Morgan Patrick

Abstract

In certain Hollywood films of the past half century, a i – IV progression class accompanies protagonists and filmgoers alike as they cross the threshold into wondrous realms. I trace this scoring practice to a homology between narrative passage into fantasy and structural aspects of the progression, in which encounters with otherworldly elements can be read into its tonal markedness, voice leading properties, and functional indeterminacy. A series of examples demonstrates how composers leverage the second triad’s relationship to its preceding tonic to embody outward expansion, intermix familiar and foreign elements, and charge a functional tension between arrival and departure, all qualities that are central to the ethos of fantasy encounters. Together, these features enable a distinction between the i – IV progression’s fantasy use and the use of similar progression classes or normative major subdominant contexts, thereby inviting its categorization as a distinct progression class I call the “Fantasy Fifth.”

View PDF

Return to Volume 36

Keywords and Phrases: film music; homology; conceptual metaphor; tonal function; triadic progression

of this vignette.

Introduction

Much has been written on the expressive use of triadic chromaticism to convey elements of the other-worldly. Ranging from the uncanny (Cohn 2012), to the benevolently mysterious (Bribitzer-Stull 2015), the wondrous (Lehman 2018), and the heroic and sinister (Heine 2018), dramatic narrative associations latch themselves with seeming ease onto the tonally marked motions of unexpected triadic progressions. Scott Murphy’s (2014a) lexicon of tonal-triadic progression classes (“TTPCs”) offers a framework for inventorying associations between harmonic progressions and narrative use. In this study, I explore one such association in which the progression of a minor tonic to its major subdominant homologizes to a conduit between the worldly and the fantastic.

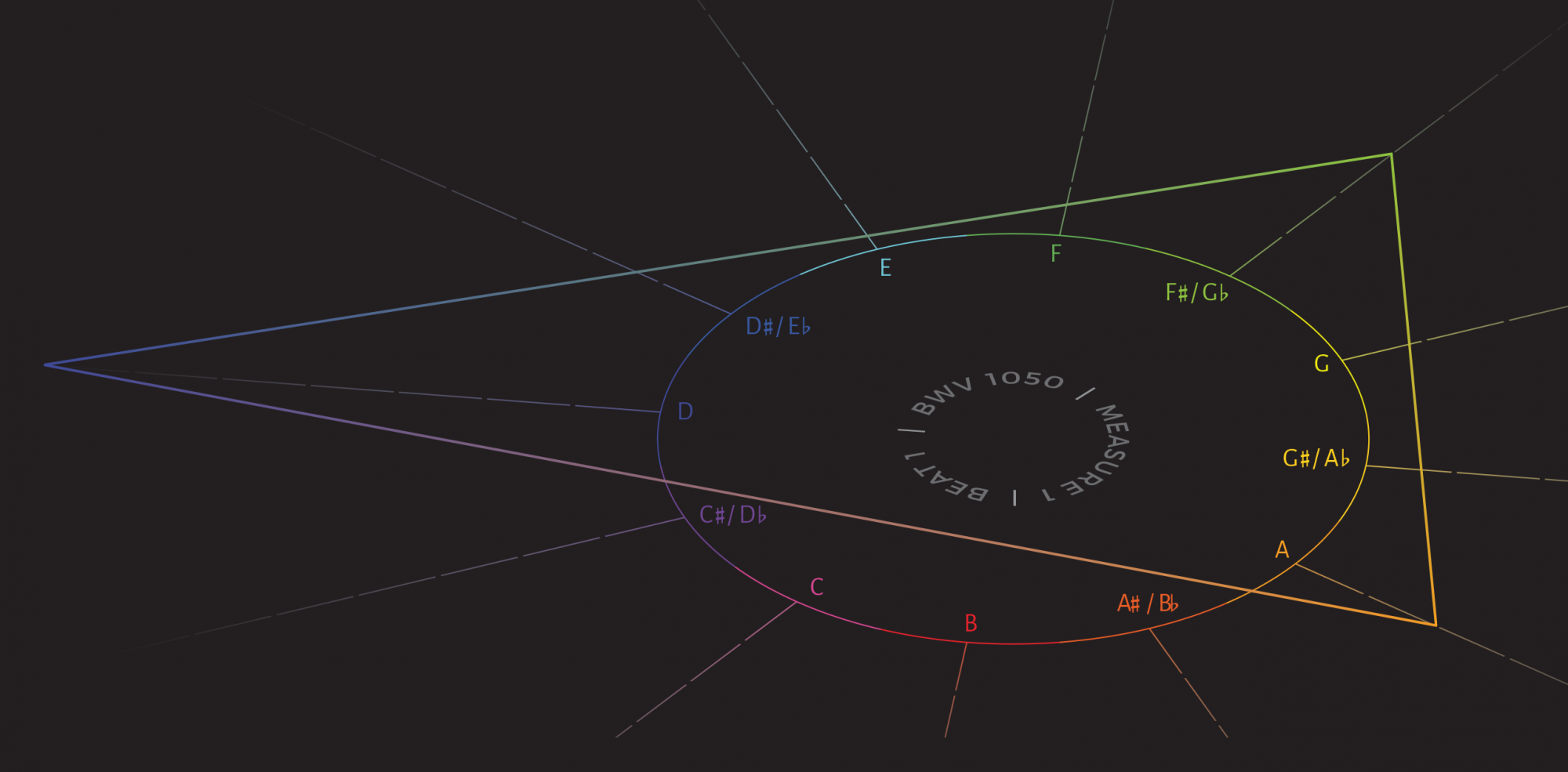

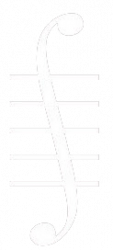

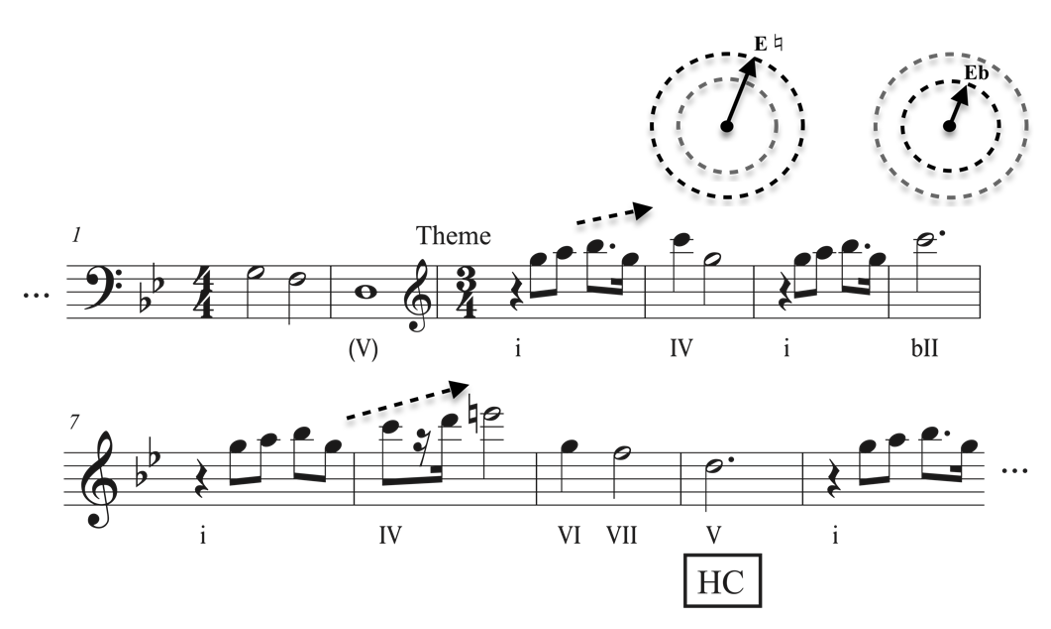

Figure 1 depicts the idealized voice leading of what I will call the “Fantasy Fifth” progression.1 In addition to foregrounding its recurrent thematic use in fantasy films, the name is intended to reflect a kinship to Frank Lehman’s more inclusive (and neo-Riemannian-inspired) Far Fifth involution (“F”), which is defined as a move between any two fifth-related triads of opposite modes where the common tone is the fifth of the major triad and the root of the minor triad (Lehman 2018, 90). Lehman partitions the F into two sub-classes that distinguish between orderings of the F-related triads: major-to-minor (“F(M)”) and minor-to-major (“F(m)”) variants. Both classes are tonally agnostic progressions, thereby advantageous for a range of cinematic contexts in which tonicity may be either inaudible or irrelevant. By contrast, the Fantasy Fifth’s expressive use rather hinges on a palpable tonal departure from a tonic minor triad – that is, it enforces tonicity in addition to the chord order. Thus, Fantasy Fifths are a subset of the F(m) class.

Since it is a tonic-specifying subset of F(m), the Fantasy Fifth can be more compactly represented using Murphy’s analytic innovations to the TTPC system, which enable analysts to flexibly specify which structural features – e.g., chord order, tonicity, transpositional invariance – are relevant for membership (Murphy 2020, 40–44; forthcoming). By this system, the Fantasy Fifth can be labeled “m5M∅:” a minor triad (“m”) progresses to a major triad (“M”) whose roots are five (“5”) semitones apart, and the progression class is neither order-neutral nor key-neutral (“∅”) – that is, it enforces the minor-to-major ordering as well as the first triad’s tonicity.2 While this label may initially seem cumbersome compared to “i – IV,” it has the distinct advantage of circumventing an overdetermined interpretation of the role of IV: we will see that the IV triad is a rather chameleon-like anti-tonic, sometimes admitting of multiple functional interpretations in productive tension with one another. Even for TTPCs amenable to Roman numerals, Murphian labeling can highlight other formal properties that are arguably quite accessible to lay filmgoers, such as coarser tonic-antitonic polarity and triad order. Nevertheless, in the analyses that follow I will retain Roman numerals to foreground the progression’s relationship to a larger tonal context.

1. Stylistic Precedent and the Basis for Homology

Interestingly, Lehman and Murphy have already observed that progression class supersets of the Fantasy Fifth suggest themes related to the fantasy genre. Lehman notes that the F transformation seems to connote “adventure” and “vast astonishment, particularly of oceanic origin” (2018, 61). Likewise, Murphy finds that a minor or major tonic progressing to its F-related triad associates with “wonderment, optimism, success, or transcendence” (2014, 48). Since these insights cut across triad orders and tonal orientations, they would seem to implicate the absolute relationship between the triads, rather than order or tonicity per se, in enabling these thematic these associations. Casting a topic-theoretic lens on this foundation, Dan Obluda seeks to distinguish narrative use based on triad order. He observes that F(m) readily aligns with extra-harmonic elements like orchestration and visuals to suggest topical associations like “the heroic,” while F(M) evokes “wonder” and both orders map to “transcendence” and “nature” (Obluda 2021, 223, 273, 290, 302). My reading of Obluda’s invocation of topic is that it productively challenges the notion that musical style elements must be taken out of their proper context for topical signification (Mirka 2014: 2, 20–23); indeed, the F transformation is quite at home in Lehman’s “Hollywood sound” (2018, 49), a fact that makes predicating association on historical precedent a worthy pursuit. For the present study, we can ask: are there any occurrences of the Fantasy Fifth in the repertoires of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to suggest an association with programmatic elements of the fantastic?

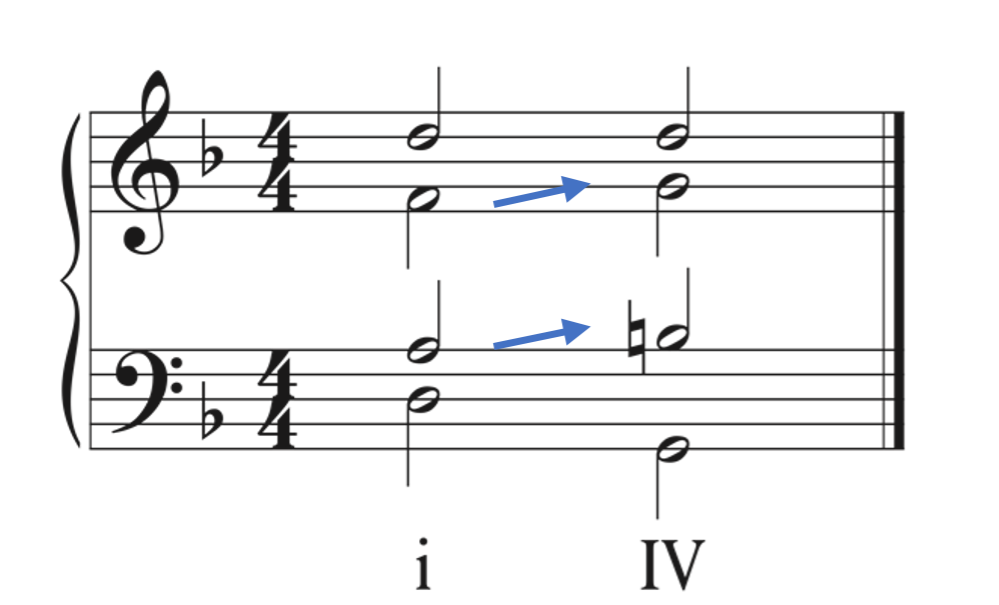

One possible precursor is found in Camille Saint-Saëns’ Le Carnaval des Animaux. Evoking a mystical underwater world, the “Aquarium” movement begins with a slow-paced sentence (Figure 2) whose presentation consists of a diatonically unremarkable i 🡪 iv$$^{6}_{4}$$ progression followed by the modally mixed i 🡪 IV$$^{6}_{4}$$. The parallel structure ensures that the IV is understood as a transformation of the preceding subdominant minor triad, coming as a veridical shock against the otherwise repeated basic idea. But this moment violates schematic, as well as veridical, expectations.3 4 Like many of the film instances reported below, this example resists a straightforwardly Dorian interpretation, according to which the IV would have been entirely unmarked. Rather, a larger tonal context normatively containing lowered sixth scale degrees – in this case, functional minor – ensures that IV is foregrounded. Moreover, because the IV’s quality matches that of a dominant triad, and because it “progresses” both from the minor subdominant of the previous idea and the interspersed augmented sixths, it admits of a distinctly “after-the-subdominant”-like quality despite its larger-scale tonic-prolongational function, a distinction inspired by Drew Nobile’s dissociation between progressive and syntactic definitions of tonal function (2016, 153).5 Saint-Saêns then brings back the i 🡪 IV in the continuation by modifying an ongoing D2 sequence, this time with IV serving as an unproblematic pre-dominant.6 Thus, the passage points up the IV triad’s amenability to multiple functional interpretations, a feature well-suited to evocations of things elusive or unknown, and one we will observe in the film examples below.

Aside from this singular programmatic use, I have found few other consistent pairings of the progression with programmatic elements of fantasy within the late nineteenth and early twentieth century repertoires (and would welcome readers’ suggestions as to others).7 The seven cinematic instances featured in this vignette (Appendix) point to the progression’s fantasy-themed use by Hollywood composers. Following Murphy’s logic that, absent a robust stylistic precedent, structural relationships between the triads of the i–IV may underlie the association (2014b, 306–310), I explore several distinct sources of evidence for homology between the structure of the Fantasy Fifth and encounters with fantasy elements in narrative. In doing so, I follow Richard Cohn (2004, 286) and subsequently Murphy, who define homology as an iconic resemblance between progression and extra-musical associations.

2. Embodying Upward Expansion: A Conceptual Mixture

Whereas a traditionally topic-theoretic approach seeks meaning in an iconic resemblance to a preexisting genre (Mirka 2018, 29), by contrast conceptual metaphor sources meaning directly to embodied knowledge of the world. According to this approach, image schemas act as generalized knowledge structures unifying and guiding our subsequent conceptualization of experience (Johnson 1987, xiv). Both embodied and preconceptual, image schemas appeal to the perceptual immediacy of film music and, more importantly, its coexistence with the multimodality of narrative and visuals (Chattah 2006, 28). Therefore, I turn to several image schemas whose mixture acts as an interface between the progression’s structure and motion into fantasy.

In Figure 1’s idealized voice leading, the fusion of two voices ascending by whole step is particularly prominent against an oblique common tone, a configuration that diverges from the normatively unequal ascending steps of a tonic passing to its subdominant.8 This upward voice leading can invoke the verticality image schema, in which pitch relationships are relationships in vertical space (Zbikowski 2002, 70), and is especially striking when the Fantasy Fifth accompanies visual ascents onscreen.9 Conceptual metaphor theory associates “up” with power, irrationality, and positive emotion (Cian 2017), three features that are central to conceptions of fantasy. The link to positive emotion is particularly relevant because the sharp-ward and minor-to-major traversals which map to ascent are likewise associated with brightness (Brower 2008, 26) and positive valence (Cook 2007). Moreover, as this progression moves from its tonal center, the verticality schema joins with the source-path-goal schema to suggest a departure from some metaphorical home (Brower 2000, 350). Of course, these invocations of ascent and departure hardly distinguish the Fantasy Fifth from other tonic-predominant progressions, but they do distinguish it from related F classes, such as the tonic-tending F(m) (v – I) and all the F(M) progressions, which descend against the common tone.

Thus, the progression is poised to evoke a positively-tinged departure, but why toward fantasy? Just as the otherworldly extends beyond the bounds of the normal, the raised sixth scale degree’s distance from tonic extends beyond that of its diatonic counterpart.10 Following Brower (2000, 345–346), we can invoke the combination of the center-periphery and container image schemas to represent tonic as the center of a metaphorical container from which other harmonies move outward. Introducing chromatic pitches enlarges the size of the container, thereby invoking a sense of expansion (Clark 2018, 112). Critically, unlike other TTPCs evoking otherness, this one’s second triad retains elements of the diatonic collection to ensure IV is not entirely foreign, a point taken up in the next section.11 In short, this image schema combination parallels the sense in which fantasy departs from and transcends ordinary limits.

Alan Silvestri’s title sequence for Night at the Museum provides a compelling demonstration of how surface realization can reinforce these properties of ascent, departure, and expansion. A series of preluding Fantasy Fifths gives way to the title image of an expanding ball of light emanating from within the museum, seemingly foreshadowing the museum exhibits’ breaking out of their containers and coming to life. This image fittingly aligns with the presentation of the theme (Figure 3 and Appendix – 1), whose expanding melodic intervals (mm.3–4), juxtaposition of raised and lowered $$\hat6$$ (mm.4 & 6), and ascending melodic line (mm.3–4, 7–8) reinforce the upward and expansional qualities discussed above. The continuation then presents another i – IV, whose melody ascends further up the IV triad to the raised sixth. Combined with upward-oriented camera angles of the accompanying shots, this scene beckons us to look up – and beyond the limits of the ordinary.

Though IV in functional minor is a rarer subdominant than iv, this does not mean that raised $$\hat6$$ is generically unusual in fantasy film music. In one of many Dorian-inflected films in which IV is not schematically unexpected, John Powell exploits a change of mode to render this chord salient. In How to Train Your Dragon, the repeated Fantasy Fifth cells that shuttle the viewer from main titles into the dragon-filled world of Berk come on the heels of a major-mode brass chorale containing subdominant harmony (Appendix – 2). The abrupt switch to the parallel minor at the Fantasy Fifths (0:00:25) means that the IV triad’s circle-of-fifths and voice-leading distances are now larger than they were to the preceding major tonic. In this case, it is the tonic’s change of mode, rather than the subdominant’s, that renders the Fantasy Fifth a comparatively wider traversal.

Importantly, this usage reflects a broader point that the Dorian mode is itself marked against those modal or tonal idioms with a lowered sixth. By calling forth a Dorian idiom, IV becomes the triad that clarifies the position of $$\hat6$$.12 In five of the other seven film examples surveyed, both versions of $$\hat6$$ freely intermix. Such Dorian-esque blending only serves to accentuate the comparatively further distance of the raised sixth, regardless of whether one views this intermixing as a generic default or modal mixture within either the functional minor or Dorian mode. Though not always unexpected, the IV triad is thus contextually marked.13

In combining image schemas to create a conceptual space in which this progression’s homology to fantasy may be distinguished from other F variants, I follow recent developments in cognitive linguistics proposing that such combinations generate emergent concepts that are more specific than those invoked by any one schema.14 However, this mixture by itself does not allow the Fantasy Fifth to lay sole claim to embodied evocations of outward expansion. Other chromatically inflected minor-to-major ascending departures from tonic, such as i–*fII (m1M∅) or a tonic-departing hexatonic pole (m4M∅), would be equally suited to the present metaphorical correspondences with fantasy induction. In his adaptation of Richard Cohn’s approach, Murphy cautions that the strength of a homology rests on its unique fit to a specific progression. We would thus be right to ask: is there an additional distinguishing feature at work here beyond this image schema mixture?

3. The Conduit Metaphor: Narrative Alignment and Scale Degree Hermeneutics

To address this question, let us first consider the Fantasy Fifth’s narrative placement more rigorously. Matthew Bribitzer-Stull (2015, 102) observes that temporal coincidence of musical and narrative elements provides a necessary condition for associative signification. In my previous examples, the progression accompanies an entrance into the films’ fantasy diegesis. Even more strategically, Javier Navarrette’s music to Inkheart positions each triad to reinforce a move from a quotidian world (the titles) to one of fantasy (where characters can read other characters out of books). In Inkheart’s prologue, a Fantasy Fifth-laden passage is initiated at the fantasy-beckoning dialogue “Once upon a time” (0:00:56). As in Night at the Museum, these preluding cells build to a climactic token of the progression aligning i to the appearance of the “Inkheart” title and IV to the title’s subsequent dissolution (Appendix – 3). Netflix’s The Dragon Prince provides another example of targeted IV alignment.15 In this example (Appendix – 4), the IV triad is synchronized to the narrator’s pronouncement of “Xadia,” the series’ magical land (0:29). Swiftly overwritten by VI’s lowered $$\hat6$$, the IV’s raised $$\hat6$$ radiates Xadia’s alterity.16

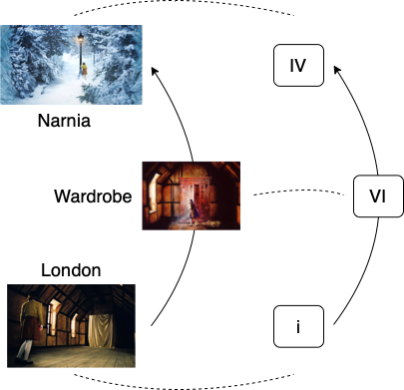

A final, exceptionally robust example lies in Harry Gregson-Williams’ score to The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. Its use of the progression is illustrative on several levels. Foremost is the narrative location of its first appearance: Lucy’s discovery of the magical wardrobe and first passage into Narnia (Appendix – 5). In this scene, Gregson-Williams precedes the standard i – IV relationship with an interpolating version, i – VI – IV (0:11:58). Murphy (forthcoming) observes that the VI–IV progression (M89M∅) – here nested within the Fantasy Fifth – has come to underlie heroism in recent screen music. One might read the interpolation to foreshadow the protagonists’ heroic adventures awaiting them across the threshold.

This bit of a semiotic combinatoriality aside, the interpolated VI’s effect is twofold. First, by preceding the IV with a diatonic triad, the introduction of chromaticism at IV is rendered more unexpected and its otherness foregrounded. Secondly, the VI creates an intervening step (from $$\hat5$$ to raised $$\hat6$$ along the Fantasy Fifth trajectory), much as the wardrobe is an intervening conduit between worlds. Ascent and expansion become all-the-more pronounced by the intervening $$\hat6$$. Following Brower’s conception of intervening harmonies as waypoints along a metaphorical path, Clark observes that the path image schema provides an enabling similarity between tonal and narrative motion (2018, 110). Here we may find an analogy between narrative and tonal paths: Lucy’s passage through the wardrobe to Narnia, and the progression’s passage to IV through VI (Figure 4). In both cases, a seemingly commonplace object mediates the traversal from “home” to “other.”

This interpolation also proposes an answer to the lingering question of the preceding section, one that bears witness to the Fantasy Fifth’s unique voice leading properties. As Lucy crosses the threshold into Narnia, the common tone’s retention underscores a functional recontextualization mirroring that of a protagonist transported. All three triads retain $$\hat1$$, recontextualized chord by chord. Following Daniel Harrison’s approach to scale degree function (1994, 101–102), it is first the base, then agent, and finally the associate of successive chords). Like the common tone, the protagonist becomes transformed while remaining the same individual across this divide. Neither the m1M∅ nor m4M∅ – nor any other TTPC invoking the image schemas discussed above – contains this property of common tone recontextualization.17

A hallmark of fantasy realms such as Narnia is their intermixing of worldly and magical elements. If the IV triad represents a destination into fantasy, and if the common tone stands for a protagonist, then one might read this intermixture into the other two scale degrees of the Narnia triad. The raised sixth, overcoming through chromatic alteration its natural tendency to descend, gains an inertial charge representing an ordinary world imbued with magic and undiscovered potential. Just as otherworldly elements become highlighted by the normal elements from which they issue, the raised $$\hat6$$ is, in Harrison’s sense, a projection of the diatonically normative $$\hat4$$, a chromatic alteration tethered to a diatonic root. These scale degrees, like the worlds they accompany, blend the expected and unexpected, the diatonic and chromatic, and the individual who navigates between them.

4. Functional Multivalence: Arrival at the Unexplored

The reader will note that I have not yet clarified the tonal function of the IV triad. As Lehman observes, a noteworthy feature of the neo-Riemannian F is that its triads are often functionally underdetermined (2018, 134–135). With the prevailing minor tonicity on display in the above examples, I would submit that this latent potential for tonal ambivalence has nowhere to go but the second triad. Let us return to the Night at the Museum title cue (Figure 3). The dominant arrival (notated m. 2), subtonic half-cadential syntax (mm. 9–10), and primacy of the G-minor triad (here and since the film’s opening) leave little doubt that this passage is definitively in the minor mode. But there are ways in which the subdominant triad could feel rather tonic-like. It is approached by an ascending melodic fourth, which is a strong cue for dominant-to-tonic motion (see Vos 1999, 4). The preceding measure behaves like a rhythmic anacrusis, highlighting the IV’s metric and agogic stress as a moment of arrival. It is also at the IV chord that our metric reorientation to triple meter is actualized, charging this moment with another sense of beginning. Finally, let us return to Nobile’s conception of function-as-progression, introduced above in the discussion of the Saint-Saëns. Tonic tends to progress to subdominant function, and the repeated basic idea places a potent subdominant sonority – a Neapolitan – where the IV triad had been. To the extent that this passage foregrounds a progression from IV to *fII, the move to the latter could be heard to charge the former with a before-the-subdominant functional quality – that is, a sense of relational tonic-ness. Again, by broader context the IV is unambiguously a modally mixed subdominant triad. By Nobile’s conception of tonal function as chord category, it is a “categorically” subdominant triad. But by inviting simultaneous, if less convincing, senses of tonic beginning, the triad could invite what Michael Spitzer has characterized as a “bifocal flicker” between interpretive states (Spitzer 2006, 100–101).18 This flicker, in turn, resembles a familiar simultaneity central to fantastic beginnings: the coincidence of having left the familiar (subdominant) and having arrived (tonic) at the new and unexplored.

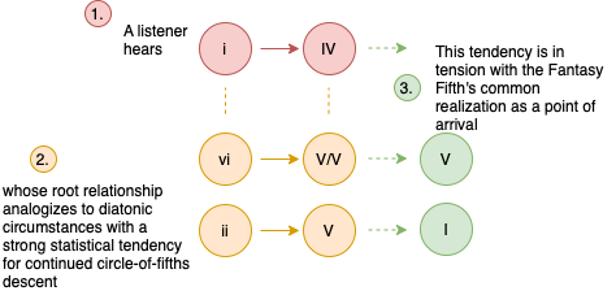

Extrapolating from this example, many of the other cases surveyed above present the IV triad as a melodically lengthened event, charging it with varying degrees of agogic arrival and concomitant dissipation of rhythmic energy. Likewise, in all except one, IV comes at an unambiguous grouping boundary. Yet there is a case to be made that, accustomed to the normatively pre-cadential nature of a minor-to-major progression by fifth, the major triad of any F(m) progression in some sense “intends,” in the sense of Steven Rings’ notion of tonal intention (2011, 105–106), another fifth related triad above it. Figure 5 illustrates this latent “almost-there” status of the major triad when heard in a diatonic circle-of-fifths context. When such further continuation does not materialize after the veridically encountered IV triad, one can entertain a flicker between mobility and stasis again reminiscent of having simultaneously departed and arrived.

Unlike the subdominant-tonic flicker in the Night at the Museum cue, the above analogy alternatively suggests a flicker between IV’s categorical status as subdominant and its circle-of-fifths tendency to behave like a locally dominant triad. A final instance of multivalence evidences a similar tension between subdominant and dominant function, this time between progressive and syntactic views. John Williams’ “Force” theme is presented in full phrase-structural syntax at the infamous “binary sunset” cue in Star Wars – Episode IV: A New Hope (Appendix – 6). Much has been written on this theme’s gradual unfolding and the attendant mythic qualities of its signification (see, for instance, Buhler 2000). In this cue, the protagonist Luke, having just been told he must remain on his home planet Tatooine for another year, gazes out at the sky and its radiant double suns setting in the distance. The IV triad materializes as we – and Luke – have the suns in full view, a sudden and expansive display of what is unmistakably a symbol for the Star Wars Universe’s otherness. As the image shifts to the confined protagonist’s longing to transcend his narrative circumstances, diatonic reassimilation of the modally mixed IV palpably reflects that his dream is out of reach.

The periodic syntax of this phrase makes the IV triad unmistakably half-cadential, charging it with the positionality of a “syntactic dominant.” This notion of IV-as-dominant is not without controversy but well-established in other tonal idioms (Nobile 2016, 155). What is perhaps less than usual here is that such major IV half-cadential function would follow a prolonged minor tonic triad.19 20 In this particular sequence there is no preceding tonal departure from tonic to render this half cadence truly half-cadential; rather, the saturating three measures of tonic prolongation defer tonal departure to the half cadence, after which an anacrusis to the continuation completes the i – IV – V – i circuit. Thus, the IV chord occupies the progressive tonal function of a subdominant while rhetorically and syntactically behaving like a dominant arrival. This is positional multivalence at fantasy’s finest: departure and arrival comingle at this moment just as Luke’s longing for more, and realization of his confinement, are in tension with one another. Thus, rather than being “about” the otherness of the binary suns, the IV triad accompanies a worldly and deeply human sense of fantasy.

Conclusion: Fantasy in the Normal World

In all the films above, the Fantasy Fifth is a recurrent motive with an unambiguous tonic extending beyond the progression’s local context. But to restrict analysis to these cases would be to dismiss the comparatively large swath of Classical Hollywood underscore that is both athematic and tonally ambiguous. I therefore conclude this vignette with an example that can generalize beyond the existing instances, one in which a “roving tonality” (Lehman 2018, 8, 206) central to the Hollywood idiom provides an equal context for observing this progression’s associativity. Hans Zimmer’s music to The Last Samurai provides such a passage (Appendix – 7). The final battle scene depicts the slaughter of the samurai and its protagonist leader, Katsumoto, at the hands of the Imperial army. As Katsumoto draws his last breaths (2:14:45), he gazes upon a cherry tree, remarking, “Perfect – they are all perfect.” This moment of insight is narratively significant: it represents a departure from his beliefs that the perfect blossom is exceedingly rare, and that the pursuit of such perfection is a life well spent.

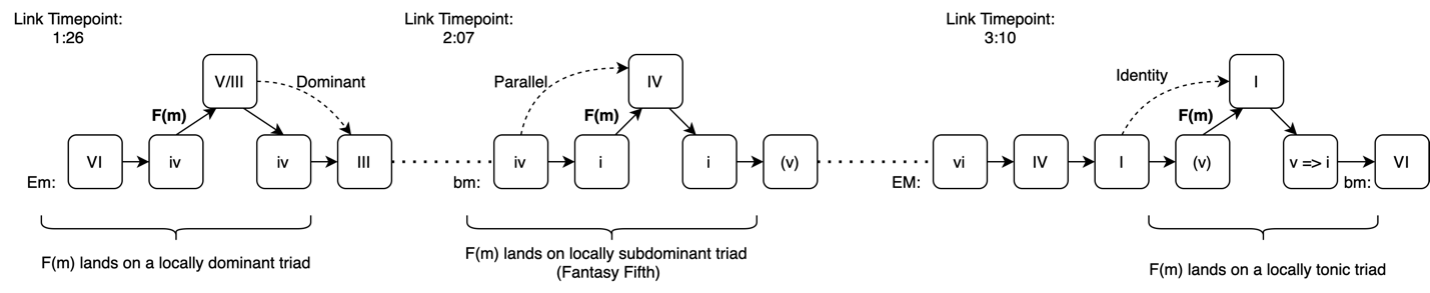

The music accompanying this battle scene contains three F transformations of the minor-to-major variety, and Figure 6 displays an account of their local harmonic contexts. Only the second of these F(m) transformations unambiguously leads from a local minor tonic to a modally mixed subdominant, thereby qualifying as a tonic-departing Fantasy Fifth; its two flanking F(m) transformations charge their respective major triads with the other two functional qualia – dominant and tonic, respectively – owing to local tonal interpretations of iv – V/III and v – I.21 Fittingly, the second presentation is the one to which the cherry blossom shot is aligned. By sandwiching a Fantasy Fifth between these alternate variants, this passage not only demonstrates the supreme tonal flexibility of the Far Fifth transformation in tonally mobile contexts, but it points to the seeming importance of veridically encountered tonic departure, relative to impending or actual (albeit fleeting) tonic arrival, to accompany a narrative encounter with fantasy. In short, it dissociates the Fantasy Fifth from related but non-referential progressions and narrative moments.

While this film does not invoke fantasy elements in a generic sense, Katsumoto’s moment of enlightenment nevertheless aligns with the definition of fantasy induction put forth in this vignette. Here, the traversed divide between the worldly and the otherworldly is that between life and death, and the attendant encounter with the wondrous is not with an object of fantasy but with a fantastic interpretation of an earthly impossibility: finding a single perfect cherry blossom, as Katsumoto recounts earlier in the film, is practically impossible.

To conclude, this vignette has presented a series of case study films in which tonal progression from a minor tonic to its major subdominant triad accompanies narrative encounters with fantasy. These uses have consistently foregrounded the IV’s raised sixth scale degree, especially through local juxtaposition against lowered $$\hat6$$. Together with narrative alignments, this raised quality has invited embodied connections between voice leading and tonal structure on the one hand and fantasy induction on the other; and a functional multivalence at this triad can be seen to mirror the positional indeterminacy of having arrived in a new and wondrous place – a hearing only possible when the minor triad of the F retains its categorical tonicity. Though admittedly my reading conceives of fantasy in a broad sense, this breadth is intentional, in the hopes that future exploration of this fascinating corpus will discover additional connections to this progression’s use. Existing inventories of the related F progression leave little doubt that there is much still to be explored with the Fantasy Fifth in Hollywood film music.

References

Bharucha, Jamshed. “Tonality and Expectation.” In Musical Perceptions, edited by Rita Aiello and John Sloboda, 213–39. Oxford University Press, 1994.

Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew. Understanding the Leitmotif: From Wagner to Hollywood Film Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Brower, Candace. “A cognitive theory of musical meaning.” Journal of music theory 44, no. 2 (2000): 323–379.

———. “Paradoxes of Pitch Space.” Music Analysis 27, no. 1 (2008): 51–106.

Buhler, James. 2000. Star Wars, Music, and Myth. Music and Cinema. Ed. by James Buhler, Caryl Flinn, and David Neumeyer. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press, 33–57.

Chattah, Juan. “Semiotics, Pragmatics, and Metaphor in Film Music Analysis.” Dissertation, The Florida State University, 2006.

Cian, Luca. “Verticality and Conceptual Metaphors: A Systematic Review.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 2, no. 4 (October 2017): 444–59.

Clark, Ewan Alexander. “Harmony, Associativity, and Metaphor in the Film Scores of Alexandre Desplat.” Thesis, Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington, 2018.

Clercq, Trevor de, and David Temperley. “A Corpus Analysis of Rock Harmony.” Popular Music 30, no. 1 (January 2011): 47–70.

Cohn, Richard. “Peter, the Wolf, and the Hexatonic Uncanny.” In Tonality 1900–1950: Concept and Practice, edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheidler, and Philip Rupprecht, 47–62. Stuttgart: Franz Schneider Verlag, 2012.

———. “Uncanny Resemblances: Tonal Signification in the Freudian Age.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57, no. 2 (August 1, 2004): 285–324.

Cook, Nicholas. “Theorizing Musical Meaning.” Music Theory Spectrum 23, no. 2 (2001): 170–95.

Harrison, Daniel. Harmonic Function in Chromatic Music: A Renewed Dualist Theory and an Account of Its Precedents. 1st edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Hedblom, Maria M., Oliver Kutz, Rafael Peñaloza, and Giancarlo Guizzardi. “Image Schema Combinations and Complex Events.” KI – Künstliche Intelligenz 33, no. 3 (September 1, 2019): 279–91.

Heine, Erik. “Chromatic Mediants and Narrative Context in Film.” Music Analysis 37, no. 1 (2018): 103–32.

Huron, David. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Illustrated edition. Cambridge, Mass: Bradford Books, 2008.

Johnson, Mark. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Lehman, Frank. Hollywood Harmony: Musical Wonder and the Sound of Cinema. Oxford University Press, 2018.

London, Justin. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Mirka, Danuta. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, edited by Danuta Mirka, 1–60. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Murphy, Scott. “Abundant Novelty of Antitonic Harmony in the Music of Nikolai Myaskovsky.” In Analytical Approaches to 20th-Century Russian Music, edited by Inessa Bazayev and Christopher Segall, 1st ed., 32–53. New York : Routledge, 2020.

———. “Scoring Loss in Some Recent Popular Film and Television.” Music Theory Spectrum 36, no. 2 (2014b): 295–314.

———. “The Major Tritone Progression in Recent Hollywood Science Fiction Films.” Music Theory Online 12, no. 2 (May 2006).

———. “Tracking Progressions of Heroic Chord Progressions in Recent Popular Screen Media.” In Music Analysis in Film: Counting up the Score, edited by Frank Lehman. Routledge, Forthcoming.

———. “Transformational Theory and the Analysis of Film Music.” The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies, 2014a.

Nobile, Drew. “Harmonic Function in Rock Music.” Journal of Music Theory 60, no. 2 (October 1, 2016): 149–80.

Obluda, Daniel. “Topics in Hollywood Scores: Using Topic Theory to Expand on Recent Neo-Riemannian Analyses of Film Music.” Dissertation, University of Colorado Boulder, 2021.

Rings, Steven. Tonality and Transformation. Oxford Studies in Music Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Spitzer, Michael. Music as Philosophy: Adorno and Beethoven’s Late Style. Illustrated edition. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Vos, Piet G. “Key Implications of Ascending Fourth and Descending Fifth Openings.” Psychology of Music 27, no. 1 (April 1, 1999): 4–17.

White, Christopher Wm., and Ian Quinn. “Chord Context and Harmonic Function in Tonal Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 40, no. 2 (2018): 314–37.

Zbikowski, Lawrence Michael. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. AMS Studies in Music. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Notes

- While the examples surveyed in this vignette have variable surface realizations, the relevant properties discussed in connection to this voicing nevertheless generalize to those examples.

- Murphy (forthcoming) further disaggregates all the transpositionally related m5M∅’s of a given key with a subscript following the first triad to indicate its distance from the root. Thus, the Fantasy Fifth’s full label would be m05M∅ to index that the first triad is the tonic. For notational ease, this 0 can be omitted.

- Here I follow Jamshed Bharucha (1994), and later David Huron’s (2006, 224–225), distinction between veridical and schematic expectations, in which the former is informed by previous hearing and the latter by semantic knowledge of style.

- Despite that sentence presentations do not cadence, the slow tempo of this excerpt seems to collude with these features to reinforce the “dominant arrival” quality of this moment by positioning the IV at the edge of the so-called “psychological present” (London 2012, 30), at which point a syntactic resting point such as a half cadence would be expected.

- I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing me toward Nobile’s relevant distinctions between categorical, progressive, and syntactic definitions of tonal function, which are taken up later in this vignette.

- The tonic triads of measure seven would have needed to be submediants to carry the sequence to the half cadence.

- Similarly, while Obluda identifies two concert works containing F that suggest connections to nature – F(m) in Debussy’s La Mer, and a repeated V–ii progression (i.e., F(M)) in Sibelius’s purportedly nature-invoking Symphony No. 1, first movement, explicit allusions to fantasy elements and F(m) are likewise absent from his historical inventory.

- I am not yet asserting the tonal markedness of the raised sixth degree, though I believe it certainly draws further attention to the upward gestalt; tonal markedness becomes relevant when we consider the center-periphery and container schemas below.

- Two such instances come from the opening of Night at the Museum (0:00:42) and The Dragon Prince (Episode 1, 00:52), in which an upward-panning camera and a dragon ascending from earth to space, respectively, draw attention to the shared ascent.

- Here, Lehman’s term “Far” finds a nice metaphorical resonance with uses of the Fantasy Fifth to evoke large distances. Moreover, Clark’s notion that TTPC-is-expanding-container may provide a conceptual explanation for Obluda’s recognition that F(m) is well-positioned to evoke transcendence.

- For instance, both of Cohn (2004)’s hexatonic pole and Murphy (2006)’s major tritone progression evoke otherness with 3 novel scale degrees.

- IV similarly calls forth a Dorian idiom in Inkheart’s prologue (0:00:56). It is also metrically and agogically accented, a recurrent feature elaborated below.

- Even within a Dorian context, the i-IV progression is something of a minor-to-major one-of-a-kind: it is the only naturally occurring minor-to-major progression by fifth, while all other root distances have multiple naturally-occurring progressions.

- Hedblom, Kutz, Peñaloza and Guizzardi (2019) provide a thorough account of these developments.

- I thank Scott Murphy for bringing this example to my attention.

- y my reading, Wiedmann’s use of the IV triad comes to represent Xadia’s unseen “primal energy,” a use that finds an interesting parallel to John Williams’ feature of the progression in “The Force” theme from the Star Wars series, to be discussed below.

- Here, of course, I am referring to parsimonious voice leading contexts, for which all the present examples qualify.

- Spitzer’s conception of tonal bifocality is intimately bound up with the Hegelian dialectic and Adorno’s notion of “Schein,” both of which involve reckoning with the coexistence of seemingly incompatible states. Schein’s flicker has the arresting quality that characterizes arrival into fantasy. This multiplicity also traces important roots to David Lewin’s application of Husserlian phenomenology, in which multiple (and mutually exclusive) perceptions can coexist.

- Plagal half cadences by contrast usually involve tonic and subdominant triads of the same mode.

- There is a case to be made that in contemporary idioms such as popular and rock music, any IV triad immediately following a minor tonic, regardless of its syntactic function, is something of a statistical exception rather than rule. For instance, endorsing a progressive view of tonal function and using the McGill-Billboard Corpus, Chris White and Ian Quinn demonstrate that, statistically speaking, minor tonics in popular music tend to progress to triads of an opposing function they label “W” rather than to chords within the tonic triad’s functional category (“X”), of which IV is also a member. This is not to suggest such progressions never happen. On the contrary, see their Example 15 on pp. 326 for one of many counterexamples involving the so-called “Dorian shuttle.” A cursory review of other non-classical corpora, such as Trevor de Clercq and David Temperley’s (2011) Rolling Stone corpus, shows that i–IV is rare in their rock sample as well, comprising less than seven percent of bigrams leading from a minor tonic.

- While the first F(m)’s major triad feels progressively dominant – V/III progresses to the relative major after an intervening chord – the third instance is more complex. A local vi–IV–I progression in E major primes the ensuing E-major triad of its F(m) to sound tonic-like. But the following B-minor triad leads to G major, an L transformation that would seem to retrospectively charge the B as a local center. If this retrospection propagates further back, the F(m) begins to feel like a i – IV progression as before.