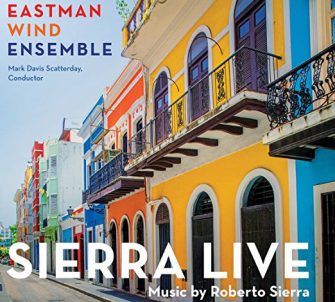

The Eastman School of Music’s Eastman Wind Ensemble has released a new CD that features works by Puerto Rico’s best-known composer, five-time Grammy nominee Roberto Sierra.

The Eastman School of Music’s Eastman Wind Ensemble has released a new CD that features works by Puerto Rico’s best-known composer, five-time Grammy nominee Roberto Sierra.

Titled Sierra Live: Music by Roberto Sierra, the recording has earned praise from Fanfare magazine for performance of the works “at the highest possible artistic level,” noting that the “skill with which these pieces are presented is all the more remarkable given that these are all live performances.”

The 12 tracks on the Summit Records label CD were recorded over a decade’s worth of Eastman Wind Ensemble concerts in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. Seeking to make the highest quality live recording, Conductor Mark Davis Scatterday rotated the selected repertoire over the years, selecting the best performances for the recording.

“Each one of the works was presented three times over that time period,” said Scatterday, who is Professor and Chair of Conducting and Ensembles. “Because each piece is performed by a different EWE, there are over 200 different Eastman musicians performing on the finished CD.”

Scatterday has known and worked with Sierra for 25 years, first meeting the composer as a faculty member at Cornell University. An active arranger of orchestral music for wind ensemble, Scatterday transcribed Sierra’s Symphony No. 3, “La Salsa,” whose four movements are included on the new CD.

Other works on Sierra Live are Fandangos, a festive and colorful version of a Spanish dance; Alegriá, whose title translates to “Joy;” Fanfarria, which was originally written for brass and percussion and was also transcribed for full wind ensemble by Scatterday; and Diferancias, which was commissioned by a consortium of university wind ensembles and premiered at Cornell in 1997.

Sierra was born in 1953 in Puerto Rico and studied composition both in Puerto Rico and Europe, where one of his teachers was György Ligeti. His works have been commissioned and performed by major American and European orchestras and ensembles, including the orchestras of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Houston, Minnesota, Dallas, Detroit, Madrid, Galicia, Castilla y León, and Barcelona, as well as the American Composers Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony Orchestra, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and the Tonhalle Orchestra of Zurich. In 2003, Sierra was awarded the Academy Award in Music by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and he was elected to the Academy in 2010.

Sierra Live is available on Summit Records, Amazon, iTunes, and Spotify.

The Eastman Wind Ensemble has been in the forefront of elevating the wind repertory through recordings since its founding by Frederick Fennell at the Eastman School of Music in 1952. The Ensemble has made more than 50 recordings on the Mercury, Sony, Warner Brothers, and Summit Records labels, and has premiered more than 150 new works. The Ensemble has done major tours of the United States, Japan, and the Far East, most recently a six-city, 12-day tour in Europe, and has been invited to perform at many festivals and music conferences.

# # #