Saxophonist Charles Pillow performing at the 2017 Xerox Rochester International Jazz Festival

By Dan Gross

Charles Pillow, Eastman Assistant Professor of Jazz Saxophone, comes from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. After graduating from Loyola University, he pursued his Master’s Degree in Jazz Studies at the Eastman School of Music, where he is now an Assistant Professor of Jazz Saxophone . Since moving to New York City in 1987, he has appeared on over 100 recordings of jazz and pop luminaries such as Frank Sinatra, Mariah Carey, Jay Z, Luther Vandross, Paul Simon, Michael Brecker, Bruce Springsteen, John Scofield, Tom Harrell, Dave Liebman, David Sanborn, and so on. He has five solo recordings available: Currents, In this World, Pictures at an Exhibition, The Planets, and Van Gogh Letters. Known as a saxophonist, flutist, clarinetist, and oboist, his recordings showcase those instruments.

Charles is playing this year’s Xerox Rochester International Jazz Festival (XRIJF) with his trio, TRIOCITY, with Eastman professors Jeff Campbell on bass and Rich Thompson on drums.

When did you start playing music, and who were some of your early influences?

Like most kids do, I started in fourth or fifth grade. First I was on the drums, and I switched to saxophone in the sixth or seventh grade. I was fortunate enough to have a junior high school band director who was a saxophone player, and he turned me on to a Paul Desmond record.

When I went to the high school, we had a very well-known educator in Louisiana who been on the road with Woody Herman’s band. He ran a great program, and we would go down to New Orleans and play concerts and festivals. We competed against the Marsalis brothers when they were first coming up. It was a very healthy situation.

What first drew to you to playing jazz?

I would say hearing Paul Desmond and Dave Brubeck. It just seemed like the thing to do in the environment I was in, with the educators I had. Then I heard Charlie Parker and John Coltrane, and that cemented it right there.

What drew you to Eastman as a student?

The two or three saxophone teachers I had at Loyola University had just finished their Master’s degrees at Eastman. It just made sense to try to go to Eastman; I didn’t care what the weather was, I just knew I had to be there. It was another lucky thing … I got to study with Ray Wright, Ray Ricker, and Bill Dobbins.

Forget rock and roll, that’s a power trio right there. Do you have one story from those guys you’d like to share?

Ray Wright was a brilliant guy – in many ways – and he had a great sense of humor. He had us write a big band chart for his Jazz Arranging class, so I wrote a chart on “Dolphin Dance” by Herbie Hancock. In the intro, I had these big suspended chords that the brass would play. He had me stand in front of the band, I counted the tune off, and they would play the intro.

He stopped the band and looked at me, and he said: “What do you think?” I’m grinning ear to ear, because I think it sounds fantastic! We do it again, and he asked me the same thing! To this day, I still don’t know what was wrong! I talked to arrangers since then, and they think it may have been some parallel fifths or something.

He was one of those guys who would let you try and figure it out. I did not figure it out, but I’m still thinking about it.

What’s it like for you going from being a student at Eastman to a professor at Eastman?

It was very enjoyable, and it still is. It’s an honor to be here. Eastman has such a great history, and is known all over the world. The students are very serious, and I take the job very seriously. I try – as well as I can – to listen to what the students want, and try to decipher their fears, and hopes.

Everyone learns differently, and you want to be supportive, but hard enough on them so they get the most out of it. I think what I want to show them is not what there is to learn, but show them how they need to learn it.

You’re playing this year’s XRIJF on Sunday, the 24th, with TRIOCITY in the Wilder Room. Can you tell us about that show?

We released a record last summer about this time, and we mainly play standards. Most of the records I’ve done have been original material. So we wanted to dedicate this band to playing the Great American Songbook. It’s a chordless style, without a piano or guitar. It’s always fun to play with those guys [Jeff Campbell and Rich Thompson], and we teach together!

What does it mean for you to play the XRIJF?

It’s a great thing for the city, it’s an honor to be there, there are so many great names and performances from students to professionals. It’s especially good for Eastman students. They get to play at these venues, and it’s very exciting.

I also really like the way they organize it; people can go and hear half a set, and then leave, and walk just a couple of minutes to the next one! The staggered start times help with that too. It’s a healthy way for an area downtown to be immersed in music and have a great hang. This is the fourth time I’ve played in the eight years I’ve been teaching. It’s been an honor.

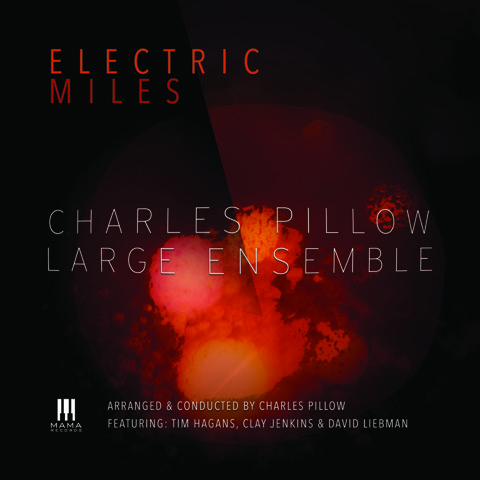

Charles also released an album on June 22nd: Electric Miles, on the Summit/MaMa label. Electric Miles is a large ensemble arrangement and adaptation of Miles Davis’ seminal recording from 1969, Bitches Brew. This music ushered in the “fusion” era and featured such up and coming artists as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, and others.

Featured soloists on Electric Miles are Tim Hagans on trumpet, NEA Jazz Master Dave Liebman on saxophone, Clay Jenkins on trumpet, and Charles on alto sax and alto flute. Some well-known Eastman alumni are also featured: Michael Davis’82E on trombone, and Jared Schonig’05E on drums. Rounding out the band are recent Eastman alumni: Luke Norris ’17E, tenor sax; CJ Ziarniak ’17E, tenor sax; Karl Stabnau ’11E, bass clarinet; Charlie Carr ’17E (DMA), trumpet; and Julian Garvue ’17E, electric piano, along with current students: Colin Gordon DMA, Abe Nouri ’18E, Jack Courtright ’18E, Gabe Ramos BM.

Tell us about Electric Miles!

A number of the tunes come from Bitches Brew, but some tunes are from [other Miles Davis albums] In a Silent Way, Jack Johnson, and one or two others. Bitches Brew has so much mystique wrapped around it. I feel like that music is underappreciated still, even though it’s one of Miles’s best-selling records, along with Kind of Blue.

I think it not only had a mystique, but my generation that grew up with that record, admired what was happening. If you look at who was on that record, it was the guys who started the whole fusion movement: Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland.

The other thing I think is underappreciated about the album is that [album producer] Teo Macero – who put the whole thing together – was a composer himself. He knew classical composition techniques. Teo was like George Martin of The Beatles. He was the brains behind Miles, but there’s more thematic material than you think on those records, once you start to listen to them. Apparently, Bitches Brew was supposed to be a five-movement suite, but it was condensed to what it is now.

It was Miles’ policy in the studio to keep the tape running, which was very expensive in those days. They recorded everything. This took the whole editing process to another level.

I just wanted to put that music into a large ensemble format. Doing it I learned so much. I wanted the excitement of a large ensemble, and basically made a vehicle for trumpet soloists, namely Tim Hagans and Clay Jenkins. They did such a fantastic job evoking the spirit of Miles.

Tell us about your arranging process.

I was trying to figure out what was important thematically. A couple of the tunes are simpler. “Pharaoh’s Dance” was one that has more thematic material … and even there Miles doesn’t play the melody until the very end, and I don’t know if that was done on purpose or not, but the way he skirts around the melody, you almost have to listen to it twenty times to figure out that’s a melody. You had to dig into that. It was really figuring out what was important, and what I should highlight to allow room for the soloists.

You put this record together in opposite order of most bands; you recorded the album and then the day after, you played it at last year’s XRIJF! Did you think it would be more fun?

I have no idea why I did that! It just worked out with the schedule. I want to thank John Nugent for having us, and it was a lucky circumstance that it all shook out. I had already planned tentatively on recording it in Rochester the day before, and John gave me the day after. Which isn’t a bad way to do it, now that I think about it. Sometimes, recording music you haven’t fully rehearsed can actually be a really good situation; it catches everyone in their most emotionally and intellectually alive state. You’re a little afraid, but good music comes out of that.