Bitcoin and Proust or “À la recherche de l’argent perdu”

We have probably all come across that word BITCOIN and not given it much thought. Or perhaps we have. It’s pretty interesting as a modern financial phenomenon. My take on it is that it was created as a reaction against government and centralized monetary structures as a result of the financial collapse in 2008. It appears to be a million miles away from the basic definition of money as being a store of value and yet it shares many of the same characteristics as normal money in its electronic form. It is a currency with no centralized repository, based exclusively on an internet platform and founded on peer to peer transactions without any intermediary. In essence it is virtual money and the idea is only kept in existence by the belief and faith and dreams of those who want it to work.

We have probably all come across that word BITCOIN and not given it much thought. Or perhaps we have. It’s pretty interesting as a modern financial phenomenon. My take on it is that it was created as a reaction against government and centralized monetary structures as a result of the financial collapse in 2008. It appears to be a million miles away from the basic definition of money as being a store of value and yet it shares many of the same characteristics as normal money in its electronic form. It is a currency with no centralized repository, based exclusively on an internet platform and founded on peer to peer transactions without any intermediary. In essence it is virtual money and the idea is only kept in existence by the belief and faith and dreams of those who want it to work.

You could actually use this description to define money anyway. Money per se–that is, the stuff you put in your wallets and purses–is fast becoming extinct. We rely upon cards and electronic transactions, which we don’t really understand but nevertheless have the faith and the dreams to make work. And sometimes, like back in 2008, they don’t work. We never see our wealth. There isn’t a strong room at Fidelity or your Bank, for instance, where you could go and look at the dollars that belong to you. When you buy a house, probably the biggest transaction in our lives, it’s down to just a question of shuffling papers and wire transfers, but we never have a visceral experience of money actually changing hands. It’s all done by those mysterious people from the Bank and your attorney and realtor who magically make it all happen. But are you really in the drivers seat? Or are those plastic cards we carry around making us unintentional debtors? This is the world we have created and it is fast, convenient and a wonderfully strange and inventive manifestation of how we see the world.

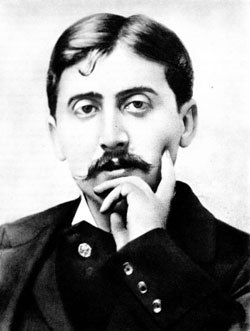

So how does this impact Proust the great French writer who died in Paris in 1922 at the age of 51. He is best known for his masterpiece, “À la recherche du temps perdu” or “In Search of Lost Time” which over the course of 2000 plus pages and seven volumes presents us with a monumental reexamination of his life. Proust reinvented his life and to understand him you need to be part of this reinvention. His days were spent upside down. He slept during the days and emerged at night. He was an aesthete who adored art and music and some might describe him as an introverted version of Oscar Wilde. But that only gives a mild flavor of the originality of the man as a writer and thinker. His writing is the equivalent of slow food. There is no instant gratification. You can’t pick up his books and just plow in. You have to enter and change, breathe differently, modify your expectations and the way you think of time, and fall into his world, which will then open up its astonishing riches. Music was a passion for him and is a recurrent theme in “In Search of Lost Time.” He was intoxicated by music, attended many concerts, was familiar with many of the great composers of the day and thought of music as a central theme in his life and writing.

So how does this impact Proust the great French writer who died in Paris in 1922 at the age of 51. He is best known for his masterpiece, “À la recherche du temps perdu” or “In Search of Lost Time” which over the course of 2000 plus pages and seven volumes presents us with a monumental reexamination of his life. Proust reinvented his life and to understand him you need to be part of this reinvention. His days were spent upside down. He slept during the days and emerged at night. He was an aesthete who adored art and music and some might describe him as an introverted version of Oscar Wilde. But that only gives a mild flavor of the originality of the man as a writer and thinker. His writing is the equivalent of slow food. There is no instant gratification. You can’t pick up his books and just plow in. You have to enter and change, breathe differently, modify your expectations and the way you think of time, and fall into his world, which will then open up its astonishing riches. Music was a passion for him and is a recurrent theme in “In Search of Lost Time.” He was intoxicated by music, attended many concerts, was familiar with many of the great composers of the day and thought of music as a central theme in his life and writing.

“As the title of Proust’s life’s work – ‘In Search of Lost Time’ – suggests, time is the central preoccupation here: time lost, time regained, time needed, time elapsed, remembered, lived and experienced. So many facets and transformations of the concept of time have never before been explored in literature. But it is music, the most temporal among the arts, that is the mistress of Time. Music is the one that spins, halts and stretches the wheels of time in Proust’s novels and serves as a guiding thread for the Narrator of Proust’s 7-part novel on his journey towards artistic revelation.” –Katarina Markovic, New England Conservatory musicologist.

There is the most amazing paragraph that Proust writes as he thinks about a concert he has just attended and which moved him greatly. It is contemplation on music and language and a fantastical leap to a conclusion on both:

“I was truly like an angel who, fallen from the inebriating bliss of paradise, subsides into the most humdrum reality. And, just as certain creatures are the last surviving testimony to a form of life which nature has discarded, I wondered whether music might not be the unique example of what might have been – if the invention of language, the formation of words, the analysis of ideas had not intervened – the means of communication between souls. It is like a possibility that has come to nothing; humanity has developed along other lines, those of spoken and written language. But this return to the unanalyzed was so intoxicating that, on emerging from that paradise, contact with more or less intelligent people seemed to me of an extraordinary insignificance.”

What he is saying here is to reimagine the way we communicate, the way our world has decided upon its priorities. He is dangling that seductive and mesmerizing view that there is an alternative that we could have considered and a path that we could have followed. This path could have given us something even better, “the means of communication between souls.” Bitcoin can be compared to Proust in exactly the same way. It is providing us with an alternative far from government and central banks, and based upon a leap of imagination into a new world of thinking about the construct that we call money. The great French writer and essayist Michel de Montaigne back in the late C16 would have approved: “We have been right to make much of the powers of our imaginations, for all our goods exist only in dreams.”

Yaval Noah Harai in his recent best seller “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” writes:

” What makes humans different from other animals is not reasoning, tool-making or the capacity for morality, all of which are found to some degree among other animals. Humans are different because they inhabit an imagined world, created from their own ideas, myths and fantasies, which they take as real.”

This is very much along the lines of Prospero in the “Tempest”………”We are such stuff as dreams are made on.” It was in 2008, the year of the collapse, that Satoshi Nakamoto (who may or may not exist or may be a pseudonym) tried to invent a new god and myth with Bitcoin. I can only assume that he was not reading Proust or Shakespeare or Montaigne to arrive at his deregulated decentralized reinvention. He was looking at markets and entrepreneurial opportunity to create his master plan and it certainly worked for a time, but in 2014 it was rated the worse performing currency of the year. So the belief is beginning to fall away. (And, ominously, there have been recent news articles suggesting that terrorist organizations like ISIS could use Bitcoin to raise funds for their activities.)

Nevertheless, the idea is sheer Proustian in its alternative logic and shares the main features of Harai’s description “humans are different because they inhabit an imagined world.”

Money has the value we impose upon it and this becomes central to our polity. Money in essence is about utility. Art is about something else entirely. Oscar Wilde said that “art is useless”, in that it has no utility and yet it is central to our “humanness” as perhaps its most central element. Art can’t be used in a utilitarian way, and yet despite its “uselessness” we cannot as a species prevent ourselves from being fascinated and passionate about its creative transformative heart beat which does indeed speak to our souls as part of our imagined world.

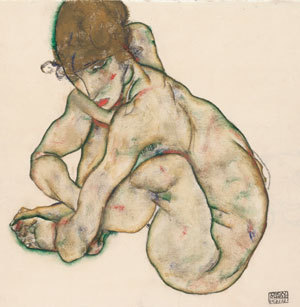

Art has been seen by some as our response to nature, nature with all its beauty, ugliness, power, terror, sublimity, originality, and perversity. And we really can’t stop ourselves from this connection with art. That’s why we look with awe at cave paintings from 35,000 years ago which join us with the earliest and yet so recognizable forms of human thought and experience, or listen to Beethoven or gaze at the shockingly crude ugliness of Egon Schiele’s nudes (in photo right) and know that we are there too. It’s our lives and our fantastic world that are being described and laid bare. Beethoven has no utility nor does Michelangelo, Hendrix, Billie Holiday or even Cervantes “Don Quixote.”. And yet art contains the basic values that make our lives worth living. Art is more than a quiet balm. Art gives us some perspective on the infinite and delivers us to a different place from the one where Bitcoin beckons. We leave our quotidian lives and selves and enter the possibility of exploring other worlds by reading Proust and many others, with as much energy and commitment as perhaps we squander on other paradises.

Art has been seen by some as our response to nature, nature with all its beauty, ugliness, power, terror, sublimity, originality, and perversity. And we really can’t stop ourselves from this connection with art. That’s why we look with awe at cave paintings from 35,000 years ago which join us with the earliest and yet so recognizable forms of human thought and experience, or listen to Beethoven or gaze at the shockingly crude ugliness of Egon Schiele’s nudes (in photo right) and know that we are there too. It’s our lives and our fantastic world that are being described and laid bare. Beethoven has no utility nor does Michelangelo, Hendrix, Billie Holiday or even Cervantes “Don Quixote.”. And yet art contains the basic values that make our lives worth living. Art is more than a quiet balm. Art gives us some perspective on the infinite and delivers us to a different place from the one where Bitcoin beckons. We leave our quotidian lives and selves and enter the possibility of exploring other worlds by reading Proust and many others, with as much energy and commitment as perhaps we squander on other paradises.

“I hardly know whether it would not have been better for the human race if this swift movement of thought, this acumen, this cleverness, which we call reason, had not been given to man at all, since it is a plague to many and salutary to a few, rather than given so abundantly and so lavishly.”–Cicero

No comments yet.

Add your comment