting, Long engages another dichotomy, this one inherited from Dahlhaus, between paratactic and hypotactic phrase structures (107). The difference between them—that paratactic phrases simply follow each other while hypotactic phrases are consequences of each other—snaps into clearer focus than ever before within Long’s poetic frame. The question of whether one musical gesture is a logical consequence—or even an inevitable one!—of what came before has long been a vexed and discomforting one, and it often all too easily slides into overtones of an Austro-German-supremacist flavor, largely due to the way that Beethoven and his imitators prioritized constructing phrases that sounded inevitable, and the mythology that built up around them afterwards for largely non-musical reasons. Long is able to avoid making any such specious claims about inevitability by placing her discussion of hypotaxis immediately after her discussion of poetic meter, of which one might almost say it feels like an inevitable consequence. The balletto’s faithful reproduction of poetic meters in and as musical meters means that without some new form of pitch-related logic, there would seem to be little meaning in setting these texts to music at all—it would approach unpitched recitation. Hypotaxis thus emerges as a byproduct of schematic text-setting, reinforcing the always-healthy reminder that no sixteenth- or seventeenth-century composer was trying (and therefore failing) to write common-practice tonal music, but rather that the myriad purposes to which they put music demanded different things of them—and in this case, the solution ended up looking quite similar to a future type of tonality, for reasons that had little to do with pitch or harmony at their roots.

A question that remains for me after reading this beautiful account of the balletto is what happened to its unique brand of tonality after its star faded, and to what extent it may be genealogically linked up to the tonality of Corelli and Vivaldi that more obviously inaugurated the tonal common practice that still governs how we learn about pitch organization. Were Gastoldi’s tunes such earworms that some memory of their effects persisted in the minds of future generations, such that they reached for similar techniques when they had need of those effects again? Or was the balletto’s high level of tonal expectation essentially a fluke, a unique solution to a particular set of circumstances that had to be more or less entirely rediscovered again later on in the century? Perhaps it doesn’t matter too much for Long’s project, which is concerned more with what factors can give rise to tonal expectation whenever it occurs than with the question of whether Gastoldi fits on the tonal family tree of Mozart and Beethoven. But Long’s study is also admirably historically aware and responsible, locating the origins of the balletto’s form of tonality in its particular cultural environments in which particular types of poetry were popular, and so it is natural to wonder how the balletto fad affected the structuring of pitch materials in other repertories that followed not too long afterward.

Her final chapter does go some way towards hinting at answers to this question, demonstrating how three other homophonic genres from a similar time period seem to have arisen in response to the same larger cultural trends—most broadly, humanism—that helped give rise to the balletto. Long’s argument is essentially that this humanistic spirit caused new importance to be placed on textual intelligibility in a variety of contexts, each of which independently gave rise to its own type of homophony; and that homophony is especially conducive to the development of musical styles that generate tonal expectation, causing some amount of tonal expectation to emerge multiple times in multiple contexts. Considering the amount of cultural exchange and cross-pollination going on in Europe at the time (as demonstrated by Long’s account of the balletto’s peregrinations), it is only to be expected that many independently arising tonal styles in such close quarters would soon enough meld into something approaching an international common practice. The reason questions remain, at least for me, is because Long is so convincing in arguing for the balletto’s uniquely transparent sense of tonality that lies, once again, “at the intersection of phrase structure and form” (166). Her portrait of the genre really makes it feel like something special, at the very least in hindsight, and not simply one out of however many other homophonic genres could equally well have played the starring role in her study.

Be that question as it may, the very fact of its existence points only to the strength of the picture Long has painted of the balletto. A genre that our Romantic lenses make us likely to ignore on account of its lightness turns out to be full of clues and questions that can point us any which way: towards understanding the history of Western tonality specifically, towards understanding some hidden fundamental relationship between pitch and meter, and perhaps even towards unlearning the bias we have inherited in favor of Art that comes in large, self-important packages. Long’s book helps us along the road to all three, and should not be expected to answer every one of the manifold questions that her study has raised—that can be the job of us who respond to it. And, to paraphrase Morley, “I hope before such time as we [have] sufficientlie ruminated & digested those precepts which she hath [given] us, that we shal heare from her in a new kind of matter” (1597, 182).

Liam Hynes-Tawa

Yale University

469 College Street

New Haven, CT 06511

liam.hynes@yale.edu

References

DeFord, Ruth I. 1985. “Musical Relationships between the Italian Madrigal and Light Genres in the Sixteenth Century.” Musica Disciplina 39: 107–168.

Field, Christopher. 1996. “Jenkins and the Cosmography of Harmony.” In John Jenkins and His Time: Studies in English Consort Music, edited by Ashbee and Holman, 1–74. New York: Oxford University Press.

Long, Megan Kaes. 2020. Hearing Homophony: Tonal Expectation at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lowinsky, Edward. 1961. Tonality and Atonality in Sixteenth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

McClary, Susan. 2004. Modal Subjectivities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Morley, Thomas. 1597. A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke. London: Peter Short. Facsimile accessible via IMSLP.

Prince, Jon and Mark Schmuckler. 2014. “The Tonal-Metric Hierarchy: A Corpus Analysis.” Music Perception 31 (3): 254–270.

Notes

- See McClary 2004, 6.

- www.oup.com/us/hearinghomophony