This excerpt from the autobiography of the father of former Eastman School director Robert Freeman was published in Eastman Notes magazine this fall, shortly before Robert Freeman’s death on October 18, 2022, in Austin, Texas. We also offer the story on the Eastman website in tribute to Bob Freeman, who led Eastman from 1973 to 1996 … and also in tribute to his remarkable family, whose story is fully told in An American Dream, Realized.

You can read more about Robert Freeman’s life and work, and his achievements at Eastman, at this website.

Henry Schofield Freeman ‘30E (1909-1997) had a remarkable career as a double bassist, and a remarkable life in general. Unlike many of us, however, he wrote his down. About thirty years after its completion, his autobiography was finally published in 2020 by Henry’s sons Robert and James.

James Freeman is a professor emeritus of music at Swarthmore College; Robert Freeman, of course, was the director of the Eastman School of Music from 1972 to 1996. An American Dream, Realized was written from about 1982 to 1992, with a postscript added in 1994. Henry died in 1997, and James and Bob bring the family story up to date in a “Postlude.”

Because Henry’s father, a trumpeter who had played for John Philip Sousa, was the first professor of trumpet at Eastman, and because Henry was the first double bass student at Eastman (against his father’s wishes) and performed in the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in the 1920s, his autobiography also offers interesting glimpses of our school almost a century ago, and of a Rochester full of theaters, restaurants, hotels, and radio stations offering live music.

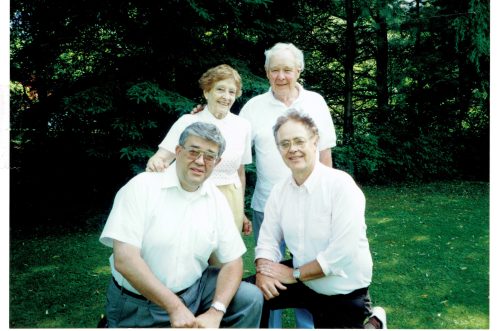

The Freeman family in 1944. Back: Florence and Henry; front, Bob and Jim.

“We think the memoir is so compelling a history of one man’s life that it deserves to be read by many people,” the Freeman brothers write in their preface. “It is a love story first of all, but it is also a story of an adventurous and often wild boyhood in the tenements of New York City in the 1910s and early ‘20s; of becoming a musician against all odds in Rochester, New York; of reaching the pinnacle of success for a bass player in 1945, a position in the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitsky, in which he eventually advanced to principal bass; and of his always passionate romance with his beloved wife, Florence, and their two sons.”

In one chapter, Henry described how he acquired his valuable Italian bass, which led to that position in the BSO, held until 1967 under three fabled music directors: Koussevitsky, Charles Munch, and Erich Leinsdorf.

The Italian Bass

…I must go back to the summer of 1932 and recount the story of how I became the proud and lucky owner of my Italian double bass (with the name “Pani Gian Carlo” inscribed by hand on a white label glued to the middle of the back). In the spring of that year, my teacher, Nelson Watson, announced that he would be going back to England, with his family, for a summer’s visit, and especially to see his brother, Victor, somewhat older, who had been principal bass of the London Symphony for years. It was then that, if he found a good bass at a reasonable price, I ventured the hope that he would bring it back and sell it to me. As it turned out, his brother sold or gave him this Italian bass to take back to the USA, ostensibly for his own use. After getting it home, trying it for a while, and finding it difficult to adjust to its softer qualities, as compared to his massively projecting Dodd, he finally turned it over to me to try, quoting an asking price of $250.

So, for the next month, I kept trying it out and, little by little, finding just how to get the maximum response from the instrument. Then, when Watson demanded, at last, a “Yes” or “No” answer, I knew I didn’t want to give up that bass, and that very night, with all the RPO basses lined up on the stage for a concert in two hours, I got there early, persuaded my friend Ben Connally (the stage manager) to turn on the stage lights while I tried playing the Italian and then Watson’s Dodd, while Connally went way out to the back of the theatre, underneath the mezzanine balcony, to listen. His judgement was unequivocal that the Italian bass carried louder and further! So that night I agreed to buy the bass and gave Watson a check, the next morning, for the $250.

Shortly, I took it over to Bert Goodwin, a natural and masterful luthier, and asked him to suggest improvements. He immediately said that a new and larger bass bar was needed, and I told him to go ahead. My recollection is that he had the top off the next morning, and that I was appalled by the lifelessness of that sturdy-looking instrument once the top was off! Then, while I looked on, he quickly and expertly sliced off the old bass bar with a chisel. And, in a couple of days, he had fashioned a new and much heavier bass bar and had glued it to the underside of the right side of the top. He also glued several rib cracks and filled in some thin spots in the back before gluing it back on to the ribs.

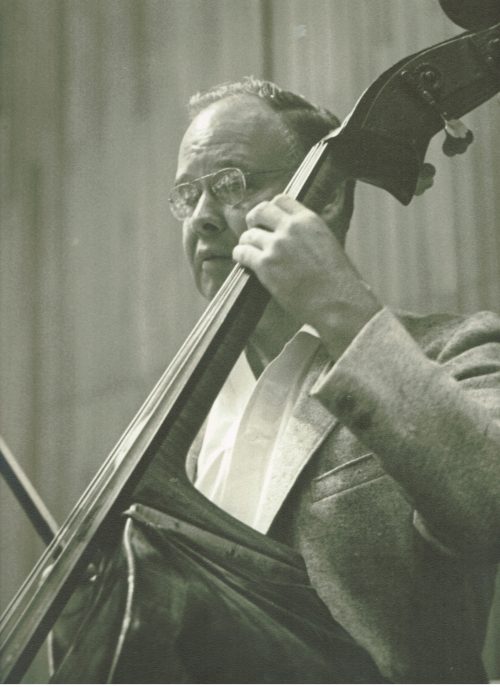

Henry Freeman in the Boston Symphony Orchestra with his prized Italian bass, early 1960s.

It was also determined at this time that the very old finely machined peg mechanism would have to go, since the gears were badly worn (through a couple of centuries of use) and would have to be replaced, which was a shame, since those machines, with the beautiful solid brass plates, would no longer fit the new peg holes, Sadly, the only machines available at that time were poor replacements and had been finished with a black lacquer, which I proceeded to scrape off, laboriously, with a pen knife!

Not too much later, a new higher bridge and the first set of steel strings in the East were added. The strings, a new innovation by the Black Diamond Company of New Brunswick, New Jersey, were made of spun aluminum on steel cores, and, while to me this was like night and day, they also tended to dirty your fingers because of the aluminum oxide that got deposited on your fingers as you played.

Also, in those very early days of metal strings, the strings, even with “bridge protectors,” tended to break at the bridge when fortissimo was played. This was expensive (as were the strings), but I contrived many times to let some string length out of the peg box and then tie the two broken ends together, with a square knot, just below the bridge!

At any rate, little by little I learned to play that bass and to get the maximum out of it. Because of its softer nature, I found that in order to project, especially in a tutti string section, and to be sure of my intonation, over the years I devised a fingering system that anchored in the main, reliable positions, and yet took advantage of the strength and oomph that lay in the higher positions of the lower strings. So it was, when I did get that chance of a lifetime to play for “Koussie,” I really opened his eyes and ears, what with the steel strings (and their power) – which I’m sure he had never seen or heard before – and the originality and conception of my technique.

That Italian bass – with its $250 price tag – was the vehicle that, at the end of a 45-minute audition, brought him to embrace me, with his arm around my shoulder, and say, “I must have you in mein Orchester. You are a fine, strong player!” When the Rochester authorities wouldn’t release me from my contract, he made a new opening for me in his fabulous bass section, two years later.

Watson, who played in front of me or beside me, would often turn around and mutter, “Anytime that you want your money back on that bass, let me know!” Then, in the meantime, when he died suddenly (at age 54), and I was just about to take up my new position in Boston, I outbid all the others and bought his famous Dodd bass for a thousand dollars cash, and his two fine bows for $100 each! Those were pretty good prices in 1945!

The Freeman family in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 1992.