Issue No. 9: October, 1999

Publisher’s Notes by Paul R. Judy

Announcements

Organizational Consultation and Research Programs

Leadership and Trust by Joe Goodell

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra by Erin V. Lehman

Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra: A Cooperative Institution by Paul R. Judy

Organizational Effectiveness: The Role of the Board of Directors by Paul R. Judy

Book Review: High Performance Nonprofit Organizations: Managing Upstream for Greater Impact by Roland Velliere

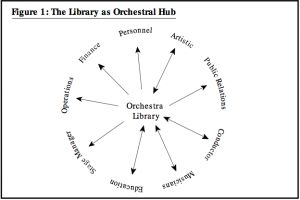

Behind the Scenes: A Roundtable by Stephen Belth

he Marketing Process by Stephen Belth

About the Cover… by Phillip Huscher

Publisher’s Notes

Students of symphony orchestra organizations continuously learn about the complexity of these organizational systems, a complexity that never ceases to amaze me. This issue’s content, as it came alive, nicely extends the path of discovery. As you read on, perhaps in quiet concentration, I hope you will join me in reflection and learning. Symphony organizations are, indeed, unique, and their sustenance and enhancement calls for special organizational awareness and study. For the many readers who are active participants in symphony organizations, we hope this issue will advance their knowledge and add to the momentum for improvement of these vital community institutions.

A few years ago, on my annual summer sojourn from Chicago to Nantucket, I stopped to visit Joe Goodell, a retired businessman who had recently been drafted to fill the position of executive director of the Buffalo Philharmonic. Since Joe had no symphony staff experience, many felt that under his leadership Buffalo’s prospects for remediating deep and long-standing organizational problems were very dim. During lunch, I came to a contrary prediction, and asked Joe to write about his symphony management experience at some future date. Joe has responded and, as you will soon learn, he minces no words. Participants in every role within a symphony organization will find his point of view to be sharp and thought provoking.

In the next two articles, the perspective shifts from that of an organizational participant to that of an organizational observer and reporter. We juxtapose case studies of two orchestral institutions, one German and one American, which are quite different in age, size, and reputation, but which have in common many organizational features and practices distinctly different from those employed in the traditional North American organizational form.

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra was founded as a cooperative orchestra in 1882, as a successor to a proprietary entity originated 14 years earlier. Erin Lehman, a long-time student of orchestral organizations, has summarized how the Berlin Philharmonic functions as a “self-governing” orchestra. As readers will learn, the basic authority for artistic decisions has long been vested in the orchestra and is exercised through elected representatives, as well as by the orchestra acting as a whole. Administrative and financial-support decisions involve intertwining orchestral leadership with a general administrator and staff, and a municipal government. As is the case for most of the world’s orchestral systems, the Berlin Philharmonic is having to adapt to environmental changes, but will address these challenges through decision-making processes which are quite different from those of almost all of its North American counterparts.

The Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra was founded as a cooperative orchestra, succeeding a traditionally organized New Orleans institution established in the mid-1930s which went out of business in 1991. Based on field interviews and institutional documents, we summarize how the Louisiana Philharmonic was founded, how it is organized, and how it makes artistic, operational, and financial decisions. In a striking contrast to the long-term, evolutionary development of the Berlin Philharmonic, the way in which the Louisiana Philharmonic generally is organized and functions was designed from scratch and in thorough detail just eight years ago, and, in good part, around a kitchen table. And further, the orchestra was created, with some subsequent adjustments, to fit within the American framework of a charitably supported, nonprofit corporation, with a large and active volunteer constituency. Given the depth and breadth of the role of the orchestra (as a whole and through its elected representatives) in the overall affairs of the institution, the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra is perhaps the prime example of how far the boundaries of “self governance” can be successfully extended.

The Berlin and Louisiana case studies describe how two institutions, literally worlds and ages apart, have incorporated organizational assumptions and patterns which are quite counter to the traditional North American model. Although there is much to be learned from the principles and practices followed by these institutions, they do not provide a pat formula for changing the traditional North American model. Since its founding, the Institute has taken the position that each symphony organization must decide, within and among the participants of its various constituencies, and with community representation, how it is to be organized and function. In this process, we believe that it is fundamental to develop or affirm a common, shared vision, employing widely inclusive and participative processes. Then, in the pursuit of these goals, a central question to be asked is: “How can we become more effective as an organization, and more satisfying and rewarding, on an enduring basis, to our internal and external constituencies?”

Along these lines, the role of an orchestra’s board of directors in seeking and achieving organizational effectiveness was the topic of a panel presentation during the June 1999 annual meeting of the American Symphony Orchestra League. Joining me in this presentation were Nancy Axelrod, an organizational consultant and founding chief executive of the National Center for Nonprofit Boards and Thomas Witmer, a retired business executive, member of various corporate boards, and of the board of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Tom has been active in Pittsburgh’s organizational improvement program. We think you will find many common threads in these presentations, and we commend them especially to symphony organization board members.

As Tom Witmer noted, “performance excellence” is synonymous with “organizational effectiveness,” and is often denoted “high performance” in the world of commercial organizations. With this in mind, a recently published book addressing the “high performance nonprofit organization” caught our eye, and on page 89, this book is cogently reviewed by Roland Valliere, executive director of the Kansas City Symphony.

Two other pieces complete the primary content of this issue. First, we present a roundtable discussion illuminating the role of the orchestra librarian, one of a number of unique roles within a symphony organization. For this excellent overview, we thank Marcia Farabee, Margo Hodgson, Karen Schnackenberg, Larry Tarlow, and Ron Whitaker. Then, the challenges to and issues to be confronted in “marketing” the modern symphony orchestra and its musical product are outlined by Stephen Belth. After reading these two pieces in sequence, we hope that all participants in symphony orchestra organizations will reflect on the complex, cross-constituency, interactive decision-making processes, based on fully shared information during long lead times, which are required if these organizations are to function optimally.

In the score fragment on our cover, Phillip Huscher once again challenges our knowledge of music and orchestral history. A hint: there are some subtle connections between the cover story and one of the institutions mentioned in this issue. To confirm your knowledge, or to enhance it, see page 86.

On page x, we summarize the latest developments in the Institute’s organizational research and consultation programs. And in the announcements on page vii, we are pleased to welcome Fred Zenone into a more active role with the Institute, and to report other personnel developments, as well as to share other matters of importance to our readers.

Finally, we wish to extend our gratitude to all of the participants in the 146 symphony orchestra organizations which have provided 1999 support to the Institute, as listed on page xi, and especially to the participants in the 44 institutions which provided first-time support in 1999. We are truly appreciative and energized by the growth in interest and commitment to the Institute’s work. As announced at midyear, and as summarized on page 91, we will focus our future publication services toward participants in supporting organizations. Sincere thanks to all involved.

Fred Zenone Becomes Vice Chairman and Active Participant

The Institute is pleased to announce that effective November 1, Frederick Zenone will become an active participant in Institute planning and operations, particularly in the development and execution of our organizational consultation program. In connection with his new role, Fred has been elected Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Symphony Orchestra Institute.

Fred Zenone is perhaps best known throughout the symphony field for his leadership and statesmanship as chairman of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians (ICSOM) between 1980 and 1986, having been an officer starting in 1975. From 1983 to 1989, Fred also served on the board of directors of the American Symphony Orchestra League. He has been an advisor and then member of the board of directors of the Institute since our activation in 1995.

Fred grew up in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and graduated from college in 1957. He then pursued cello studies in New York while teaching in the public schools in Princeton, New Jersey. In 1968, he became a member of the Chamber Symphony of Philadelphia and in the following year joined the National Symphony Orchestra. After 30 years of continuous service as a cellist, Fred retired from the National Symphony Orchestra this past summer.

During his long orchestral career, Fred has been active in a range of organizational and industry pursuits. In the musical area, he was a founding member of the Euterpe Chamber Players and was a lecturer at Georgetown University in the School of Fine Arts. While active with ICSOM, Fred conceived and developed a crisis intervention program and served with executive directors on teams assisting orchestras facing closure. In these and other roles, Fred has been a consultant to a wide range of orchestras. In addition, Fred has been an active musician leader in the National Symphony Orchestra for many years.

In 1992, on the occasion of its 50th anniversary, the American Symphony Orchestra League named Fred one of a distinguished international list of 50 conductors, musicians, trustees, and managers whose work has touched the lives of American orchestras.

Fred lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C., and will carry out his Institute work from that location. He is married to Patricia Larson and they have three children and three grandchildren.

Emily Melton Moves to London

We regret to announce that Program Director Emily Melton has left the Institute to move with her husband to London, to take up residence and to pursue new careers. In her short time with the Institute, Emily made an important contribution to our operating and publishing efforts. The Institute wishes her well in her new home and career.

Alex Bonus and Diana Durkes Join the Staff

In July, the Institute was pleased to welcome Alex Bonus as Administrative/ Program Assistant, and Diana Durkes as Research/Finance Assistant.

Alex Bonus graduated from the Eastman School of Music this past summer, receiving a M. M. degree in performance and literature. In 1997, Alex received his B. M. degree in trumpet performance from Eastman. In addition to his assistant duties at the Institute, Alex hopes to extend his professional development in both instrumental performance and ensemble conducting in the Chicago area.

Diana Durkes has volunteered and worked for a variety of nonprofit organizations. She, and her husband and children, live in a suburb near Evanston.

John David Sterne Joins Board of Advisors

We are pleased to welcome to the Board of Advisors John David Sterne, President and CEO of the Edmonton Symphony, and to thank Mark Jamison for his board service while Executive Director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony.

Serving the Needs of Participants in Supporting Orchestra Organizations

Commencing in 2000, the Institute will focus its publication and other services, including the complimentary distribution of Harmony, on participants in symphony organizations which annually support and encourage the aims and programs of the Institute. Also, Harmony will be delivered by U.S. or Canadian mail to office, home, or other personal addresses.

If you are an orchestra organization participant, please refer to page xi to determine if your organization supports the Institute, and then refer to page 90 which describes our new distribution, support, and subscription program in more detail.

If you did not receive this copy of Harmony at a personal address (see the address box on the back cover), have changed your personal address, or wish to initiate or renew a paid subscription to Harmony, please send us the return postcard inserted before page 1, or contact us.

If you are a participant in a non-supporting symphony organization, or an existing paid subscriber, we would welcome your using the detachable return postcard to request or renew a paid subscription to Harmony for 2000.

Harmony Content On the Institute Web Site

We are now pleased to be archiving on the Institute’s Web site <www.soi.org> the primary content of Harmony, on a 12 month delayed basis, in Adobe Acrobat portable document format (pdf) files. As such, the main Harmony articles can be accessed via the Internet and viewed on computer screens, or downloaded and printed, in their original published form using Adobe Acrobat Reader which, as shown on each Web site page, can be downloaded to your computer at no cost.

Interest Based Bargaining Bibliography

We have recently developed a bibliography on the subject of interest based bargaining (and other synonymous phrases). This listing of references has been posted on our Web site at www.soi.org.

Publication of the Institute’s Financial Results and Condition

On page xiv, we are publishing the Institute’s financial condition as of our most recent fiscal year end, March 31, 1999, and our operating results from our founding through that date. This information is also being posted on our Web site. Henceforth, our fiscal year financial results and condition will be published annually.

Institute E-mail Addresses

In the further use of our Web site, the e-mail addresses of the Institute and its staff are now as follows:

Paul R. Judy, Chairman and Publisher,

Harmony pjudy@soi.org

Fred Zenone, Vice Chairman

fzenone@soi.org

Alex Bonus, Administrative/Program Assistant

abonus@soi.org

Marilyn D. Scholl, Editor, Harmony

publications@soi.org

Diana Durkes, Research/Finance Assistant

ddurkes@soi.org

General Correspondence

information@soi.org

Subscription request or address change

subscription@soi.org

Letters to the Editor

letters@soi.org

Publication questions and manuscript submissions

publications@soi.org

Organizational Consultation and Research Programs

The Institute continues to evaluate how best and more broadly to support and directly assist North American symphony orchestra organizations which seek significant positive change in the ways in which they function. We are considering various ideas and exploring a variety of avenues. Meanwhile, the Institute is continuing to work with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra institutions in customized organizational improvement and development programs.

The Conductor Evaluation Data Analysis Project (CEDAP) is moving along slowly. Recently, with the excellent cooperation of the personnel managers of 16 orchestra organizations included in the CEDAP orchestra universe, the Institute was able to collect the average age and length of service of orchestra members over a 10- year period, which data, along with other orchestral factors, will advance the project analysis. Similar factoral data, generally in the public domain but requiring individual research, is being collected on a range of conductors in the CEDAP universe in order to complete this research project.

Nearing completion is the research into comparative orchestral musician stress and job satisfaction which was initiated by Dr. John Breda under a 1996 doctoral research grant. Publication of the findings of this research is now expected in late November or early December.

EDITOR’S DIGEST

Leadership and Trust

The late 1980s and early 1990s were tumultuous for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, years that included shortened seasons, a reduction in orchestra size, and reduced musician compensation, to say nothing of public bickering.

In 1995, the orchestra’s board chairman asked Joe Goodell, author of the following essay, to serve as interim executive director of the orchestra while the board conducted a search to fill that position. Goodell—whose career was in corporate management, not orchestra management—agreed to do so on a volunteer basis. He had been an orchestra subscriber, but had not previously been involved with the orchestra in any other way. In August 1996, he led negotiations which resulted, without rancor, in a three-year musicians’ contract. He continued to serve until June 1998, when new executive and music directors were appointed. His essay reflects his experiences as both orchestra “outsider” and “insider.”

Of Musicians and Management

The essay begins with a discussion of what Goodell sees as impediments to trust, suggesting that many members of orchestra families contribute to the problem. He posits that to obtain trust, orchestras must have strong management teams. He then outlines a process for assembling such a team, starting with the executive director. His thesis includes calling upon top human resource executives from local corporate supporters to aid in the process, which also includes hiring directors of operations, finance, marketing, and development. And he adds that board chairs should be directly involved in the hiring process for these positions.

In a discussion of “questions of money,” Goodell reminds readers that “the talents required to manage a $10 million orchestra are the same as those required to manage a $10 million business,” arguing that this is not a place to “cheap out.”

Organizational Effectiveness

Because better organizational effectiveness is the goal, Goodell then turns his attention to why a small group to facilitate hiring should be a formal committee of the board. He suggests that this committee can also provide a steadying influence when a senior staff member resigns, when an employee’s subpar performance needs to be discussed, or when an employee needs to be discharged with dignity.

Returning to the “trust” theme, Goodell concludes with the thought that orchestra boards must demand the same standards in hiring leaders of the orchestra that they would in hiring leaders of a business enterprise.

Leadership and Trust

Anumber of American symphony orchestras have struggled with financial problems, rancorous employee relations, and an absence of trust. Discussion about these topics always includes such problems as changes in our culture and the way we spend our individual entertainment funds. But those are not the subjects I propose to address here, except to say that I feel orchestra leadership has failed in many cases to adapt to the changes. We are still trying to manage orchestras as we have in the past, even as the management challenges have become much more difficult, thereby

exposing our management weaknesses. What I do want to discuss are the concepts of leadership and trust.

First a little perspective on my views. Following a full career in corporate management, I agreed in 1995 to serve, on a volunteer basis, as interim executive director of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. As executive director, I managed the orchestra for nearly three years. My observations are primarily of the Group I and Group II orchestras as defined by the American Symphony Orchestra League. (Group I orchestras, about 25, have budgets of $10 million or more. Group II orchestras, also about 25, have budgets ranging from approximately $4 million to $10 million.)

My observations of the Group I orchestras result from interviewing a number of staff members for employment, as well as discussion groups at conferences. My exposure to the Group II orchestras’ management is much broader and deeper.

Some Observations about American Orchestras

It is my observation that orchestra leadership seeks trust from the musicians which is not forthcoming due to poor or marginal leadership itself. Trust flows from honest, candid communications, and the musicians (in this case) must perceive competence in their leaders. In most cases, those leaders (the staff) are insecure, in large part because their backgrounds and training are not appropriate for today’s management challenges. The result is difficult communications, unclear management perceptions of problems and attendant solutions, and attempts to “hide” problems and solutions. Is it any wonder that the staff has great difficulty earning the trust of the musicians?

On the other hand, constant badgering of staff by the musicians, excessive criticism, and making minor problems into major issues doesn’t help foster candid communications either. The musicians cannot earn the trust and respect of the other employees through such tactics.

During my career in manufacturing businesses I observed (with one exception) that enterprises had the labor relations that they deserved. Poor or mediocre management resulted in poor or mediocre labor relations.

Many of us have been involved with organizations that had poor leadership. If we could, we got out of the organization, perhaps after attempting change, with attendant turmoil. If we could not leave the organization, we got frustrated, and I would observe that poor labor relations are almost always based on frustration. Furthermore, I would suggest that the deterioration of the relationship with employees can usually be reversed, but as in all relationships of mistrust, a reversal takes time.

I am often asked how labor relations in orchestras differ from those in industrial unions with which I have worked. Musicians generally have much higher educational levels, and often employ their creativity to see complex conspiracies behind simple actions by staff or board members (a failure in “trust”). The actual union leadership is more difficult to identify in an orchestra, and musicians’ agendas are also hard to pin down. (In a group of 80 musicians, there are probably 100 agendas.) Formal, elected leadership is seldom the real leadership, and the orchestra seems to be more fragmented (with several groups who are not necessarily antagonistic).

I had occasion to spend time with two men who hold senior positions in the musicians’ national union organization. One had been described to me as a “destroyer of orchestras.” I found both men to be reasonable, sensible, and intelligent, with a solid understanding of the issues facing orchestras (as individuals and as a group). Their perspective was not much different from that of most orchestra board members. Their solutions were not as far apart as one might expect. Both men strongly endorsed my observations about the quality of orchestra managements. One noted a significant drop in what he perceived to be the number of strong executive director candidates.

These individuals are employed by the musicians and generally follow their “clients’” directions. Their ability to significantly change the perspectives and beliefs of their “clients” is limited. The union leaders can be strengthened by reasoned presentations, and by records of accomplishment from strong, respected management teams.

Musicians want strong, competent management, capable of clearly explaining issues, not hiding them. They want management whose track record is good, who can recognize their own mistakes, explain the situation to the musicians, and go forward. Many of us have observed incidents that illustrate the antagonism that exists between orchestra leadership on a national basis and the musicians’ union. It’s as though a major part of employee relations is winning “debating points.” Some executive directors seem to think that winning enough points will cause the union to cower or even disappear. The reality is that the union is here to stay. Everyone should be trying to solve problems, not score debating points.

The thread that runs through my analysis is that mutual trust is key to better orchestra labor relations. (The October 1998 issue of Harmony featured three articles that dealt with the need for greater trust: Gideon Toeplitz’s essay on Hoshin and the Pittsburgh Symphony, Paul Judy’s essay on organizational involvement, and a roundtable with members of the Kansas City Symphony family.)

It is my thesis that trust cannot be obtained without a strong, excellent management team. As a group, the orchestras of America can gain this trust, and improve the relations among musicians, staff, and board. Most have a long way to go, particularly in obtaining a strong management team.

Assembling a Management Team

Quite often, board members state that the problem is that the orchestra is not run as a business. I believe that is largely true, but I also believe that, in general, boards fail to pursue this concept. The process of assembling a strong management team must start with the hiring of an executive director. Orchestras should obtain the aid of a top human resource executive from a local corporate supporter. That individual can ensure that the search committee thoroughly understands the candidates. Reference checking should be thorough. (It is amazing how staff members whose performance is marginal or worse move through the orchestras of America.) The human resource executive is accustomed to finding references that are not listed on a résumé, and also knows what questions to ask. An experienced human resource executive will usually recommend a credit check.

Testing for managerial ability is important. But caution is needed with testing. The testing should be proven and not some professor’s toy. It should include an extensive interview with the psychologist managing the testing. The wise human resource executive will not allow the test to become the “go-no go” for hiring. It is part of the mosaic. These tests usually cost around $1,000.

A thoroughly professional hiring process should not stop with the executive director. The directors (sometimes called vice presidents) of operations, finance, marketing, and development should be subjected to the same process, including strong guidance by our now overworked human resource executive. The human resource executive, the board chair, and one or two others should be able to veto the executive director’s choice, and the decision on a candidate to whom an offer is made should be unanimous among them all. Some will argue that such tight control is not proper, that the executive director should be able to “build his or her own team.” But I would argue that the hiring group should insist on quality, even requiring that the search be restarted, if necessary. Because an orchestra staff is small, an “acting” functional director is seldom available, so the strong temptation is to hire the “best we can find quickly.” This is a temptation to resist!

This strong focus on the next level below the executive director is extremely important for the board, and is often a neglected responsibility. In corporate America, even the most senior managers are subject to strong oversight in the selection of key executives. Considering that the executive director has probably not had a great deal of experience hiring people (particularly for orchestras below Group I), the overview is imperative. (Though the personnel manager generally reports to the senior operations executive, that position should also be included in the high-level review process.)

Questions of Money

Salaries are part of the hiring process. The outside human resource executive and the one or two others should help the executive director with salary tradeoffs. Few business executives would disagree with the adage that “you usually get the quality you pay for.” I have seen cases in which an orchestra board has rejected a good candidate because he or she was “too expensive.” Maybe the candidate was worth it! If hiring the right person requires exceeding the budget, so be it. Don’t compound the problem by selecting second best. Board members and others involved with the hiring process must understand that the talents required to manage a $10 million orchestra are the same as those required to manage a $10 million business. The hours are long, weekends are usually not free, vacations are interrupted by calls or faxes. The personnel manager’s job for a Group II orchestra is much tougher than the same job in significantly larger business enterprises. Yet, the orchestra personnel manager is paid 30 to 50 percent less than an industrial counterpart. That manager is the one we rely on as our primary interface with the musicians. Through that interface we want to better communicate with the players and to seek their trust and respect. Is this the place to “cheap out”?

Two additional issues often arise when hiring is at hand. The first is whether to employ a search firm, or rather to “network” and run advertisements in newspapers. On the surface, it appears as though a professional recruiter is more expensive, but the cost must be factored against the length of time it takes to use networks and advertisements. I believe in the use of recruiters, but would caution about recruiters who know the industry too well and rely heavily on friends and their own networks.

The other issue arises when it is necessary to define the ideal candidate. I have concluded that there are only two senior positions that must be filled by candidates who have musical backgrounds: the senior operations executive and the personnel manager. A musical background for the senior marketing position is only a nice plus. The executive director need not be a former musician, but must have a thorough understanding and appreciation of the artistic mission.

Structuring Organizational Effectiveness

In my observations above, I have suggested the formation of a small group to facilitate hiring. I feel strongly that this committee should be a formal committee of the board. It should be chaired by the board chair, or by another board member whose career has involved selecting and evaluating the performance of people. It should include the corporate human resource vice president discussed earlier (whether that person is a board member or not), one or two others, and perhaps even a wise, perceptive musician. This group forms the nucleus of an executive director search committee when required. It oversees the hiring process for the next level of staff (“senior staff”). And the group can function as an informal coaching team to help the executive director deal with people problems. (Selection of members of the committee must be done with care. The executive director must be comfortable and candid when discussing frustrations and people problems.)

Aside from hiring, there are three critical situations in which this committee can make a real difference. The first is dealing with the resignation of a senior staff member (who reports to the executive director). For orchestras with staffs of 30 or fewer members, it is highly unlikely that a successor is in place. It is also unlikely that others in the department can carry the load while a search goes on. The executive director’s tendency is to make a number of phone calls to industry colleagues to find out who “might be available” and perhaps to run an ad in the local newspaper, with the hope of having this position filled in four or five weeks—just shortly after the incumbent disappears.

In this situation, the committee that I propose is called upon to instill patience. It can help the executive director find a temporary solution so that the hiring can be done with care. If a conflict exists between the budget’s provisions for salary and current market conditions, the committee can provide guidance. More than one orchestra has seen its marketing director resign just as ticket sales began. Though the loss may be only one-fourth of the department’s head count, it could be two-thirds of the brain power. The committee I propose would be called upon to help find a solution to the crisis, perhaps by locating “industry” consultants as part- or full-time contractors.

The second area in which this committee can help a great deal is in the identification of individuals whose job performance is lower than acceptable. Many executive directors are not well versed in setting performance standards. The committee would coach the executive director on how to recognize the problem, refuse to work around it, and develop and implement a plan for the poor performer to “get well” (hopefully).

The third critical function of the committee is to temper the trauma of discharging a subpar performer. This involves coaching the executive director in what to say, what not to say, how to preserve the individual’s dignity, and how to determine severance financial parameters. There isn’t a manager in the business world who has not made a hiring mistake. The executive director must understand that such mistakes are normal. The bigger, less forgivable mistake is failure to correct the original one. This committee should also be chartered to oversee the preparation of a staff performance review process and merit salary increases.

The Quest for Mutual Trust

Throughout this analysis is a quest for mutual trust among the board, staff, and musicians. A first-rate staff must be in place before the process of achieving trust can even begin. Only with a strong staff can an orchestra develop effective communications, because it is much easier to talk about communication than it is to implement an effective program.

The most important part of a communication program is that the board chair and the executive director really believe it is important. In too many cases, mere lip service is paid to communications, with little effect.

Of great importance is having the executive director make frequent presentations to the orchestra members on finances and any other issues of interest. These should be carefully prepared and rehearsed presentations. Attendance will be disappointing at first (serving lunch increased attendance at my presentations). A lot of time should be made available for questions and answers. The first year will probably be frustrating. Questions will likely be antagonistic. (“Why do you hire stupid operations people?”) If questions highlight mistakes, admit them! Explain the flaw in the decision process or the incomplete information. Keep secrets to a bare minimum. I believe there are only two areas in which confidentiality is required. One is a musician’s or staff member’s personnel file (salary, medical insurance claims, salary garnishments, etc.). The other relates to fundraising occasions when facts may need to be kept confidential. Anything else is open to the musicians. There may well be information that should not be made public, and this is a defining moment for trust. If you really believe in trust, explain to the committee or musicians why it must be confidential, and then share it. The elected musicians committee will probably want to honor the request for confidentiality.

Having musicians as voting members of the board of directors is controversial. My feeling is that having musicians on the board is part of trust. The musicians must respect board confidentiality, understand board- room decorum (no manifestos to be presented) and the decision-making process (the role of committees), and that the board meeting is not the place to complain about backstage conditions.

No group (board, staff, or musicians) should expect major changes in relationships merely because musicians serve on the board. (“The musicians are on the board. They must know we cannot afford that . . .”) There will be a small positive impact on negotiations for a collective bargaining agreement since financial figures will be familiar (if some of the same individuals that are negotiating are on the board). The staff must realize that making musician leaders (board members, orchestra committee members, and union representatives) aware ahead of time of an announcement of actions to be taken can go a long way toward making their jobs easier. Reduced frustration is a requirement for trust. Trying to undermine certain individuals just doesn’t work. Little time is required to send a few extra copies of announcements ahead of time so that the

Editor’s Digest

“representatives” can deal with questions before the “conspiracy” crowd can organize. There is often a temptation to try to isolate a difficult musician leader. This effort to undermine someone just doesn’t work.

And one final “must.” Communications is not something that gets under way just as negotiations over the collective bargaining agreement begin. It must go on during good times and bad, and the concept must permeate the organization. Front-line operations people will often try to sabotage the effort. They perceive it as a threat to their job security. But that is no excuse for becoming sidetracked.

Concluding Thoughts

In this analysis, I have attempted to share my observations about the weakness of orchestra management (with the qualifications noted earlier where I defined the scope of my observations). The reader should use caution in placing his or her orchestra in the “exceptions” category. A significant part of the orchestra world recognizes that trust and respect are lacking in many relationships among musicians, staff, and board members. There are many possible approaches to changing the trust relationship. Several have been described in past issues of Harmony. None of these processes will work without a strong, competent orchestra management. Once competence is recognized with appropriate communications, trust will replace, in large part, the contentious relationship that characterizes so many orchestras. Change will be apparent, but it will take several years for major changes to be evident.

Longer term, the symphony orchestra “industry” must develop an effective training program. It must be much more comprehensive than the existing intern program. The program should cover a number of years, with periodic followup of short continuing- education courses. There should be exams that measure the individual’s success. “Graduation” should not be automatic. Undoubtedly, other performing arts disciplines would benefit from similar training. Such a program would be costly, but a large foundation should find this to be an opportunity to have a real, near-term, positive impact.

Even absent such a long-term program, orchestra boards must demand the same standards when hiring leaders of the orchestra that they would in a business enterprise. They must not fall into the trap of “too expensive,” and they must insist upon strong oversight of hiring. Trust among the musicians, the staff, and the board can be achieved, but only with a talented staff that is secure and able to instill confidence in the organization.

Joe Goodell is the retired president and C.E.O. of American Brass Company. He holds a B.S. degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an M.B.A. degree from Harvard University.

EDITOR’S DIGEST

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

F or long-time readers of Harmony, the name of this case study’s author, Erin Lehman, will ring a bell. For the first issue of Harmony, Erin prepared an essay on the development of writings about symphony orchestra

organizations since 1960. She has also worked with Harvard colleagues on studies of symphony orchestras in four countries. And for the last several years, her interest has been piqued by the concept of self-governing orches- tras. She shares here her observations of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

How the Orchestra Functions

The Berlin Philharmonic was founded, as a self-governing orchestra, more than a century ago. It is a large orchestra, with 129 members, and has had a roster of legendary conductors. From its beginnings, players have been the shareholders and principal stakeholders.

Lehman explores what this means in terms of day-to-day functioning of the orchestra, from the fact that non-principal players all earn the same pay to the fact that orchestral candidates audition without a screen. She identifies four aspects of orchestra operations as critical to the institution’s ongoing vitality: the self-rostering system employed by each section; the absence of an external personnel manager; players’ rights to participate in smaller ensembles; and players’ exclusive right to choose their own conductor.

She then turns her attention to what makes the Berlin Philharmonic work, concluding that success stems from extensive communication and collabora- tion, particularly among a small group of people. By the time you finish reading this essay, the words Vorstand and Intendant will roll off your tongue.

The Berlin Philharmonic’s world is not without change. Just as the City of Berlin has felt the winds of change over the last several years, so has the orchestra. Sir Simon Rattle has recently been named to succeed Claudio Abbado as chief conductor. The current Intendant has announced plans to leave the orchestra. But Lehman is not worried. She concludes that notions of personal responsibility, artistic self-determination, and the paramount importance of music are the essential hallmarks of the orchestra’s self- governing system.

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

In 1989, I began work with Richard Hackman and Jutta Allmendinger in a study of professional symphony orchestras, designed to explore how orchestras in four countries were structured, supported, and led, and to learn how musicians in these orchestras built their careers. We studied the similarities and differences that existed among professional symphony orchestras in East and West Germany, Great Britain, and the United States (Allmendinger, Hackman, and Lehman, 1996). Much was made of the study’s findings about player job satisfaction (Holland, 1995), but that was not the study’s sole or most important finding. For example, we learned much about the advantages (and disadvantages) of the typical leadership triumvirate commonly found in American orchestras (Judy, 1996). We also learned some things about the funding systems, recruitment practices, and the impact of gender composition on orchestras (Galinsky and Lehman, 1995; Lehman, 1995; and Allmendinger and Hackman, 1995). But the things that piqued my interest were the differences in organizational structures, and, in particular, the concept of a self-governing system. I wanted to find out more about self-governance, and whether and to what degree that made a difference in the musical outcome of an orchestra.

I started to answer my question by taking a closer look at three select orchestras. My colleagues and I studied the London Symphony Orchestra—one of London’s four self-governing orchestras (Lehman and Galinsky, 1994); the Colorado Symphony Orchestra—not a true self-governing orchestra, but still an anomaly in its early partnership model (Lehman, 1997); and Orpheus Chamber Orchestra—a most democratic and conductorless ensemble (Lehman and Lee, 1996). These orchestras revealed the range of self-governing approaches musicians have taken to shape their collective musical lives in ways that harness the power of the group without stultifying the voice of the individual.

But in my view, it is the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra which offers a near- ideal example of a self-governing organization. Unlike the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, the players truly rule. Unlike the London Symphony Orchestra, there is no singular managerial leader who sculpts the orchestra’s strategic direction. And in contrast with Orpheus, there is no external board which exerts the ultimate control. This unique organization is by no means perfect in its design or appeal, but it does suggest an alternative model, in part, if not in whole, for orchestra practice.

I began conducting field and archival research on the Berlin Philharmonic in late 1997. In 1998, I had the good fortune to meet Bernhard Kerres, an associate with Booz-Allen & Hamilton in Munich, Germany. Bernhard and I are working to develop an educational case study seeking to explain the challenges this self- governing orchestra faces in a changing Germany. Much of the material contained in this article is a result of our work on that case.1

Let me offer one last prefatory comment. Some observers have said that the Berlin case is special, and not relevant for the rest of the orchestra field because of this orchestra’s high level of public subsidy and protected status as the premier cultural emissary of Germany. I disagree. Despite its historically preeminent situation, the orchestra is facing the same issues as orchestras around the world—how to augment earned income in an increasingly competitive world marketplace; the precipitous decline of the recording industry; meeting the needs of future audiences. As other orchestras are learning, this one, too, must emerge from its cocoon and become more proactive in shaping its organizational strategy and its destiny. The Berlin Philharmonic is no longer immune to the sociopolitical and economic forces that have swept through German society. For example, following the merger of East and West Berlin, the City of Berlin’s Senate, the prime funder of the Berlin Philharmonic, has been pressed to find ways to make budget cuts in order to meet all the city’s needs. Unlike in the United States, where orchestras depend on unearned income from endowments, individual philanthropy, and corporate sponsorship to balance their budgets, modern Germany has no tradition of largesse, nor does current German tax code facilitate such giving.

A Snapshot of the Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra is one of the world’s fine orchestral ensembles. Founded in 1882 as a self-governing orchestra by a group of musicians who were not pleased with the working conditions they found in the Bilse Orchestra, thisvenerable117-year-oldinstitutionhasarichandcolorfulpast.2 Insurviving every historic milepost of late 19th and 20th century German history, and having had a roster of legendary conductors such as Bülow, Nikisch, Furtwangler, and Karajan, this is an orchestra whose reputation has grown to near mythical proportions.3

Leading orchestras in Germany have larger rosters than their American or British counterparts. The Berlin Philharmonic has 129 members, of whom 3 are concertmasters and another 22 are co-principals. Maintaining a comparatively large roster is intended to keep the members as completely rested and fresh for performance as possible, given the emotionally intense and physically stressful aspects of their work. As one young player described a recent Carnegie Hall performance, “The tremolo in Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony is exceedingly difficult to play. . . . For the violinists and violists it is extremely exhausting. It’s like a marathon. But it’s so much fun! . . . A lot of people like to make music on a tame level—we don’t.”

The Berlin Philharmonic is devoted to the German tradition of music and music making; the majority of players are German citizens. Twenty percent of the members are foreigners and eight percent of the orchestra are women. The first woman, a Swiss violinist, was hired into the orchestra in 1982. Although most of the orchestra’s newly hired players are quite young, they join the ranks with many veterans, some of whom served under Karajan. About the changing complexion of the orchestra, one player said, “I was only about the tenth foreigner when I came into this orchestra in 1986. It was a very German orchestra. Then all of a sudden, about one-third of the orchestra retired in about ten years’ time. Those players were proud of their work together over the past 30 years under Karajan. Now, there are new people coming into a ‘ready-made’ institution.”

The orchestra performs some 100 concerts each year in Berlin alone, as well as throughout the Continent and overseas.4 It operates its own hall, the Philharmonie, located at Potsdamer Platz in central Berlin.

Terms of Employment and Self-Governance

The orchestra was designed from the start as a self-governing entity, meaning that the players were the shareholders and principal stakeholders in the organization. By 1932, the Berlin Philharmonic was operating as a limited liability corporation and the orchestra had been nationalized by its own choice. By 1952, when the German musicians’ union was formed, the players were working under the terms of a conventional master agreement called a Tarifvertrag.

Although the musicians’ union negotiates collective agreements for all orchestras, the Berlin Philharmonic has its own individual agreement. Unlike other German orchestras, in which the number of services is controlled, the Berlin Philharmonic has neither restrictions on hours worked nor any official restrictions on overtime (or requirements for extra pay for overtime). In fact, there is neither a clock nor a clock mentality to be found on the stage of the Philharmonie. The workload can become much more intense than that of leading American orchestras. During the month of April 1999, for example, the Berlin Philharmonic performed 36 services on 22 consecutive days, directly preceded and followed by multiweek international tours.

As with the handful of other self-governing orchestras around the world, such as the London Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna and Israeli Philharmonic Orchestras, equality is essential to the functioning of this musical democracy. Non-principal members of the orchestra all earn the same basic salary. There are no individual negotiations for merit pay. Principal players do earn 25 percent more, and members with families receive higher family allowances as mandated by German labor law. Orchestra members’ average age is 44. Retirement is mandatory at age 65.

Within the master agreement, the orchestra’s bylaws (or Verwaltungsordnung) set forth the rules of governance and enshrine the orchestra’s historic and traditional rights of membership. Three areas of the bylaws are noteworthy.

Those that deal with key personnel:

◆ The orchestra chooses its permanent conductor.

◆ The Intendant (general manager) is appointed by the Minister for Culture on behalf of the City of Berlin, in consultation with the orchestra which must approve the decision.

◆ An orchestral candidate must audition without a screen before the entire orchestra. If he or she receives a simple majority of votes of the orchestra, the candidate is accepted for “Probezeit,” i.e., a probation or trial period. If the permanent conductor attends the audition, he has one vote as well. At the end of this Probezeit, or possibly before that date (there is a maximum of two years allowed for a trial period), the section in which the candidate will play offers a recommendation to the orchestra. After a debate, the entire orchestra then votes by secret ballot on this candidacy for permanent membership in the orchestra. To win membership, the candidate needs a two-thirds majority vote. The permanent conductor has a theoretical veto right, but it has rarely been used.

Those that deal with governing bodies:

◆ The Orchestervorstand (a two-person committee) is elected by the orchestra membership for three-year terms. The Vorstand have the strongest voice in all artistic and administrative decisions and are the official spokespersons for the orchestra membership;

◆ The Fuenferrat is a council of five players also elected from the orchestra membership, with each member serving a three-year term. This council acts as an advisory body to the Vorstand. It might be called on to advise on certain artistic matters, but its main duties are tour arrangements,

auditions, and keeping track of player work data. Although the Vorstand are paid extra for their service, the Fuenferrat are not.

◆ The Personalrat, as with other German companies, is an independent body which oversees personnel and working-condition issues for all employees of the Berlin Philharmonic organization, including the stagehands, technicians, and administrative staff of the Philharmonie hall, as well as the musicians. The Personalrat is an elected committee of seven representatives (serving four-year terms) representing all sectors of the organization. This committee can intervene in, and even veto, many management decisions.

Those that deal with non-governing committees:

◆ The Berliner Philharmoniker (GbR) is a corporate partnership composed of past and present members of the orchestra. The partnership is run by two to three players elected from the orchestra for three-year terms. It is responsible for marketing the orchestra’s performance rights, and for copyrights associated with recording and filming of the Berlin Philharmonic. However, radio income is handled by the Intendant.

◆ The Kamaradschaft plays an important role in the Berlin Philharmonic’s social fabric. Similar to an alumni committee, the Kamaradschaft serves as the principal link between past members of the orchestra and the current organization. Its activities—from obtaining concert tickets for retirees to hosting the annual Christmas party—serves to keep the ties strong and to honor past orchestra members.

Critical Aspects of the Orchestra’s System

Four important aspects of the orchestra’s operations reinforce the vitality of this organizational system and its membership:

◆ the sections’ self-rostering system;

◆ the absence of an external personnel manager;

◆ the chamber music and the Herbert von Karajan Academy; and,

◆ the players’ exclusive right to choose their own conductor.

The string section’s rotation system is governed by no discernible rules or system. Players decide freely among themselves, and often quite spontaneously, where they wish to sit in the section for a given program. All positions, up to and including the first desk, are decided this way. However, the wind, brass, and percussion sections are less flexible, as a higher degree of instrumental specialization is necessary in these groups. But they, too, organize themselves, and independently determine their free time, not needing to seek permission from a “higher” authority. The music director is not allowed to determine seatings. However, the Vorstand bear the formal responsibility for the outcome of these internal rostering and rotation decisions. As frustrating as this may be for conductors, the Berlin Philharmonic maintains a self-rostering system because it further reinforces the concept of artistic self- determination and equality. Every member is considered to be of equal caliber and, therefore, equally capable and interchangeable. The system of rotation keeps the orchestra fully engaged throughout a season.

In contrast to most other orchestras in the world, the Berlin Philharmonic has no personnel manager or similar functionary. Musicians are, for example, individually responsible for adhering to bus, train, or plane schedules when on tour. Missing a connection for whatever reason results simply in the musician having to buy his or her own replacement ticket at his or her own expense. The functions typically performed by the personnel manager in an American orchestra are taken up by the Fuenferrat and the members of the orchestra themselves.5

In addition to their work with the full orchestra, players are permitted to take part in the 26 smaller ensembles which exist independently of the organization, and are allowed to use the Philharmonic’s name if they so choose. These ensembles are autonomous, and range from the famous 12 Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic to the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin and the Philharmonic Wind Quintet. There are also opportunities for teaching, and many players give private lessons. Some players hold teaching professorships at local music schools, and some are faculty of the orchestra’s own Herbert von Karajan Academy, a separate legal entity founded by its namesake. This is a small enterprise to which selected, promising young musicians from around the world come to study as fellows for a period of two years. These musicians gain training through private lessons, primarily with principal players of the Berlin Philharmonic, and through opportunities to perform with the orchestra when substitutes are needed. In this way, the orchestra develops new candidates for its own ranks, and several current members of the orchestra are alumni of the Academy.

Arguably, the most important feature of this orchestra is the right of the players to choose their own chief conductor. Few other orchestras in the world allow musicians this authority. This right is expressly stated in the bylaws, and is a principal tenet of the organization. Technically speaking, the musicians did not select Bülow, Nikisch, or Furtwangler. Those individuals were proposed by

the Wolff Concert Agency, and the orchestra simply ratified their appointments. Karajan, although also approved by the orchestra, had been waiting in the wings. Certainly, those conductors had the confidence and vote of the players. But, to be more precise, in 1989, Claudio Abbado was the first permanent conductor actually to be elected by the orchestra membership, following a selection process designed and carried out solely by the orchestra members. When the vote was taken, players had to be present (no proxies were allowed) and a two-thirds majority was required. At that time, there was much debate among players as to the leader they wanted—and should have—on the podium, and the ramifications of their choice.

In 1999, the considerations were even more significant. As much as Claudio Abbado was celebrated for his work with the orchestra, his plan to leave in 2002 represents a turning point. Abbado has been described as a living link to the past, the Romantic era. The orchestra faced the decision of whether to replace him with an older, established conductor—linking to that tradition—or to find a new, perhaps younger, but potential powerhouse.6 As much as the choice was a monumental issue for the orchestra, it was also significant for the next music director. Said one veteran player:

This is a strange beast. We are an obstreperous bunch. Think about it: we elect our own music director democratically and then give him enormous authority. But we may also fight him along the way. We are fiercely independent, but we tolerate our conductors. How can they (music directors) live with this? Not all conductors can deal with this. It’s like the Roman consuls. They were given dictatorial power for two years and then they were out. Not many conductors can handle this duality/dichotomy.

Leadership and Leadership Relationships

There are a number of constituencies that both formally and informally influence one aspect or another of the Berlin Philharmonic’s operation—from external forces, such as local politicians and German labor law, to the internal committee structure and the full orchestra itself. For example, the Minister for Culture not only conveys the annual appropriation from the City of Berlin’s Senate, but also its wishes and concerns. These might include such items as who they would like to see as Intendant or even chief conductor, and the level of domestic touring in Germany. Then there is the Personalrat, mandated by German labor law, which can intercede in anything having to do with workplace conditions, and even on some administrative decisions. Orchestra members, in addition to selecting their own conductor and their fellow players, also select and vote on candidates for Intendant. This choice, as that of the chief conductor, must have the consent of the Senate, through the Minister of Culture who finalizes the contracts, because both the chief conductor and the Intendant are employed and paid by the Senate, as are members of the orchestra.

To be sure, the organization’s leadership is vested first and foremost in the Vorstand, and then further through the Intendant and chief conductor. The chief conductor is expected to set the musical direction for the organization by designing a compelling artistic approach for the orchestra. He suggests what repertoire he will perform in the 30 percent of the season’s programs he leads, as well as which guest conductors and solo artists should be invited during a particular season. It is up to the Intendant then to work out these arrangements. The Intendant’s role is fundamentally one of coordination and implementation. He also has responsibility for the organization’s administration and financial operations, and deals with the Minister for Culture on matters having to do with the annual budget and quarterly accounting.7 TheVorstandmustbefullyapprisedofandcaninterveneinallof these areas at any time. For example, the conductor seeks agreement with the Vorstand about his artistic plan, including guest conductors, soloists, repertoire, and even touring; the Vorstand discuss with all conductors (chief and guest) the number of rehearsals that will be needed (or should be used); together with the conductor and/or Berliner Philharmoniker, the Vorstand approve recording projects; and they are informed of important budgetary concerns.

Communication and Collaboration

In the final analysis, the operational success of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra turns on the relationships among three to four people who must be in constant contact and agreement with one another. The bylaws of the organization make it self-governing, but its leadership in action is based on the notion of “Mitbestimmung” or co-determination. The present Intendant said, “It is a fascinating subject because it works so well. As long as everything goes well, there is no question about this form of governance.” The Intendant had a long and productive working relationship with Claudio Abbado before coming to the

Berlin Philharmonic. And he feels a collegiality with the two Vorstand. “They often solve [internal orchestral] problems themselves although they keep me informed. And I am always presenting my ideas for consideration.” In fact, the Intendant and the Vorstand find themselves in constant communication—either face-to-face during rehearsal breaks backstage, in the Philharmonic’s offices, or by cell phone at all hours of the day or night. According to the Intendant, the rules of their working relationship are not formalized. For him, the relationship is akin to what sociologists call symbolic interaction: “You create rules by the actions you take.” One former Vorstand reinforced this notion: “You need two things: good people and you need the rules. But the best is when it works without rules!” The working relationships and balance among these key individuals are critical for the organization. The orchestra, too, is concerned that the organization’s leaders are all focused on the long-term health of the institution. Right now, there is a clear and mutual understanding about what needs to be done.8

One important characteristic of a good Vorstand, according to one, is that “he have his ear in the orchestra,” meaning a Vorstand must know what the orchestra is thinking; to be in touch with the other orchestra members. But each Vorstand has the five members of the Fuenferrat to help in this regard. The Fuenferrat are important in the leadership structure because they extend the Vorstand’s ability to reach and even poll the entire orchestra when need be, and they manage details for which the Vorstand do not have time. Communication is further facilitated by full orchestra meetings which are typically held on a bimonthly basis, or as needed. With all the impending decisions in 1999, the orchestra met monthly. Vetting important orchestra decisions is a key operating principle of the organization, but often there are sensitive issues that cannot be shared with the full orchestra. Some members are concerned by the potential for “a lack of transparency” in organizational decision making. And yet, to the Vorstand, this is a necessity. As one of them said, “Everything is transparent, except for the secrets.”

Other important characteristics of the Vorstand are the ability to think strategically, to plan ahead, to take responsibility, and to have “strong nerves” for the tremendous demands placed on them (there is no reduction in orchestra services nor generous compensation for taking the Vorstand position). Burnout is a hazard. As a former Vorstand described it, “This job needs a lot of time. It’s very hard. You’re always working. And you can’t afford to be everyone’s friend: not between the conductor and the orchestra, and not between orchestra members.” About his experience, he said, “We were involved with the Intendant all the time. We were always together talking and deciding things. We were not so involved with the budget. That’s the Intendant’s responsibility, but we certainly know what problems there are. The role is like one of a judge. You are always having to find compromise—and then having to explain that to the orchestra.”

Cultivating Participation

Cultivating member participation is a vital part of this democratic organization. Responding to a question about how players are developed into future leaders, a former Vorstand said, “Now there is a big generation change in the orchestra. Over the last 10 years, we have hired 60 new members and most of them are younger. They will need more time within the orchestra before they become interested and before they can become good orchestra leaders.” In fact, the orchestra requires that players be members of the orchestra for at least five years before they can run for election. (This has been reduced from a ten-year minimum). To be nominated, a candidate needs just five player signatures. Still, participation is always an issue. Often there is only one candidate for a vacant post, yet an election must still be held. For example, October 1998 was the triennial election of the Vorstand. Only the current Vorstand indicated their interest in running for the two posts. In light of this, and concerned for the health of the process, one of them initially stepped aside and encouraged two other players to run. However, the present Vorstand won the necessary majority votes.

About this experience, the younger of the two candidates who were not elected said: “I felt a little young to be doing this, but on the other hand, I had ideas—like transforming the Philharmonie hall into a more dynamic place to attract people to Potsdamer Platz. We need restaurants and more modern marketing. The problem with the election is that there is no way to really share your ideas. The vote is based mostly on personal reputation.” In the end, this player was glad he was not elected, but he was still very concerned about his orchestra and its situation: “Politically, we’re all dilettantes and we’re not professional managers, but the goal is to maintain this musical environment—because it’s what brings out our best.” The other candidate, an orchestra veteran, was also rather relieved. “I am a free man!”

Nevertheless, he was also concerned about the issues at hand for the orchestra and its future. As he said, “The orchestra is somewhat unsettled now. There is the impending change in conductorship. We are very concerned about our compensation. We work extremely hard. But we do it for the music. This is why you join the orchestra.”

Despite impending changes within the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra organization, players appreciate their special brand of music making. Most players would agreed that they are “a bunch of strong-minded individuals.” As one young member put it, “We are spiritual brethren here. We all see music the same way! It’s great when you have like-minded people to work with. We don’t know much about management. And this orchestra may not be for everyone, but it’s great for us!” A former Vorstand reinforced the point with a wry smile, “You know good people often have strong personalities. Sometimes it would be easier to have people who would just go along. But all we need is a majority and the other 49 percent can be upset. This is a democracy.”

“The Philharmonic Spirit”: An Outgrowth of

Organizational Structure

In addition to having an impressive roster of permanent and guest conductors, the Berlin Philharmonic has worked with the greatest composers and solo artists of the day—from Richard Strauss in the 1890s to Paul Hindemith in the 1950s and Hans Werner Henze in the 1990s, and from famed violinist Yehudi Menuhin in the 1920s to Anne-Sophie Mutter in the 1990s. But perhaps most importantly, the orchestra itself is composed of some of the finest musicians in the world. Each is of soloist caliber, and many are showcased in the orchestra’s own concerts. Arguably, the orchestra’s most distinguishing marks are not only the tremendous talent of its members, but also the high standard they set for themselves—and to which they adhere from generation to generation. To be a “Philharmoniker” has always been considered by many a great accomplishment, and similar to membership in an exclusive club. Moreover, it is often said that the Berlin Philharmonic has a certain, special spirit, a “Philharmonischer Geist,” an unparalleled “esprit du corps.” The essence of that Philharmonic spirit comes from two sources: its legal and operating structure, and its few, but inviolate, group norms.

Remarkably, the special spirit of the Berlin Philharmonic is passed on and imbues each player. This is apparent during performances when all members evidence a deep sense of responsibility for the outcome of the concert. It is an individual’s personal

responsibility to rise to the occasion and deliver his or her best performance. Orchestra members don’t count on an external agent to make this happen, or to be used as excuse for a poor performance. As one former Intendant said, “The orchestra would never sink below a certain level, for their pride would not allow it. If conditions are unfavorable, if a guest conductor lacks the power to inspire them, or cannot establish real [contact] with the orchestra, it will do anything it can on its own to guarantee a good performance. . . . It is an orchestra that intellectually participates in the solution of difficult passages, individual problems of intonation, and questions of ensemble.”9

Closing Thoughts

These notions of personal responsibility, artistic self-determination, and the paramount importance of the music itself are the essential hallmarks of the Berlin Philharmonic’s self-governing system. In this author’s view, these ideas begin to explain the difference between orchestra organizations whose overall performance is “clearly outstanding” versus those which are “average or typical.” Rarely, among the hundreds of musicians I have interviewed in the past 10 years, have I heard the resounding comments that are captured below. Resources and historical and political circumstances notwithstanding, there are lessons to be learned from the kind of enthusiasm and commitment that the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra system fosters. Indeed, it is palpable.

“This evening will be a great performance. Because people give everything. It’s a natural thing, too. Everyone pulls for the best. Because we’re treated very well and when you’re treated well, you feel special and you want to do well. You also think to yourself, this is the Berlin Philharmonic! You can’t let any slip-ups happen.”

“This is the second time this week that I’ve played Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and I still get very excited and on the edge of my seat about it. Why? If we let our standard go down, it goes quickly. The more comfortable you get around people, the more comfortable it gets. But sometimes, it’s very uncomfortable—especially if you don’t know your part, for example. Then people (fellow players) make comments indirectly and it hurts. It has the intended effect.”

“If I died and came back to life, I’d still want to be a musician in this orchestra. To be a soloist is glamorous, but lonely. Here, we are part of a big family.”

“We have a huge, wide-ranging repertoire, and in the 1970s, we would do four to five different programs on each tour. Karajan would only rehearse the key or tough parts and leave the rest for performance. That created a great deal of tension. I remember having a record player in my hotel room—rehearsing and sweating! We never played a complete piece in rehearsal! In fact, we sometimes would ask Karajan for more rehearsal time!”

“Who motivates me? Each player on each side of me. They are superb musicians and so they encourage me. You want to do well.”

“Every one of these players is of soloist quality. In fact, many of us had to make the hard choice of whether to stay principal in another orchestra or come here as a section player. As an example, there might be 17 other good bowing ideas besides the concertmaster’s, but we have all subjugated ourselves to the greater whole—the orchestra—and the music. We don’t allow our individual agendas to take precedence or get in the way. When that happens, the group will rein in an errant player.”

“For other orchestral players, their work is nine o’clock to five o’clock, and then there is private or family life. For us, this is our life. We have all committed completely to it.”

I would like to thank several people for their support of this project, especially Fergus McWilliam, Elmar Weingarten, Peter Reigelbauer, Christhard Gössling, Hellmut Stern, and Paul Judy.

Erin V. Lehman is a research coordinator in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. She holds a B.A. degree from Wellesley College, and is a Ph.D. candidate in arts policy and management at City University, London, England.

References

Allmendinger, Jutta, and J. Richard Hackman. 1995. The More, the Better? A Four-nation Study of the Inclusion of Women in Symphony Orchestras. Social Forces 74: 423-460.

Allmendinger, Jutta, J. Richard Hackman, and Erin V. Lehman. 1996. Life and Work in Symphony Orchestras. The Musical Quarterly 80 (2): 194-219.

Galinsky, Adam, and Erin V. Lehman. 1995. Emergence, Divergence, Convergence: Three Models of Symphony Orchestras at the Crossroads. The European Journal of Cultural Policy 2 (1): 117-139.

Holland, Bernhard. 1995. A Pathetic Living at the Symphony? New York Times, November 5, sec. 2, p. 1.

Judy, Paul. 1996. Life and Work in Symphony Orchestras: An Interview with J. Richard Hackman. Harmony 2: 1-8.

Lehman, Erin V., and Adam Galinsky. 1994. The London Symphony Orchestra. Case No. N9-494-034. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Co.

Lehman, Erin V. 1995. Recruitment Practices in American and British Symphony Orchestras: Contrasts and Consequences. Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society 24: 325-343.

Lehman, Erin V., and Fiona Lee. 1996. Determinants of Organizational Effectiveness: The Case of Chamber Orchestras. An unpublished study of Orpheus, Metamorphosen, and Pro Arte Chamber orchestras.

Lehman, Erin V. 1997. Is the Glass Half-empty or Half-full: The Colorado Symphony Orchestra, 1990-91 to 1996-97. A report to the Colorado Symphony Orchestra board of trustees. Updated and available at <www.arts.endow.gov/pub/lessons/casestudies/colorado.html>.

Notes:

1 I would like to express my thanks to the Symphony Orchestra Institute which has, in part, funded this research. The case will be available through the Harvard University Kennedy School of Government case collection, which can be accessed at <www.ksg.harvard.edu>.

2 At the time of the orchestra’s founding in 1882, Berlin was just developing as the capital of the Wilhelmine German Empire. Given this fact, the radical nature of the musicians’ decision to start their own enterprise cannot be overstated. By deigning to form a democratic organization in a most unrepublican period in world history, the orchestra had created an anomaly. Moreover, as with many entrepreneurial undertakings, the newly formed “Philharmonic Orchestra (formerly Bilse Orchestra),” as they called themselves, was not free from strife. “It staggered from one crisis to another and one never knew if it would survive.” But in time, and with the instrumental help of a local impresario, Hermann Wolff, and his wife Louisa, the orchestra found success. It was Wolff’s concert agency that was responsible not only for helping the nascent ensemble with concert dates, but also for discovering conductors for the group, and soliciting private contributions to help the “Philharmonic ship” stay afloat. Except for a brief period when a Philharmonic Society was established to generate dues and donations, the Philharmonic Orchestra depended on ticket sales and tours to make ends meet (Stresemann, 1979).

3 Herbert von Karajan, who long coveted Furtwangler’s post at the Philharmonic, was the orchestra’s fourth permanent conductor, serving from 1954-1989. Given his tenure, it is hard to encapsulate in just a few words the lengthy and legendary “marriage” between Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (volumes have been written about the man and the subject). One thing was indisputable, however: Karajan brought the orchestra to a level of artistic excellence, fame, and fortune-—especially in their early partnership—that few other orchestras could ever rival. They had critical acclaim, hundreds of recordings, films, TV broadcasts, international tours, the Salzburg Easter and Summer Festivals, the Pfingsten and Berlin Festivals, and increasingly generous incomes.

4 For more information about the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, visit their Web site at <www.berlin-philharmonic.com>.