Beethoven Symphony Basics at ESM

Beethoven’s Classical Inheritance: the Symphony and the Orchestra

The Symphony in the Late Eighteenth Century

Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792, and completed his First Symphony in 1800. Exploring Beethoven’s genius in the symphonic genre requires an understanding of the genre which Beethoven inherited. What was the symphony in the late eighteenth century, as understood by Beethoven? There are many models of works that can shed light on this, and theorists and critics of the day have also left many contemporary descriptions of what “symphony” meant in the years leading up to Beethoven’s first symphonic composition. These descriptions tend to agree on three common characteristics: 1) it is a work for instruments, most commonly the string-centric ensemble we now call orchestra, 2) it functions as a dramatic work within different performance settings, and 3) its dramatic content fits into specific expectations about musical structure.

One of the most complete descriptions of the symphony during this time was J. A. P. Schulz’s entry “Symphonie” in the 1774 edition of Johann Georg Sulzer’s influential multi-volume dictionary Allgemeine Theorie der Schönen (General Theory of the Fine Arts), which continued to be revised and reissued until 1798. Bathia Churgin’s 1980 translation of Schulz’s complete “Symphonie” entry, with a fine commentary, can be read here, but select portions of Schulz’s description in Churgin’s translation will serve as starting points for highlighting and clarifying the three characteristics identified above.

1. A symphony is an instrumental work, generally for orchestra.

“The instruments that belong to the symphony are violins, violas, and bass instruments; each part is strongly reinforced. Horns, oboes, and flutes can be used in addition for filling out or strengthening.”

Schulz’s description is consistent with a gradual standardization of orchestral instruments that emerged in the first two-thirds of the eighteenth century. The pervasive Italian influence early in the century established a four-part string texture consisting of violin 1, violin 2, viola, and basso which would include cello and double bass (violone), possibly a bassoon, and an instrument that could play chords such as a harpsichord or organ. To this four-part string texture could be added two oboe parts and two horn parts for tone-color and dramatic variety, resulting in what was sometimes referred to as the “Orchestra of 8” (four string parts, four wind parts). At times, oboes could be replaced by flutes, or less often, a flute or two might join the winds. Schulz does not mention that for more celebratory occasions two trumpets and timpani could also be added to the Orchestra of 8, resulting in an “Orchestra of 11” (four string parts, four wind parts, two trumpet parts, one timpani part). Schulz is careful to distinguish that only the string parts were “strongly reinforced” by having multiple players on each part; winds were generally one to a part. By the late 1770s, symphony composers regularly expanded the wind colors of the orchestra, reflecting the influence of the court Harmonie—wind ensemble—the core of which included two oboes, two horns, and two bassoons, but could have other wind instruments such as flutes and clarinets added or replacing the oboes. By Beethoven’s day, the winds in symphonies included two each of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, and trumpet, along with timpani. More details on the development of the orchestra, and the specific instruments of Beethoven’s day, appear in the “Beethoven’s Orchestra” essay below.

2. A symphony is a dramatic work, functioning differently depending on the performance setting.

“The symphony is excellently suited for the expression of the grand, the festive, and the noble. Its purpose is to prepare the listeners for an important musical work, or in a chamber concert to summon up all the splendor of instrumental music. If it is to satisfy this aim completely and be a closely bound part of the opera or church music that it precedes, then besides being the expression of the grand and festive, it must have an additional quality that puts the listeners in the frame of mind required by the piece to come, and it must distinguish itself through the style of composition that makes it appropriate for the church or the theater. . . .[It] is often of pleasant, pathetic, or sad expression.”

Schulz emphasizes that a symphony functions as dramatic music, whether to prepare an audience for a subsequent theatrical work (opera, oratorio, play) or liturgical piece, or as a self-standing “chamber symphony.” This indeed reflects a prevailing eighteenth-century tripartite stylistic division of music functioning in the Theater, the Church, or as Chamber music—by Beethoven’s day the independent “chamber symphony” had become the prevailing model—but in all cases a symphony is to convey a dramatic experience. The sound of the music itself was certainly capable of guiding the listeners’ thoughts through various emotions, places, and states of being, and during the eighteenth century more specific dramatic topics (topoi) became commonplace in symphonic language. A topic (topos) is created by using a series of musical characteristics such as meters, tempos, keys, rhythms, melodic shapes, motivic and ornamental gestures, and instrumentation, to take the listener to a place or emotional state, i.e. a dramatic scene or situation. Such meaning was generated by the use of musical ideas over and over again in similar theatrical settings, thus becoming recognized or conventionalized as associated with these settings, and by imitation of natural or recognizable things in what artistic theorists referred to as mimesis. The specificity of topical dramatization in symphonies became so clear that composers began identifying pieces of literature, historic events, and other recognizable extra-musical occasions with their symphonies. By 1800, music encyclopedias began to include the genre “Characteristic Symphony” as a category of symphony directly related to a specific extra-musical inspiration identified by the composer.

Here is a list (not exhaustive) of some of the more common topoi found in late eighteenth-century symphonies, many related to the states Schulz mentions in the quote above and in other places throughout his symphony description. Links to orchestral works with which Beethoven likely would have been familiar exemplify each topos:

Brilliant: flashy, showy, fast notes in faster tempos, often associated with Comedy. Haydn, Symphony No. 60 in C “Il distratto,” finale.

C-Major (fanfare) style: majestic, celebratory, fanfares, dotted rhythms, triadic themes, use of trumpets and timpani. Opening of Mozart, Symphony No. 41 in C “Jupiter” (0:00-0:47).

Galant or Courtly: Quaint, often relaxed, yet some sophistication of harmony and melody, predictable phrase lengths (multiples of four). Most often associated with the minuet (moderate triple meter) and simple andante march. Haydn, Symphony No. 88 in G, mvt. 3.

Hunt (Le Chasse): usually very fast compound meter (6/8), often polyphonic, with quick eighth-note horn call passages in horns or oboes. Found often in finale movements. Haydn, Symphony No. 73 in D, finale.

Janissary (Turkish): tactfully used to represent “the other” i.e. peoples from the Ottoman Empire, or battle and armies. Drones, very static harmony, highly repetitions melodic patterns reflecting minor or modal scales usually played by oboe, clarinet (basset horn) or piccolo, uneven or unusual phrase lengths (7 bars, 11 bars, or a 4- or 8- or 12-bar phrase with a 2-measure “tag” on the end), instrumentation sometimes includes trumpets, piccolos, contrabassoon, and a variety of percussion instruments (bass drum, cymbals, triangle). Most often in C major or C minor. Mozart, Overture to Abduction from the Seraglio, opening section (0:00-1:35).

Majestic: similar to C-major. Dotted rhythms, slow or moderate tempo, duple or quadruple meter, march-like, related to French overture. Often slow introductions to first movements. Opening of Haydn, Symphony No. 104 in D “London” (0:00-2:23).

Pastoral: associated with shepherds, love, and repose. Slow, soft, specific key relationships, often relaxed triplet accompaniment, woodwinds featured, particularly oboes and flutes, some slow soft horn calls, slow harmonic motion, simple, lyrical melodic ideas often set as duets (imitation of operatic love arias or duets). Haydn, Symphony No. 7 in C “Le midi,” mvt. 2 (10:29-16:60).

Rustic: varying degrees of culturally “low” music. Simple steady harmonies, simple repetitious melodies, drones, moderate triple meter (3/4 Ländler), fast duple meters (2/4 contredanse) or triple/compound meters (3/8, 6/8 Teitsch/Waltz), often features “fiddling” passages and horns/bassoons. Haydn uses characteristic doubling of a violin melody by an oboe or bassoon. Haydn, Symphony No. 82 in C “The Bear,” finale.

Sacred: polyphonic, complex harmony, usually slower tempos, and alle breve meter (so-called “cut” time) but not always. Moderation of metric feel often necessary here. Coda of the finale of Mozart, Symphony No. 41 in C “Jupiter” (10:42-end).

Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress): minor mode, unison passages, often descending melodies, fast tempo, syncopation in accompaniment against straight beats in melody, unexpected accents, harsh dissonances, sometimes polyphonic passages. Haydn, Symphony No. 45 in F-sharp minor “Farewell,” mvt. 1 (0:05-5:02).

The topical states described above rely in part on mimesis, the artistic imitation of natural or familiar objects, places, emotional expressions, and conditions. Mimesis is a complex matter, with varying degrees of exposure to the arts from the naïve to the expert considered in its effectiveness. Despite its complexity, a helpful starting point for considering mimesis in instrumental music emerges by defining three types of mimetic treatment found in eighteenth-century music, from the most straightforward (most general, requiring the least knowledge of musical conventions) to the most conventionalized (requiring some knowledge of conventional dramatic meaning). These mimetic devices work together to generate musical meaning, and thus dramatic effects. Portions of the “Scene by the Brook” movement (ii) of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 in F “Pastoral” demonstrate these mimetic approaches.

Imitation of specific sounds. Natural sounds such as birds and other animals, thunder, raindrops, or manmade sounds of battle or gunshots, or even musical gestures used for specific purposes such as bugle or hunting horn calls, bagpipe drones, and shepherd pipe signals, are imitated in a direct manner that is easily recognizable by listeners. In setting the outdoor scene of the second movement of his “Pastoral” Symphony, Beethoven has the woodwinds imitate the sounds of actual birds, even going so far as to identify the birds by name in the score: nightingale (flutes), quail (oboe), and cuckoo (clarinet). Excerpt (11:28-12:11).

Imitation of motion. Melodic direction and motivic ideas imitate movement, such as the rising (ascending melody) or setting (descending melody) of the sun, the moment of someone falling into death (descending chromatic melody), or, as in the beginning of the Beethoven “Pastoral” Symphony movement, constantly moving descending motives in the second violins, violas, and cellos imitate the slow, easy, trickling motion of the brook. Excerpt (0:00-0:58).

Imitation of an emotional state, place, or idea. The imitation of sounds and motion described above are elements that aid Beethoven in creating the dramatic state of his “Scene by the Brook” second movement. But the totality of musical characteristics in this movement essentially imitate the state of repose in nature that Beethoven would like us to experience in this scene. The slow tempo with its rocking 12/8 compound meter (pervasive rhythmic triplet feel), compact, descending melodic motives that do not extend to the outer limits of an instrument’s range, moments of silence, generally soft dynamics, orchestration limited to the strings and woodwinds with an abundance of woodwinds solos and soft trills in the violins as birds singing in the canopy above, all serve to give a general sense of relaxation, and being in a natural (not indoor) setting. These elements coupled with the bird-call and brook-motion imitation come together to transport the listener to a reposed afternoon or evening in the woods or a meadow, along a beautiful flowing stream, up to the end of the movement. Excerpt (10:50-end).

3. A symphony’s dramatic content, especially a chamber symphony’s, fits into specific expectations of musical structure.

“The chamber symphony, which constitutes a whole in and for itself and has no following music in view, reaches its goal only through a full sounding, brilliant, and fiery style. . . . Such an allegro is to the symphony what a Pindaric ode is to poetry. Like the ode, it lifts and stirs the soul of the listener and requires. the same spirit, the same elevated powers of imagination, and the same aesthetics in order to be happy therein. . . . The andante or largo between the first and last allegro has indeed not nearly so fixed a character, but is often of pleasant, pathetic, or sad expression.”

The self-standing chamber symphony had emerged as the most significant orchestral genre by the end of the eighteenth century. Schulz’s description of the chamber symphony is his most thorough of the three types (theater, church, chamber), and shows that there were structural expectations for a chamber symphony, which worked together with specific topoi in generating drama. Schulz identifies the chamber symphony as having three individual movements—the outer movements expressing one set of dramatic topics that are characterized as grand or brilliant, and the inner movement, while not being “fixed,” contrasts the outer movements by expressing other, more intimate or “pathetic” topics, much like different acts or scenes of a single play. This three-movement structure describes the Italian model of the symphony which had developed out of the three-part form of the Italian opera overture, or sinfonia, and continued to be preferred by some Italian composers, as well as those in Salzburg, London, and some in Paris and Vienna. One movement type that Schulz does not discuss, but became common, is based on the aristocratic minuet dance, suggesting a galant or courtly topic. (I call this the “powdered-wig” movement when teaching it to younger musicians.) Beginning in the 1740s other composers, notably those at the Mannheim court, and some in Vienna and central Europe, inserted minuet movements between the slow and finale fast movements, resulting in a four-movement structure.

The multi-movement framework that symphonies and other Classical instrumental pieces followed is referred to as the Sonata Cycle. As Schulz describes, and the repertoire exemplifies, each movement of the cycle had its own dramatic-topical characteristics, and its own musical form, displaying some common thematic materials and tonal or key relationships. Before summarizing the four-movement Sonata Cycle, some helpful theoretical definitions are in order.

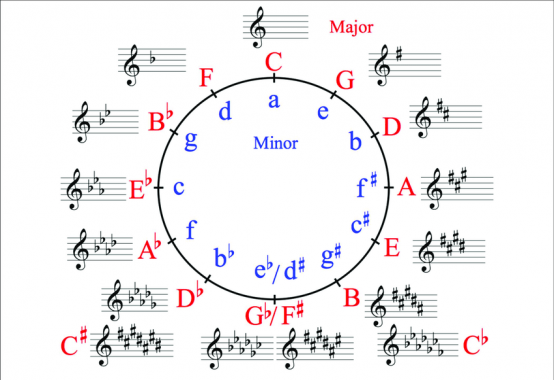

Tonal/Key relationships. A key or tonality is a set of seven (or ten) distinct pitches used any given time, identified by a keynote (strongest pitch) and a mode (major and minor). Below is a chart called the Circle of Keys (or Circle of Fifths) that can be used to explore key relationships.

During the late eighteenth century, certain closely-related keys were used within and among the movements. These keys were usually next to each other on the Circle of Keys, or reflect a mode change. For example, a piece said to be in the key of C major would begin and end in that key (called the “tonic” key), but would also contain material in G major (one position clockwise, called “dominant”) and F major (one position counter-clockwise, called “sub-dominant”)—those keys with keynotes a fourth or fifth apart—and possibly in C minor (change of mode to “parallel minor,” three positions counter-clockwise). A piece in C minor might also explore the major key represented by the same sets of pitches—E-flat major (same place on the wheel, called “relative major”). Beethoven’s symphonies follow these inherited common tonal relationships, he explored other relationships in his later symphonies, particularly those whose keynotes are separated by a third, e.g. C major and E-flat major or A major, called “mediant” (“sub-mediant”) key relationships.

Movement forms. Several common movement forms also emerge in the eighteenth century. The most complex and yet most common is the so-called Sonata-allegro form, which is almost always the form of first movements, and is based on contrasting themes highlighting different keys, which are explored through developmental procedures, and finally are resolved. A useful map of Sonata-allegro form can be found here.

Other common movement forms:

Theme and Variation. A simple usually two-part melody is introduced, then repeated several times, each time with a little difference in material called a variation.

Map: Theme—Var. 1—Var. 2—Var. 3 . . .

Minuet and Trio form. A type of ternary form. Dance music often came in pairs, with the first dance returning (called da Capo or “to the top”) after the second dance. The individual dances would usually have very predictable phrase structures in themselves, referred to as rounded binary or strict/simple binary, which were two-part forms that contained internal repeats (||: :|| signals to repeat the material in between).

Map: Minuet ||: a :||: b a’ :|| (rounded binary) or ||: a :||: b :|| (simple binary), then

Trio ||: c :||: d c’ :|| or ||: c :||: d :||, then

Minuet “da Capo” ||: a :||: b a’ :|| or ||: a :||: b :|| (with or without repeats)

Rondo. A “rondo” theme, usually simple or rounded binary in its structure, is introduced, and returns several times following new material called “episodes.”

Map: A (rondo theme)—B (episode)—A—C (another episode)—A = “five-part rondo,” or

A—B—A—C—A—B—A = “seven-part rondo.”

The four-movement Sonata Cycle. The typical cycle of movements partially described by Schulz, and that Beethoven inherited, looked something like this:

[Note: Studying Mozart’s Serenade in G, K. 525 “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” offers a helpful, clear model for understanding the four-movement Sonata Cycle.]

First Movement—

Tempo: Fast (allegro), possibly with a slow (adagio) introduction.

Key: tonic key (key identified in the title)

Form: Sonata-allegro form, with the second theme area being in the dominant (in a major-mode work) or relative major (in a minor-mode work).

Topics and Character: Full orchestra, noble, brilliant, C-major, other grand topics, sometimes contrasted by more lyrical and perhaps pastoral second themes; might start with a slow introduction of a majestic topic.

Second (Slow) Movement—

Tempo: Moderate (andante) or slow (largo, larghetto, adagio)

Key: Not the tonic; usually dominant, sub-dominant, or relative or parallel major or minor.

Form: Lots of variety. Might be a sonata form of some kind, or a Theme and Variation (favorite of Haydn in his late symphonies), or maybe Ternary.

Topics and Character: Contrasts grandeur of first movement. Subdued, usually reduced orchestra and softer dynamics at beginning. Relaxed, reposed or melancholy, sad, love, pastoral topics.

Third (Dance) Movement—

Tempo: Moderate, based on triple-meter galant (“powered-wig”) Minuet.

Key: tonic key

Form: Minuet-and-Trio ternary form, with rounded- and simple/strict binary internal structures.

Topics and Character: Noble, galant, aristocratic minuet(s), possibly contrasted by a more rustic, simple trio based on the Ländler Austrian folk dance. Full orchestra for the minuets, reduced orchestra, often highlighting wind instruments, for the trios. [The third movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 96 offers a clear example of this Minuet-Ländler juxtaposition.] Haydn’s later works, particularly his string quartets and symphonies, began playing with the high expectations this movement contained, particularly regarding its moderate tempo, clear triple meter, and predictable phrase lengths (based on four-bar segments). The result was a Scherzo (“joke”), which was too fast (tempo), had misplaced accents to throw off the triple meter, and added bars in the phrases to remove the predictability of the phrase lengths. The joke, then, was the thwarting of the listeners’ expectations based on the predictability of the movement. Nearly all of Beethoven’s symphonic third movements are scherzos, whether called that or not.

Fourth (Finale) Movement—

Tempo: Usually the fastest of all of the movements.

Key: tonic key

Form: Sonata-allegro or Rondo.

Topics and Character: While Schulz describes them along the same lines as the first movement, finales tended to be the most light-hearted and comic, even rustic, movement in the cycle—a “happy ending.” Folk and rustic topics prevail, although some composers do re-establish a noble or “learned” character, such as the finale of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 “Jupiter.” Beethoven came to treat the finale as a “heroic, victorious” dramatic goal which finally overcame the struggles of the rest of the symphony (the “astra” of per ardua ad astra), rather than a light-hearted, more comically-related happy ending.

As has been hinted at in the above descriptions, Beethoven will move the dramatic impact he detected as inherent in the Sonata Cycle to new directions and profundity by taking a teleological or end-aimed, goal-driven approach to the cycle, particularly through adding compositional weight to the last two movements.

—Contributor: MER

Beethoven’s Orchestra

Instrumentation and growth ca. 1740-1800

Schulz’s description of the instruments that “belong to” a symphony reflects the mid-century development of the orchestral ensemble, which continued to grow in size and tonal variety up to the time Beethoven completed his First Symphony in 1800, and throughout his own symphonies. The changes to and growth of orchestral instrumentation in the latter half of the eighteenth century occurred because of the recognition of instrumental music’s dramatic agency in music for the stage, and its possibilities of providing the same theatrical effects for audiences on its own, particularly through the referencing of musical topoi (see part 2 of the above essay).

Mid-century. As stated above, the foundation of the orchestra mid-century was a four-part string texture with multiple players on each string part, which would often be combined with four or seven additional instrumental parts, giving the “Orchestra of 8” and “Orchestra of 11” :

| Four-part Strings | Four-part Winds “of 8” | Additional parts “of 11” |

| Violin 1 | Oboe 1 (Flute 1?) | Trumpet 1 |

| Violin 2 | Oboe 2 (Flute 2?) | Trumpet 2 |

| Viola | Horn 1 | Timpani (tonic & dominant) |

| Basso* | Horn 2 | |

| *Cellos, Double basses, 1 Bassoon, Harpsichord(?) |

1760s-70s. During the 1760s and into the mid 1770s, the winds in opera orchestras and several court orchestras, including those in Vienna, Salzburg, Mannheim, and the Esterházy court in Eisenstadt, Haydn’s employer, began to expand. This was due in part to the “reform operas” of Christoph Willibald von Gluck, but also to an emerging cosmopolitanism that valued wind players from Central Europe, and an inclusion of court music of the Harmonie—wind ensemble—the core of which included two oboes, two horns, and two bassoons, but could have other wind instruments such as flutes and clarinets added or replacing the oboes. The symphonies of the Mannheim composers were especially influential on others for their instrumental colors and orchestral effects. The first significant regular shift in this direction was the addition of one or two flutes above the oboes, followed quickly by the transfer of the bassoon from the basso part to its own part and the addition of another bassoon part. This became a regular configuration for symphonic works by the late 1770s. The Harmonie was commonly associated with topics related to the outdoors, such as pastoral scenes, rural people and places, the hunt, etc. As before, the addition of two trumpet and timpani parts would signal the celebratory “C-major” fanfare style, royal and battle topics. Thus, by the end of the 1770s, there is a real sense of two different instrumental ensembles—strings and winds—at times working together and at times functioning separately, allowing for a great variety of tonal color and dramatic/topical possibilities. The increase in the winds also reduced the need for harpsichord to play with the basso and fill in harmonies. By 1780, a typical symphony would have the following instrumentation, which would be adjusted for specific desired dramatic purposes:

| Four-part Strings | Winds | Additional parts (C-major style) |

| Violin 1 | Flutes 1 (& 2?) | Trumpets 1 & 2 |

| Violin 2 | Oboes 1 & 2 | Timpani (tonic & dominant) |

| Viola | Bassoons 1 & 2 | |

| Basso* | Horns 1 & 2 | |

| *Cellos & Double basses |

Some operas would also include other instruments such as harpsichord and harps for accompanying voices, and trombones for representing sacred, supernatural, or ghostly (ombra) scenes, but trombones in symphonies would have to wait until Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

1780s-90s. By the last two decades of the eighteenth century, symphony composers were regularly using the above instrumentation, but experimenting with other mixtures. Mannheim and Parisian composers, as well as Mozart, made more common use of the clarinet, either replacing oboes or added to them. After Mozart moved to Vienna in 1781, his operas, piano concertos, and symphonies all show increased and interesting uses of the clarinet, reflecting a mastery of the instrument he gained in writing several wind serenades during his last years in Salzburg (late 1770s). He wrote two version of his G minor Symphony No. 40 in 1788—the first without clarinets and the second including clarinets, which required some changes to the oboe parts. Haydn came to the clarinet later, with five of his last six “London” Symphonies (Nos. 99-104, composed 1794-95) including clarinets, especially for folk or rustic topics, as in the trio of the third movement of his Symphony No. 103, where clarinets and a bassoon double the string melodies, enhancing the folk quality of this Ländler. Trumpets and timpani also came to be used more regularly, in a variety of keys. When Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, and began his symphonic oeuvre, he inherited the following quite colorful “standard” symphony instrumentation:

| Four- or Five-part Strings | Winds/Brass/Percussion |

| Violin 1 | Flutes 1 & 2 |

| Violin 2 | Oboes 1 & 2 |

| Viola | Clarinets 1 & 2 |

| Cello* | Bassoons 1 & 2 |

| Double bass* | Horns 1 & 2 |

| *together or separated | Trumpets 1 & 2 |

| Timpani (tonic & dominant) |

Beethoven would continue to expand the orchestra in his symphonies by adding parts for piccolo (Syms. 5, 6, 9), contrabassoon (Syms. 5, 9), and trombones (three in Syms. 5 & 9, two in Sym. 6). Others before him had occasionally included four horns instead of just two, as well as the “Janissary” percussion instruments of bass drum, cymbals, triangle, but these were rare. Beethoven would have three horns playing in his “Eroica” Symphony No. 3, and the Janissary percussion in Symphony No. 9. He would also regularly separate the cello parts from the double basses, giving a five-part string texture. In all of these cases, Beethoven was careful to use these instrumental sounds to bring to life the dramatic topics with which they were associated, and not just for the purpose of increasing the sound. In other words, Beethoven’s dramatic outlook in his symphonies led him to a consideration of orchestral sound that would clarify and make more immediate for the listener an emotional journey unique to each symphony.

The Instruments

The instruments of Beethoven’s day were constructed somewhat differently than those of today’s orchestras, and thus had different sounds and strengths or modes of playing that reflected their construction and character. Below are some brief descriptions of the orchestral instruments for which Beethoven composed, and some demonstrative videos that provide details of each instrument’s construction and sound.

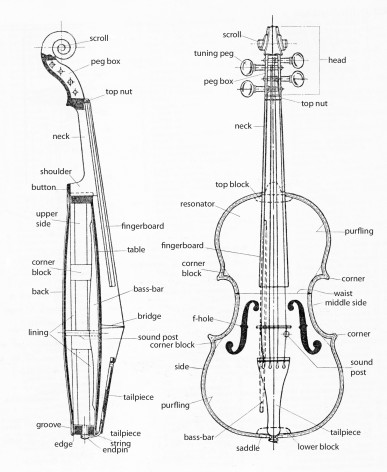

String instruments. (See construction images.) In general, string instruments of Beethoven’s time had shorter fingerboards, which were at a much flatter angle from the body, and shorter bridges, so the strings were closer to the body of the instruments.

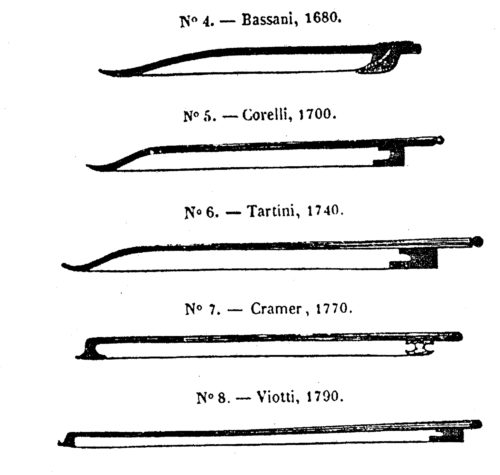

Cellos did not yet have endpins, at least not as a regular feature, so they were held on the calves of the players. Strings were made of sheep intestines—“gut” strings—rather than metal as today. The resulting sound was less bright and softer than today’s strings. Modern players will sometimes say that the period set-up allowed for subtlety and a delicacy of expression that modern instruments do not. Bows, too, were constructed differently; the wood was more parallel with the hair than in modern bows, although by 1800 they more closely resembled modern bows than they had even twenty years before. See the “Viotti Bow” in the diagram below.

Videos about the string instruments

The Bow: Henrietta Wayne, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (OAE)

Violin and Viola: Lisa Grodin

Cello: Luise Buchberger, OAE

Double bass: John Feeney, American Classical Orchestra

Woodwinds. Generally speaking, woodwinds might sound more “rustic” to modern ears than their current counterparts, particularly oboes and bassoons. This made them ideal for use in pastoral and rustic topoi. Flutes were made of wood, not metal, thus giving them a softer sound. Clarinets generally had a less warm sound than the modern instrument, and the tone qualities of the low, medium, and high registers were noticeably different: the low “barked,” the middle was warm, and the high brilliant. All of the woodwind instruments had fewer keys, and thus different fingering systems were developed to alleviate some intonation difficulties.

Videos about the woodwinds

Flute and Piccolo: Lisa Benznosiuk, OAE. ORR Symphony No. 5, piccolo

Oboe: Dan Bates, OAE. ORR Symphony No. 5 Oboe solo on period oboe.

Clarinet: Emily Worthington, Boxwood & Brass. Symphony No. 8, mvt. 3 trio: clarinet and horn solos

Bassoon and Contrabassoon: Peter de Koningh, Boxwood & Brass. David Chatterton, OAE

Brass and Timpani. The most prominent difference in the brass instruments compared to today is that they were “natural” instruments, devoid of valves that allowed them to play chromatically (all of the pitches). Thus, they could only play specific pitches in the lower register, but more melodically as they got higher. This resulted in stylistic playing gestures such as “horn fifths” and fanfare figures that related to topics such as the hunt and the rustic for horns, and battle, military, and royal associations for trumpets. Horns were called upon to play in most keys, using a system of interchangeable tubing lengths called “crooks.” Trumpets were most commonly built to lengths for playing in C major and D major, but trumpets in B-flat and E-flat were also used. Throughout the eighteenth century, horn players developed a sophisticated technique of “horn stopping” which allowed for chromatic playing even in the lower registers, although with some changes in tone quality. Trumpets were generally less bright in tone quality than their modern versions, and could play with both power and delicacy. Timpani almost always played with trumpets, but they were beginning to gain some independence. They were usually tuned to the tonic and dominant pitches of the piece, e.g. D-A, C-G, B-flat—F, and did not have quick tuning mechanisms such as the pedals of today’s instruments. Timpani sticks were harder than today’s, usually wood and sometimes wrapped with leather. Trombones had smaller bells, and usually played together in an ensemble of alto, tenor, and bass, each of a different length and tone color. Trombones (sackbuts) had long been used for doubling choral voice parts in sacred music, thus giving them topical associations with the sacred, supernatural, and ghastly.

Videos about brass and timpani

Horns: This video by Richard Seraphinoff describes many of the aspects of horn construction and playing techniques. Anneke Scott, Boxwood & Brass. Symphony No. 8, mvt. 3 trio: clarinet and horn solos on period instruments

Trumpets: EBS & ORR video: evolution of orchestral trumpets from Bach to Berlioz.

Trombones: ORR Symphony No. 5, mvt. 4 excerpt, including period trombones, trumpets, other winds.

Timpani: Mark Goodenberger, Portland Baroque Orchestra

Others (bass drum, cymbals, triangle)

Practice of re-orchestration

During the early years of the nineteenth century the instruments described above were undergoing changes in construction at a fairly quick pace, more and more resembling those we hear in today’s orchestras. String instruments were getting longer and brighter, new systems of keys were being developed for woodwind instruments, largely influenced by Theobold Boehm’s flute system, and valves were added to horns and trumpets, allowing for fully chromatic playing; Heinrich Stölzel was among the first to do this. Such changes in the capabilities of the instruments, as well as in their tone qualities which effected the balance of sounds in the orchestra, spawned a practice of conductors re-orchestrating Beethoven’s works. This was not a new practice; even in the eighteenth century, as older music was being brought into the contemporary repertoire, “modernizing” was considered essential for offering the best performances for the public. Perhaps the most well-known eighteenth-century case of modernizing a piece was Mozart’s re-orchestration of Handel’s Messiah, a project the diplomat and music connoisseur Baron Gottfried van Swieten urged Mozart to undertake in 1789, as van Swieten was introducing Handel’s music to Vienna. The most noteworthy Beethoven re-orchestrations were by Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, and Felix Weingartner. Wagner and Weingartner published essays on their reorchestrations, and some of these rewritings are still in use today. (See Felix Weingartner, On the Performance of Beethoven’s Symphonies.)

Orchestra size for first and early performances

The numbers of instruments in orchestras of the day widely varied. Most orchestras in Vienna concerts would have had about 35-40 players, with the distribution being approximately 12-16 violins, 3-4 violas, 3-4 cellos, 4-5 basses, and one-per-part in the winds. In private concerts these numbers would have been on the lower end, even slightly less. After about 1810 some special concerts, called Akademies, would be able to secure larger forces by combining professional and amateur performers. These larger groups might be the size of a modern symphony orchestra, having as many as 40 violins, 12 violas, 10 cellos, and 8 double basses, at times doubled by one or two contrabassoons. When string forces included more than about 25 violins and comparable violas, cellos, and basses, wind parts would be doubled (two-per-part) for the tutti—full orchestra—passages. Below is a list of the first performances of Beethoven’s symphonies with estimates of the ensemble sizes for each based on existing evidence, and information on series of Beethoven symphony performances by the Gesellshaft der Musikfreunde and Concerts Spirituel during Beethoven’s lifetime.

String numbers: Violin1+2.Viola.Cello.Bass

Winds: Single=one player per part, Double=two players per part on tutti sections.

Symphony No. 1 in C, Op. 21

First Performance: 2 April 1800, Akademie in Burgtheater, probably the Italian Opera Orchestra

Estimated orchestra size: 8+8.4.4.5 / Single winds

Remarks: Reviewer in Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (hereafter AMZ) of 1800 said this orchestra had five basses. Other numbers estimated from that statement based on common orchestra sizes.

Symphony No. 2 in D, Op. 36

First Performance: 4 or 5 April 1803, Akademie at Theater-an-der-Wien.

Estimated orchestra size: 6+6.3.2.4 / Single winds

Remarks: Approximate size of orchestra according to Adam Carse, The Orchestra from Beethoven to Berlioz(New York: Broude Bros., 1949). Symphony No. 1 also performed.

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat, Op. 55 “Eroica”

First Performances: 9 June 1804, Lobkowitz Palace, Vienna (private); 7 April 1805, Theater-an-der-Wien (public)

Estimated orchestra size: 3+3.2.2.2 / single winds (private; “at least . . .”); 6+6.3.2.4 / single winds (public, estimate)

Remarks: Numbers given for the first private performance at the Lobkowitz Palace are based on a letter by Beethoven requesting “at least” these forces. Numbers for first public concert based on the Carse source cited above.

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, Op. 60

First performance: March 1807, Lobkowitz Palace, Vienna.

Estimated orchestra size: 6+6.3.4.2 / single winds

Remarks: Numbers based on a description of an earlier “run through” of symphonies at the Lobkowitz Palace.

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, and Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 “Pastoral”

First performance: 22 December 1808, Akademie at Theater-an-der-Wien.

Estimated orchestra size: 12-16.3-4.3-4.3-5 / single winds

Remarks: Both symphonies premiered in same concert, with Beethoven leading the orchestra.

Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92

First performance: 8 Dec. 1813, Akademie at University Concert Hall, Vienna.

Estimated orchestra size: at least 13+12.7.6.4 / possibly double winds

Remarks: These numbers based on a report of a Clement academy concerts from 1807-08, when academies had moved the larger University Concert Hall; Beethoven’s first four symphonies were performed on these concerts. The orchestra for the 1813 Symphony No. 7 concert was likely larger. See Otto Biba, “Concert Life in Vienna,” in Beethoven, Performers and Critics: International Beethoven Congress, Detroit, 1977 (Detroit: Wayne State Press, 1980).

Symphony No. 8 in F, Op. 93

First performance: 27 February 1814, Akademie at palace Redoutensaal, Vienna.

Estimated orchestra size: 18+18.14.12.7(+2CBsns) / double winds

Remarks: Concert included Symphony No. 7 and Wellington’s Victory. String numbers were reported by Beethoven himself in a letter, and such a large string contingent would have probably called for doubling the wind parts at tutti (full orchestra) sections, as was the practice of the day. In Beethoven’s list of string numbers, he included the comment “and two contrabassoons” following the bass number, indicating that, as was sometimes the practice, contrabassoons could double the bass parts in larger orchestras.

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral”

First performance: 7 May 1824, Kärtnerthor Theater, Vienna.

Orchestra size: 12+12.10.12.12 / double winds / 80-100 in chorus.

Remarks: According to Thayer (Life of Beethoven, ed. Forbes, 905), Schindler wrote a letter to Louis Duport on 24 April 1824 regarding size of the ensemble for the upcoming concert, listing the numbers given here. It was a mixture of amateurs and professionals, and only two rehearsals were possible before the performance.

The Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde performed all of Beethoven’s symphonies except Nos. 1, 6, and 9 between 1816 and 1821. According to Biba (“Concert Life in Vienna”), the size of this large orchestra at this time was 20+20.12.10.8 / double winds

The Paris Concerts Spirituel, in its two seasons 1819-20 and 1820-21, performed all of the eight completed symphonies. Based on a copperplate image of seating from 1825, Clive Brown (“The Orchestra in Beethoven’s Vienna”) estimates the orchestra’s size at this time was 10+10.10.6.4 / single winds.

Direction and instrument “seating” arrangement

The modern baton conductor was not yet a fixture in orchestras for instrumental music. Orchestras were led by either the concertmaster (first violinist), or less often a keyboardist. In the case of vocal music, a “dual direction” was often practiced, where the concertmaster would lead the instruments and the keyboardist (organ, harpsichord, or fortepiano) the voices. However, reports of performances of Beethoven’s symphonies describe situations where Beethoven would be leading the ensemble using elaborate gesticulations, or would be on stage next to the leader providing tempos. The story of the first performance of the Ninth Symphony includes Beethoven’s role in setting tempos, but also relates the tender moment that occurred at the end, when the alto soloist Caroline Unger had to turn Beethoven towards the audience so he could observe its enthusiastic applause, which he could not hear.

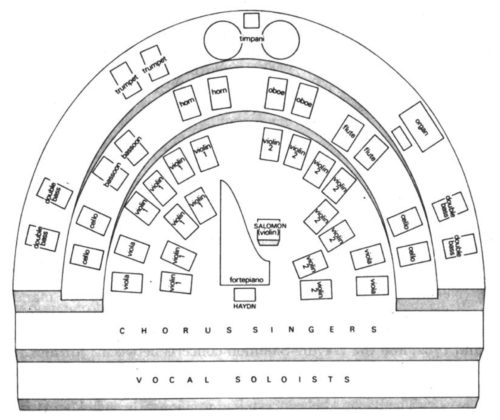

While we use the term “seating” to describe the arrangement of instruments in the performance space, this is misleading. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries musicians generally stood for performances, except for cellists and keyboardists. There are several images and descriptions of instrument configurations from the years surrounding 1800, from opera houses, festivals, chamber and other instrumental performances. While these indicate a variety of possibilities, a few consistencies do present themselves:

- Violins are to the front of the space, with violin 1 and violin 2 on opposite sides (violin one usually to the left of the “leader,” or stage right, and violin 2 on the other side, stage left).

- At least one cello and double bass would be near the keyboard (if present), near the middle of the setup, thus aiding in the basso stating together. Sections of cellos and double basses would be near the back and distributed on both side of the performance area (stage right and left), often behind the violins.

- Violas go wherever they could fit, and as with cellos and basses, usually distributed on both sides of the setup.

- Woodwinds and horns stood together, usually in a line.

- Trumpets, timpani, and trombones if used, stood to the back.

- In the case of choral concerts, singers would usually be in front of the instruments, towards the audience.

Nearly all of these trends can be seen in this hypothetical reconstruction of the seating arrangement for the London Salomon concerts of 1791-92, when Joseph Haydn was present and his Symphonies Nos. 93-98 were performed, generated by Neal Zaslaw based on contemporary descriptions and sources (“Towards the Revival of the Classical Orchestra”).

—Contributor: MER

Topics and readings for further inquiry

Schulz’s “Symphonie” description

Churgin, Bathia. “The Symphony as Described by J. A. P. Schulz (1774): A Commentary and Translation.” Current Musicology 29 (Spring 1980): 7-16. Columbia Academic Commons link.

The eighteenth-century symphony before Beethoven

Brown, A Peter, gen. ed. The Symphonic Repertoire, Vol. I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony. Edited by Mary Sue Morrow and Bathia Churgin. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Libin, Laurence Elliot. “Symphony.” Britannica.com. Accessed 10/10/2020.

Classical music topics (topoi) and mimesis; the Characteristic Symphony

Agawu, V. Kofi. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classical Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Caplin, William E. “On the Relation of Musical Topoi to Formal Function.” Eighteenth-Century Music 2/1 (Spring 2005): 113-24.

Hatten, Robert S. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Huovinen, Erkki. “The Semantics of Musical Topoi: An Empirical Approach.” Music Perception 33/2 (Dec. 2015): 217-43.

Lowe, Melanie. Pleasure and Meaning in the Classical Symphony. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Monelle, Raymond. The Musical Topic: Hunt, Military and Pastoral. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Ratner, Leonard. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. New York: Schirmer, 1980.

Sisman, Elaine. “‘The Spirit of Mozart from Haydn’s Hands’: Beethoven’s Musical Inheritance.” In The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven, edited by Glenn Stanley, 43–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Cambridge Core link. [This is an excellent, concise, and clear assessment of topics and formal principles of the style Beethoven inherited.]

Tolley, Thomas. Painting the Cannon’s Roar: Music, the Visual Arts and the Rise of an Attentive Public in the Age of Haydn, c.1750 to c.1810. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2001.

Will, Richard. The Characteristic Symphony in the Age of Haydn and Beethoven. New York: Cambridge, 2002.

Structure and form in the symphonies

Caplin, William E. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Development of the orchestra in the eighteenth century; orchestras in Beethoven’s Vienna

Biba, Otto. “Concert Life in Vienna.” Beethoven, Performers and Critics: International Beethoven Congress, Detroit, 1977. Detroit: Wayne State Press, 1980.

Brown, Clive. “The Orchestra in Beethoven’s Vienna. Early Music 16 (1988): 4-14, 16-20. JStor link.

Koury, Daniel J. Orchestral Performance Practices in the Nineteenth Century. Ann Arbor, MI: U.M.I. Research Press, 1986.

Spitzer, John, and Neal Zaslaw. The Birth of the Orchestra: History of an Institution, 1650-1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Zaslaw, Neal. “Toward the Revival of the Classical Orchestra.” Proceedings of the Royal Music Association 103 (1976-77): 158-87. JStor link.

Beethoven’s orchestration technique and logic

Botstein, Leon. “Sound and structure in Beethoven’s orchestral music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven, edited by Glenn Stanley, 165-85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Cambridge University Press link.

Reorchestration of Beethoven’s symphonies

Folliard, Peter. “On the Incorporation of Weingartner’s to Beethoven’s Symphonies.” Unpublished paper, Eastman School of Music, 2016. An expanded version of this study will soon be published in the Conductor’s Guild Journal.

McCaldin, Denis. “Mahler and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.” Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association107 (1990-91): 101-10. JStor link.

Weingartner, Felix. On the Performance of Beethoven’s Symphonies. Translated Jessie Crosland. New York: Kalmus, 1906.