James S. MacKay

Abstract

The first movement of Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet in B minor, op. 64, no. 2, has long resisted conventional sonata-form analysis. A sense of unrest characterizes its musical journey: ambiguous, incomplete, or seemingly misplaced formal units hold sway as the exposition unfolds, setting a turbulent tone that persists throughout the development section. Subsequently, rather than establishing formal clarity in the recapitulation, Haydn further dissolves the musical material until it stalls completely, resuming its motion with great difficulty as the movement concludes.

This study, drawing upon previous discussions by William Caplin (1998), Mathieu Langlois (2010), and Matthew Hall (2019), presents an in-depth analysis of this movement, primarily using Caplin’s theory of formal functions, James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Sonata Theory (2006), and Janet Schmalfeldt’s becoming (2011). The blending of disparate analytical methods provides a framework to illustrate how Haydn both articulates and stretches the boundaries of sonata form.

View PDF

Return to Volume 36

Keywords and Phrases: Formenlehre, Sonata Theory, Becoming, string quartet, Haydn, Sonata form

Introduction

The opening movement of Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet in B minor, op. 64, no. 2 (1790) has long resisted analysis using conventional theories of sonata form. After beginning with a hint of D major (recalling the earlier quartet in B minor, op. 33, no. 1, as various authors have noted1), a sense of unrest persists throughout the movement’s formal journey: a series of ambiguous, incomplete, or seemingly misplaced form-functional units articulate the exposition’s move to the relative major. The main theme is already formally unconventional according to Caplin’s theory of formal functions, seeming to comprise a pair of antecedent phrases. Further structural ambiguity in the subordinate theme creates an even greater formal challenge. The stormy development section downplays its concluding dominant, ending on an inverted diminished seventh chord rather than with an extended dominant pedal. Finally, rather than achieving tonal and thematic clarity in the recapitulation, the thematic material gradually dissolves until the movement stalls completely, resuming its motion as if with great difficulty as it reaches its terminal cadence.

This study, building upon previous discussions by William Caplin (1998), Mathieu Langlois (2010), and Matthew Hall (2019), presents an in-depth formal analysis of the opening movement of op. 64, no. 2. I will interpret its challenging design by combining Caplin’s theory of formal functions with Janet Schmalfeldt’s “form as process” (2011), along with insights from Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory (2006). As this study will demonstrate, a blending of disparate analytical methods is the most effective way to elucidate the complex yet satisfying logic by which this movement articulates and stretches sonata form’s boundaries.

1. Exposition

Hans Keller’s insightful (though brief) discussion of this movement (Keller 1986, 150–152) describes it as a daring work whose “mature adventurousness” is in evidence with every motive, phrase, textural innovation, and modulation, an observation with which Reginald Barrett-Ayres concurs, singling out the subordinate theme’s chromatic excursion for its boldness (Barrett-Ayres 1974, 252). Caplin devotes considerable space and analytical attention to the movement’s exposition and recapitulation (Caplin 1998, 104, 116, 174–177) in a detailed analysis that has influenced Langlois (2010) and Hall (2019).

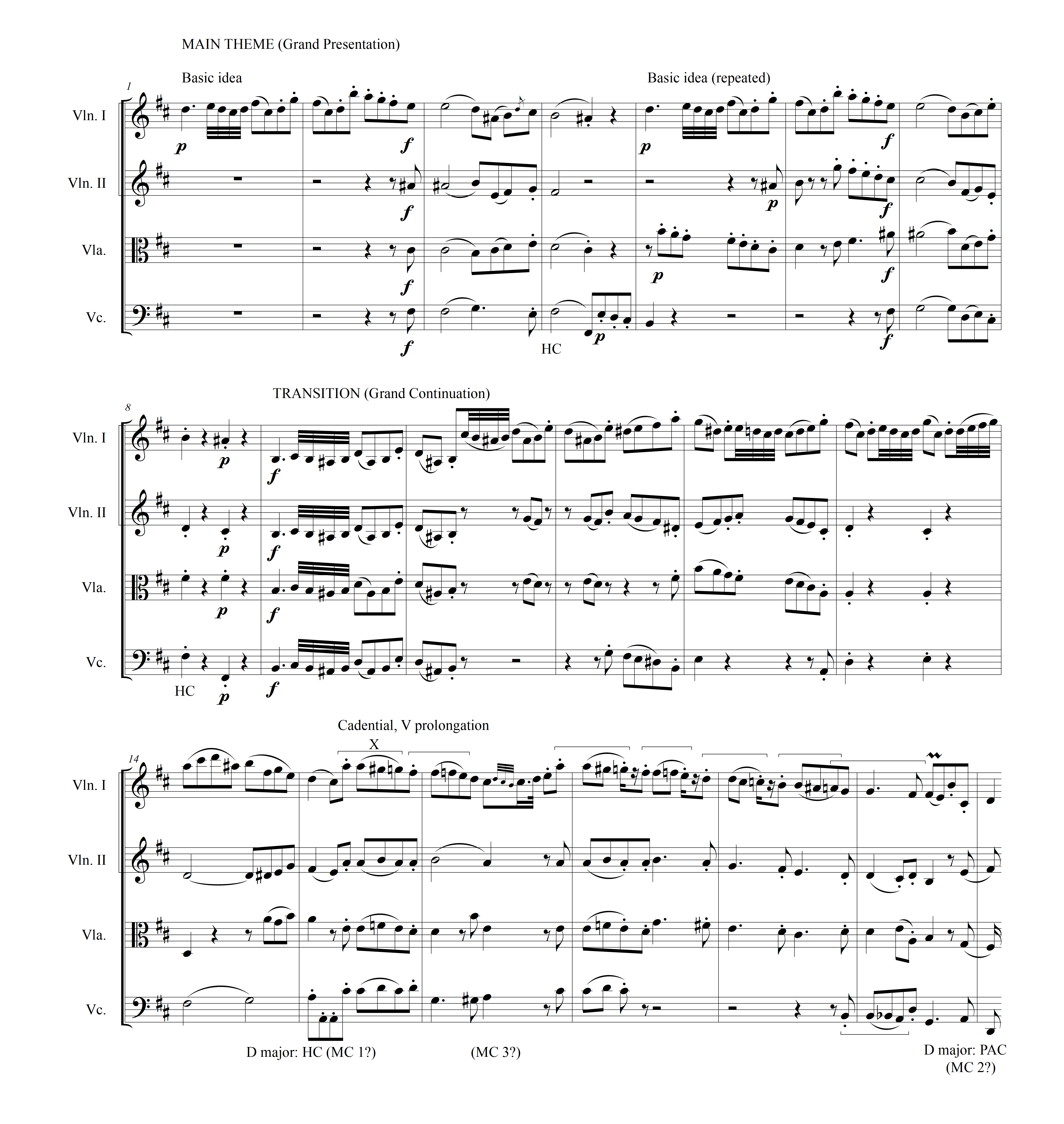

The opening twenty measures, comprising the home key’s establishment and the modulation to the subordinate key, exemplify the formal challenges involved (Example 1). The initial four measures form an antecedent phrase that arrives on a dominant harmony. One would expect a consequent phrase to follow, but measures 5–8 present instead an elaborate restatement of the antecedent phrase, again ending on a dominant harmony. Following this unusual tonal goal, a variant of the opening incipit, stated in unison in a lower register, returns in measure 9 to provide a confirmation of tonic harmony that was absent in the opening four measures.

This passage creates multiple possibilities for interpreting the main theme’s concluding cadence. Much like the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A minor, K. 310, I, an emphatic dominant in measure 8, embellished with a cadential six-four, leads to a tonic chord on the downbeat of measure 9, with a registral shift that complicates the identification of the main theme’s conclusion. As Burstein (2014, 221) illustrates, the “slippery” formal juncture in K. 310 could imply a half cadence (HC) in measure 8, an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) in measure 9, or a disrupted ending, in which a new phrase begins before the prior phrase has reached a “syntactically proper conclusion” (Burstein 2014, 218). Op. 64, no. 2 presents a similarly multifaceted closing gesture, since either the embellished dominant chord midway through measure 8 or the tonic chord on the following downbeat can be construed as the main theme’s harmonic goal. As such, Haydn’s main theme exemplifies Burstein’s “slippery” criteria better than K. 310. This tonally ambiguous eight-measure theme, whose beginning does not clearly establish the home key and whose ending admits of multiple cadential interpretations, sets the formal tone for the entire movement.

Each formal interpretation of this complex boundary has its advantages and disadvantages. If the dominant harmony in measure 8 is truly the main theme’s harmonic goal, the opening eight measures would form an “Antecedent-Antecedent” design. Although the opening measures follow a standard periodic design if the main theme ends with a PAC in measure 9, as Langlois (2010, 121) asserts, the disjunction in register argues against this interpretation. (Here, Burstein’s suggestion regarding K. 310 that the new beginning of measure 9 in some way disrupts the expected syntactical conclusion seems more apropos.) Caplin (1998, 177) proposes both of these cadential solutions due to the passage’s inherent ambiguity but leans toward the PAC in measure 9 as the main theme’s goal harmony, eliding with the transition’s onset.

The “Antecedent-Antecedent” design of measures 1–8 is surely an unusual theme type, especially for a main theme, where both tonal and form-functional clarity are paramount. However, Schmalfeldt’s “form as process,” i.e., the concept of becoming (Schmalfeldt 2011), provides a solution for this analytical impasse. If measures 1–8 function as the beginning of a longer unit, their motivic shape suggests an expanded presentation phrase, for which the transition (measures 9–20) supplies an equally expanded continuation. Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 77–80) use the terms “grand antecedent” and “grand consequent” to describe the common “statement-counterstatement” strategy for main theme plus transition:2 the initial thematic content of op. 64 no. 2, in emulation of their terminology, suggests a “grand presentation” followed by a “grand continuation.” The “grand sentence” that results (measures 1–20) encompasses both main theme and transition. Though it is a stretch to claim that the main theme “becomes” the transition in its entirety, the “grand presentation” of measures 1–8 does begin the thematic processes that will lead to the transition/continuation and its tonally destabilizing move to the subordinate key.3

Beginning in measure 9, prior material from the “grand presentation” phrase is fragmented and developed in the manner of a continuation phrase, while a modulation to the relative major destabilizes the home tonality (first confirmed with a HC in measure 15). These measures illustrate the similarity of procedure between continuation phrases and transitions: fragmentation and development of prior material are common to both formal functions. Thus, a dual reading of the opening 20 measures as either main theme plus transition, or as a 20-measure main theme in which the “grand continuation” function retroactively serves as transition (“grand continuation”⇒transition) is analytically tenable. An extended dominant pedal in the subordinate key, featuring a descending chromatic motive (labeled Motive X on the score) ensues in measures 15–19, leading to a PAC in measure 20 that brings this expanded sentence to a close.

Measures 9–20 have elicited many different formal interpretations, since they contain at least two viable locations for the exposition’s medial caesura (henceforth MC).4 If the transition modulates, the caesura is most frequently a HC in the subordinate key (Hepokoski and Darcy’s “first-level default,” m. 15 in this movement). It may also be a PAC in the subordinate new key (Hepokoski and Darcy’s “third-level default,” m. 20 in this movement).5 Since Caplin (1998, 131–135) asserts categorically that transitions must end on a dominant chord, he chooses the earlier MC option as the transition’s conclusion out of analytical necessity, labeling measures 15–20 as Subordinate Theme 1 (Caplin 1998, 116, Example 8.15). Though the segment’s concluding PAC in measure 20 makes such an interpretation possible, it remains problematic because the passage, despite its formal organization as a compressed sentence (Caplin 1998, 114–115), may be too brief to be heard as a viable theme. Moreover, the prolongation of V harmony suggests that measures 15–20 are a natural extension of the preceding formal unit; thus, this phrase continues to evoke a transitional character.6 As such, the PAC in the relative major in measure 20, which opens up rhetorical space for a change in musical character, is the better candidate for the MC.

On a first hearing, this emphatic arrival on the tonic of D major may be mistaken for the exposition’s final structural cadence, signifying the “essential expositional closure” (EEC) that concludes its harmonic motion.7 Insofar as measure 20, with its PAC in the subordinate key, completes the standard harmonic trajectory of a minor-mode sonata exposition, a codetta could follow, concluding a musically satisfactory (if somewhat brief) exposition. At first, measures 20–23 seem to be doing exactly that. An omnipresent tonic pedal—a hallmark of closing rhetoric—underpins the proceedings, justifying Caplin’s designation of these measures as a “false closing section.”8 Once this material leads to additional phrases, however, the cadence of measure 20 stands revealed in retrospect as a III:PAC MC rather than an EEC. This interpretation elicits another application of Schmalfeldt’s “becoming”: if EEC⇒MC, then, by extension, closing section⇒subordinate theme.

Measures 20ff. unfold in a loosely sentential design. The double statement of melodic material in measures 20–21 suggests a concise presentation phrase, while its fragmentation into smaller units in measures 22–25 provides a continuation that seemingly prepares for another PAC in D major. The sought-after cadence is interrupted, however, by the sudden intrusion of D minor in measure 26. At this point, it is necessary to reconsider the preceding passage’s formal role. Recast as the first part of a longer formal unit rather than a complete standalone sentence, measures 20–25 now “becomes” the subordinate theme’s presentation phrase, while the ensuing “purple patch” of measure 26ff. (to borrow Donald Francis Tovey’s terminology9) complements this unit as its continuation⇒cadential phrase,10 thereby completing a fifteen-measure expanded sentence.

This continuation⇒cadential segment is a dramatic counterpart to the prior presentation phrase’s relaxed closing character. A forceful move from D minor to its Neapolitan (E$$\flat$$ major, or $$\flat$$II), whose brusqueness is exacerbated by parallel fifths in viola and Violin 2 (measures 26–27), leads to a series of hushed, mysterious ascending sixths. This unison passage, marked piano after an initial sforzando, effects a chromatic ascent—neatly balancing the chromatically descending “sighing motif” of measures 15–19—whose absence of harmonic support creates considerable tonal unease. Though one could infer specific harmonies in measures 28–30, the musical effect is a purely contrapuntal linkage between the Neapolitan chord of measure 27 and the dominant seventh of measure 31.11 The interrupted cadential progression of measures 23–25 resumes in measures 31–34, completing measures 26–34 as a greatly expanded cadential phrase. This richly ambiguous section concludes with an emphatic EEC in measure 34, whose harmonically conclusive status leads to a six-measure closing section. This concluding passage features frequent pizzicato as a coloristic variant. Its soaring melodic line in Violin I, expanding upward to a dizzying A6, was doubtless appreciated by Johann Tost, the Hungarian virtuoso violinist to whom Haydn dedicated the op. 64 quartets (Landon 1980, vol. 1, 655).

Though measures 9–34 strive to provide space for a conventional subordinate theme, this formal space never fully manifests itself, despite two possible medial caesuras in measures 15 and 20. As these brief points of rest create only momentary disruptions in the musical flow, this tonally and thematically elusive segment could reasonably be construed as an expansion section [Entwickslungpartie], which Jens Peter Larsen (Graue 2013, 9–10) describes as a developmental formal region mediating between the main theme and codetta.12 Hall (2019, 21) suggests analyzing measures 9–34 according to this enticing alternative to the expositional norm, but ultimately decides against resolving the formal ambiguity between a two-part exposition (with MC) and a three-part exposition (without MC) that the movement’s thematic processes create.

Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 53–60) describe this ambiguity as a “bait-and-switch tactic,” in which a composer lays the groundwork to introduce a subordinate theme but a suitable MC does not materialize. They use the term Transition⇒Fortspinnung (abbreviated TR⇒FS) to describe the formal unit that effects this musical change of heart. Granted, there is no meaningful Fortspinnung in these measures; rather, measures 9–34 comprise a succession of multivalent formal units whose knotty relationship to each other can be disentangled only with considerable difficulty. Moreover, these measures do provide at least two possible (if not incontrovertible) MC candidates, as noted above. Nevertheless, both Hepokoski and Darcy’s “bait-and-switch” and Schmalfeldt’s becoming hint at the sequence of musical events in this exposition, whose overall formal design shifts almost imperceptibly from one thematic strategy to another.

Due to its mixed formal strategies, this exposition benefits from the application of multiple theoretical models to parse its contents. Caplin’s theory of formal functions provides a framework to identify the movement’s individual phrases as initiating, middle, or concluding gestures, Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory provides criteria for musical punctuation (MC and EEC), and Schmalfeldt’s becoming explains the fluidity with which one formal segment of the exposition blends with another. It is a tribute to Haydn’s sophisticated formal sense that despite its fluid thematic layout, the exposition segments into a pair of complementary twenty-measure sections, creating at the deepest level of structure a perfectly regular two-part division.

2. Development

While the exposition and recapitulation of this movement have elicited considerable commentary, no author has analyzed its development section in detail, a lacuna that the current study will seek to fill. In many respects, the lack of attention given to this section by prior authors betrays its relatively clear formal design. Certainly, this development section poses fewer formal challenges than either the exposition or recapitulation, notwithstanding its challenging tonal language; its straightforward sequence of musical events balances the exposition’s formal complexities and ambiguities.

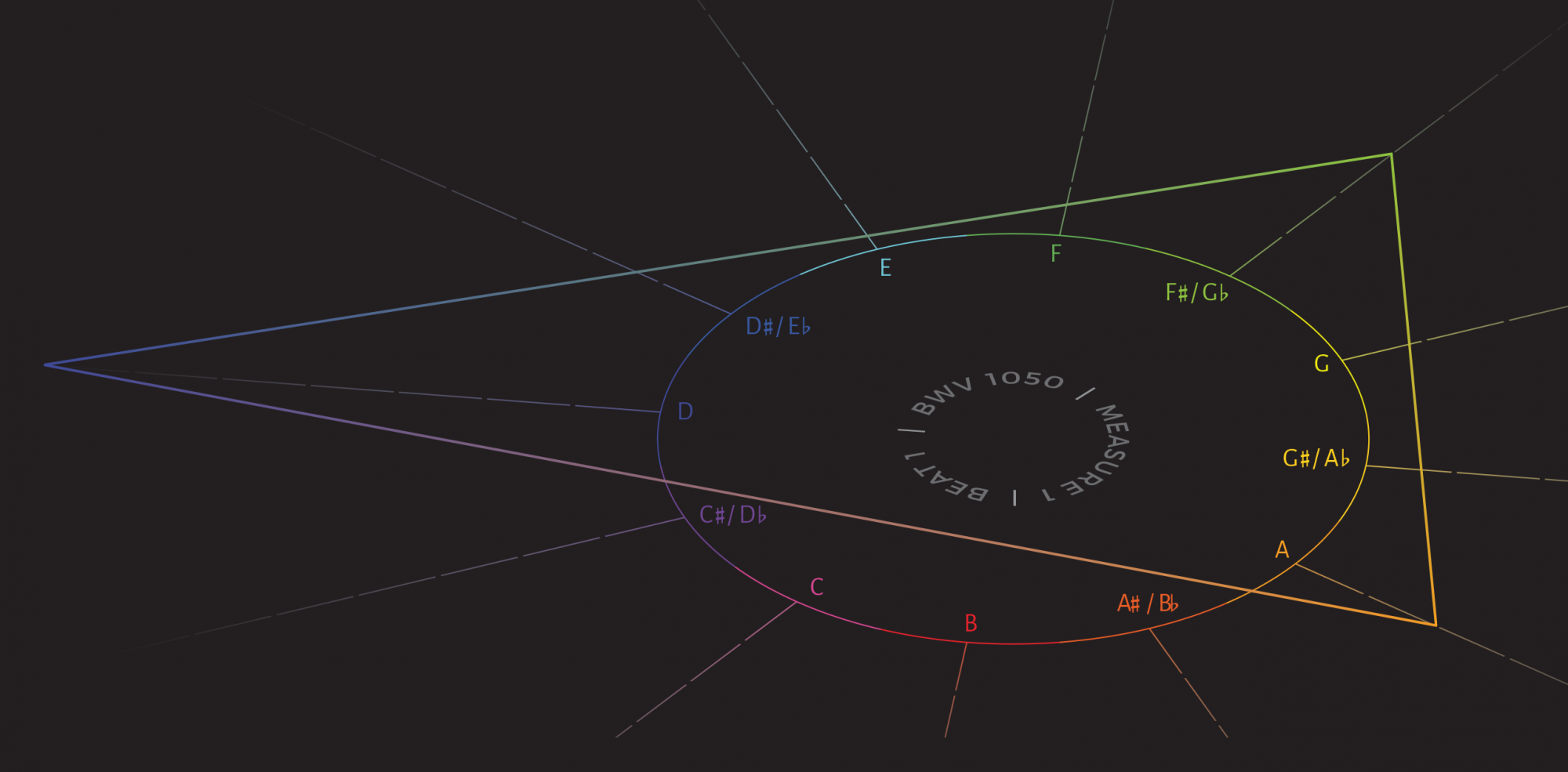

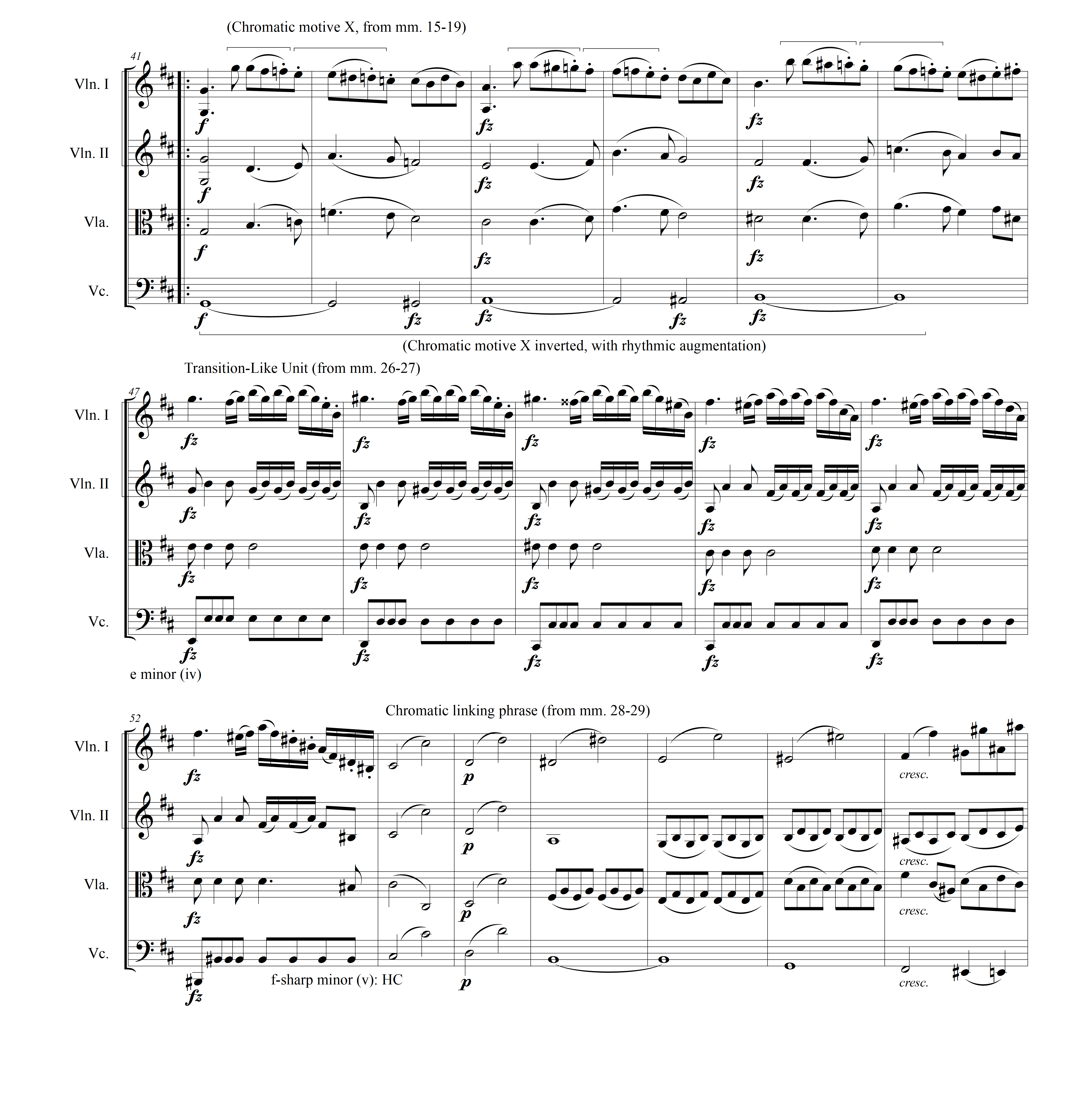

Haydn constructs the development around the most tonally nebulous melodic motives that had appeared in the exposition: the descending chromatic motive introduced in measure 15, the undulating arpeggio figure from measures 26–27, and the unison ascending leaps in long rhythmic values from measures 28–29. Haydn presents these motives in the order in which they appeared in the exposition, suggesting a rotational structure.13 As to the development’s formal design, following an initial phrase built from an ascending sequence, Haydn uses a “transition-like unit” (measures 47–58) as its centerpiece (Caplin 1998, 155), a formal label that suits the restless tonal and motivic quality of this segment.14

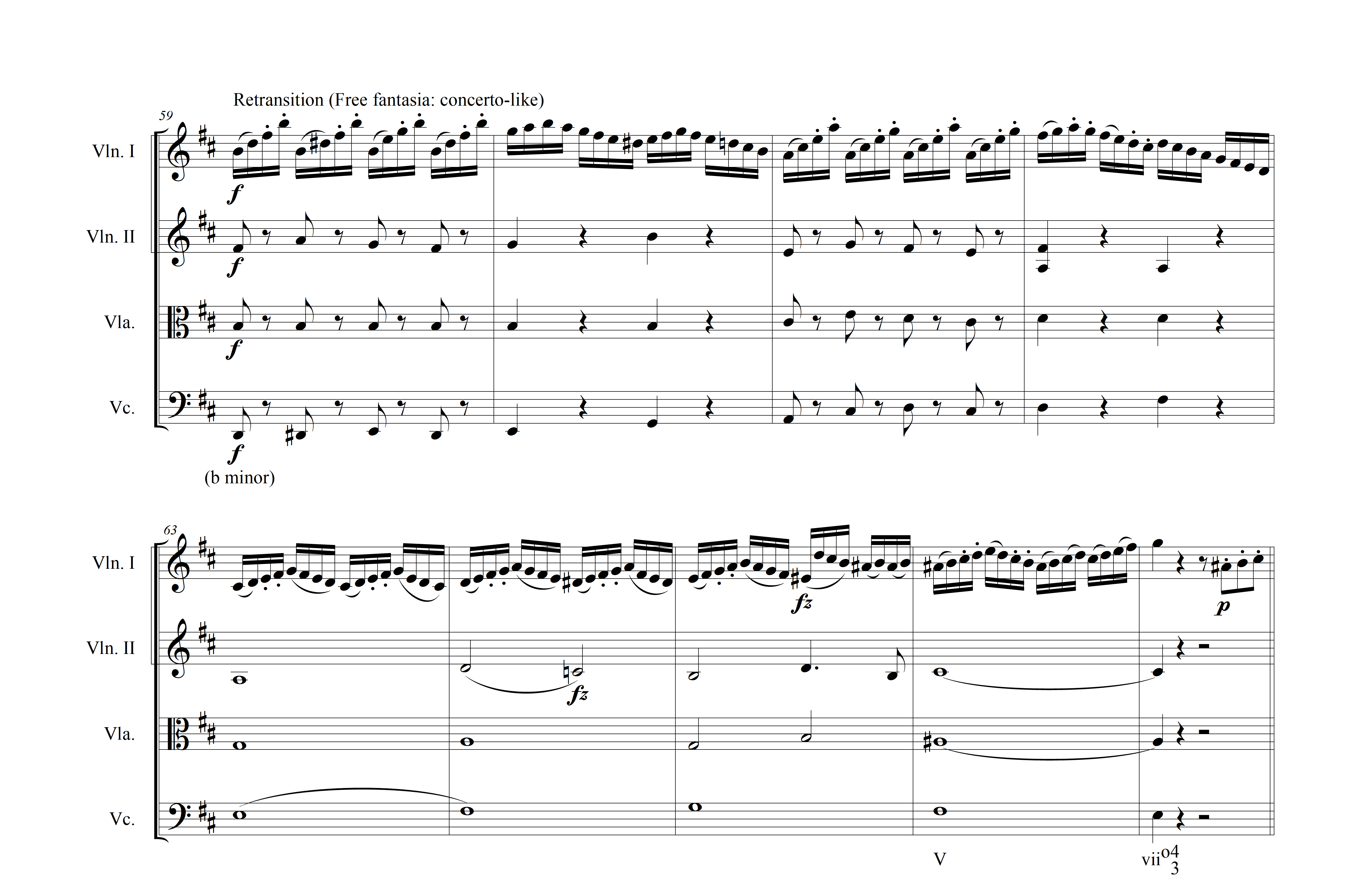

The development’s opening six measures set the tone: a chromatically descending motive in Violin 1 (Motive X from measures 15–19) combines with an ascending chromatic line in the cello, a gesture that comprises a free inversion and rhythmic augmentation of the violin’s melody. The transition-like unit then begins in measures 47–52 with undulating sixteenth notes, reminiscent of the “purple patch” from the subordinate theme (measures 25–26). After beginning in the subdominant key (E minor), Haydn modulates to the dominant minor (F$$\sharp$$ minor), confirmed with a HC (m. 53) to conclude this unit. In essence, the music moves from a transition-like unit (in place of a model-sequence core) from measures 47–53 through a chromatic linking passage in measures 53–58 to a retransition in the character of a fantasia from measures 59–67,15 with sixteenth-note arpeggios and scalar flourishes in Violin 1 that recall concerto figuration. This violin-dominant passage, foregrounded over a sparse accompaniment, provides an opportunity for virtuosic display—a musical nod toward Tost, perhaps—as the development modulates back to the home key. The dominant of B minor, which first appears in measure 66, moves quickly to an inverted diminished seventh chord, undercutting any sense of cadential arrival. After this understated dominant emphasis, a three-note scalar anacrusis at the end of measure 67 dovetails seamlessly with the recapitulation that follows (Example 3).

3. Recapitulation

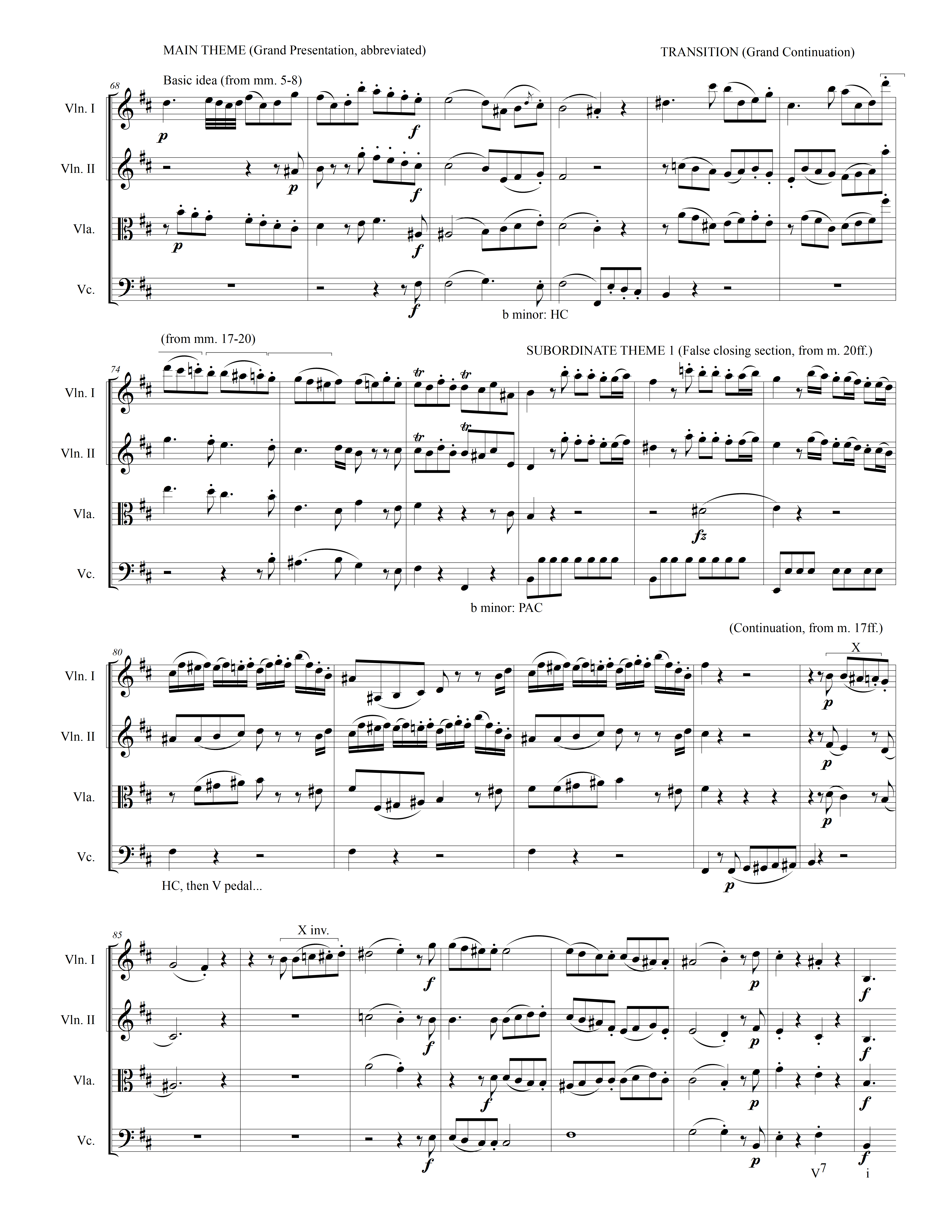

In Haydn’s practice, the recapitulation often serves rhetorically as a continuation of the development, reshaping thematic material rather than merely restating it.16 As Caplin (1998, 174–177) remarks, this particular movement’s reshaping results in a recapitulation that has minimal correspondence to the exposition. Though about 75% of the exposition does return in the recapitulation, much of this material is repurposed to different formal ends. The wholesale rethinking of material results in a recapitulation that seems minimally connected to the exposition, despite its reuse of virtually all of the exposition’s crucial material (Example 4).

As it is preceded by two measures of dominant function at the development’s conclusion, the main theme appears with greater tonal clarity in the recapitulation than it had in the exposition. By combining features of the exposition’s first and second phrases in measures 68–71 and adding the viola’s scalar countermelody from measure 5, Haydn confirms B minor from the outset. This single four-measure phrase is followed by a longer formal unit that features transitional rhetoric, suggestive of an enlarged continuation phrase, as it feints toward the subdominant, E minor.17 Although at first it develops the main theme’s incipit, this phrase soon uses the descending chromatic motive of measures 15–19 as it approaches its concluding PAC in measure 77 (which serves as the recapitulation’s i:PAC MC).

Here, as in the exposition, there is room for different formal interpretations. Measures 68–77 encompass the content of the main theme and transition, both in truncated form, thus accomplishing the thematic content of measures 1-20 in half as many measures. Caplin (1998, 176) tentatively labels this passage as the main theme (with a question mark), designating the theme’s partial reprise in measures 68–71 as an antecedent phrase and the following six measures as a continuation phrase while noting the derivation of 74–75 from measures 15–19, his Subordinate Theme 1. Langlois generally follows Caplin’s lead in this regard, subsuming the transition-like material of the recapitulation’s second phrase into the main theme. For Caplin, the PAC of measure 77 would mark this 10-measure segment as a reworking of the main theme, despite its incorporation of later motivic elements, with the transition yet to follow. However, since measures 68–77 display a similar thematic trajectory to measures 1–20, I interpret this segment as a greatly telescoped Main Theme/Transition formal unit, whose concluding medial caesura (PAC in the home key) opens up rhetorical space for the subordinate theme to return in B minor as the following phrases unfold.

Both Caplin and Langlois begin the transition at measure 77, with the “false closing section” material (Caplin 1998, 116) from measure 20, leading to the obligatory (for Caplin) HC of measure 80, and ensuing dominant pedal until the transition’s conclusion in measure 83. Though transitional rhetoric returns as this section unfolds, its designation as a subordinate theme in the exposition (following a PAC:MC) warrants the same formal label here. Haydn once again diverges quickly from the exposition’s content, tonicizing E minor en route to an extended dominant emphasis, made more emphatic by sixteenth-note figuration in Violin 1. To elucidate further this passage’s formal richness, the false closing module of measures 77–79 plus the ensuing dominant pedal in measures 80–83 could be construed as an expanded antecedent phrase, whose emphatic dominant arrival serves as the subordinate theme’s midpoint.

Measures 84–91 could have comprised an equally expanded consequent phrase to complete a 15-measure periodic design, but they instead display a developmental character, with the introduction and fragmentation of new material that recalls the chromatic motive from the exposition’s transition section. Overall, these measures give the impression of a theme losing its way, a technique that Haydn had previously used to great comic effect late in the second theme of his Symphony no. 60, Il distratto. There, the halting musical expression wittily depicts the lead character’s absent-mindedness, as H. C. Robbins Landon remarks (1978, vol. 2, 311–312). Here, however, there is no comedic intent, but rather, a hint of tragedy. Though Caplin (1998, 176) and Langlois (2010, 125) mark this phrase as Subordinate Theme 1, its halting delivery of thematic fragments suggests a middle function rather than an initiating one. Measures 84–91 create a continuation phrase to complement the antecedent phrase of measures 77–83, forming a 15-measure antecedent+continuation hybrid theme (Caplin 1998, 59–61).

The continuation phrase is introduced with an ascending chromatic slither in the cello. Violin 1 replies in contrary motion with Motive X, supported by Violin 2 and viola in tight three-part harmony, forming a series of descending parallel six-three chords. Following a brief pause, Violin 1 resumes its chromatic line, this time in an ascending direction, featuring a melodic inversion of Motive X. Caplin (1998, 176) labels these two halting phrase members as a basic idea followed by its varied repetition (thus expressing presentation function), but the phrase’s omnipresent chromaticism and fragmentation argue against this interpretation. Due to the liquidation of its motivic material, the phrase reaches a point of near-stasis, as if unsure where to go next. The subordinate theme resumes its motion with apparent difficulty in measure 88. Violin 1 and cello lead in parallel tenths, with Violin 2 and viola replying in a brief imitative passage. A deceptive resolution in measure 90, enhanced by a triple suspension, marks a further pause in the action, before a trio of staccato chords (recalling measures 7–8) ushers in a PAC, whose goal chord elides with the subsequent closing material. As Caplin (1998, 175) observes, Haydn had used a dominant triad in measure 8, allowing an interpretation of a HC as the phrase’s harmonic goal. Here, the concluding chord is a V7, thus the penultimate chord of a cadential progression. The unison B in the lower register completes the harmonic motion to tonic harmony in measure 92, though the registral displacement makes this tonic arrival less than convincing as the movement’s ESC—the movement’s harmonic completion will be accomplished in the following phrases.

Measures 92–108 tie up the movement’s remaining musical loose ends (Example 5). Subordinate Theme 2 begins with a presentation phrase featuring the main theme’s opening incipit, stated in unison to resemble measures 9–10. The late reprise of this striking musical segment compensates for its omission from the Main Theme plus Transition module earlier in the recapitulation. Rather than initiating transition material as it had in the exposition, this material now ushers in a second subordinate theme—one that is more regular in design than the preceding material, as Caplin (1998, 175) remarks. Though this musical content is familiar from its appearance midway through the exposition, Haydn puts it to significantly different use in the recapitulation.

The tonality-defining character of this phrase—a compound basic idea comprising a three-measure basic idea and a three-measure contrasting idea—is apparent: Haydn alternates tonic and dominant for six measures. Nevertheless, a rapid upward expansion of register in Violin 1, along with jagged arpeggios in the lower three voices, maintain an unsettled emotional state despite the straightforward harmonic design. A continuation⇒cadential phrase elides with this segment in measure 97, creating a stark change in character from the preceding material while maintaining musical tension. Following a descending scalar link, Haydn restates the ascending leap gesture of measures 28–30, intensifying it to an extreme that is unusually bold for 1790. First presented as ascending sixths in the exposition and already expanded to ascending octaves in the development, the leaps now span two octaves in Violin 1, further emphasized by biting sforzandi, while the remaining instruments provide chromatic support. A Neapolitan sixth, followed by a secondary diminished seventh chord (both marked sforzando) leads to the similarly emphatic cadential six-four of measure 100 and its resolution through V7 to a forceful PAC, the ESC of this recapitulation.

The closing section follows in measure 102. Cast in B minor, this passage lacks the alternating pizzicato and arco that had characterized it in the exposition. There were no open strings available to emphasize the home key’s tonic and dominant as had been the case in the exposition; consequently, Haydn wisely omits this coloristic device for ease of performance. As the final phrase unfolds, the Violin 1 melody soars upward in a brilliant passage once again permitting virtuosic display for Tost, ultimately reaching a dizzying B6 far above the treble staff at the concluding PAC. With this unusually high note resounding in our ears, this rich and formally complex movement reaches its conclusion.

Conclusion

Although Caplin’s detailed analysis of the opening movement from op. 64, no. 2 in Classical Form—to which both Langlois and Hall are clearly indebted—is an excellent beginning in accounting for its formal design, it falls short of solving all of the problems of this formally challenging movement. The main theme’s unusual “antecedent-antecedent” design and the subordinate theme’s onset remain particularly problematic according to the principles of Caplin’s theory of formal functions. Furthermore, the recapitulation’s reordering of the exposition’s thematic content and phrase structure further complicates the task of establishing a definitive formal reading.

As this study has sought to demonstrate, many of these difficulties can be resolved by incorporating the analytical frameworks of other authors to supplement Caplin’s theory. The main theme’s unusual cadential design can be reconciled with Caplinian form-functional thought if measures 1–8 are interpreted as the first half of a longer formal unit: Main Theme plus Transition. If so understood, this formal region, which would be anomalous at the eight-measure level as an independent theme, becomes normative at a deeper level of structure. Later in the exposition, the transition-subordinate theme boundary is problematic only if one follows Caplin’s lead in insisting that the transition must end with a HC. However, if one admits the possibility of a PAC as medial caesura, as Hepokoski and Darcy do, a far more convincing candidate for the transition’s concluding cadence (and therefore the exposition’s medial caesura) arises: the definitive, rhetorically marked PAC of measure 20.

The greater flexibility that arises from combining different analytical approaches helps guide us through Haydn’s complex recapitulation. Despite its reordering of thematic materials, the recapitulation’s formal trajectory follows the same path as the exposition. A blended Main Theme plus Transition formal region, pruned from 20 measures to 10, leads to a PAC, followed by a subordinate theme area featuring unexpected tonal excursions.

The musical challenges of this movement for analyst and listener alike might account for this work’s relative neglect compared to its five companion works from op. 64. Donald Francis Tovey’s remark (Tovey 1949, 62, cited in Langlois 2010, 119) that the quartet is a “great work, unduly neglected,” still seems accurate. Charles Rosen’s discussion of these works in The Classical Style is instructive, and typical of the music field’s appraisal in general: Rosen cites op. 64, no. 1 and nos. 3–6 multiple times, often at length, but comments on op. 64, no. 2 only briefly (Rosen 1997, 140) in reference to its affinity with the ambiguous tonal opening of op. 33, no. 1, an observation that dates back at least to Tovey.

Notwithstanding this relative neglect, op. 64, no. 2 warrants careful attention. The opening movement’s challenging formal layout displays Haydn’s uncanny knack for deconstructing sonata-form procedures. Building upon Caplin’s analysis (and the closely related ones by Langlois and Hall), leavened with Schmalfeldt’s “form as process” and Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory, this essay sought to explain this movement’s often enigmatic formal journey. A definitive interpretation of this movement stretches the capabilities of any single analytic method. However, intermingling analytical concepts from multiple authors provides a clearer picture of this fascinating movement, giving us a new appreciation for the richness of Haydn’s compositional technique.

References

Barrett-Ayres, Reginald. 1974. Joseph Haydn and the String Quartet. New York: Schirmer Books.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 2014. “The Half Cadence and Other Such Slippery Events.” Music Theory Spectrum 36: 203–227.

Caplin, William. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

⸻. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.”

Journal of the American Musicological Society 57/1: 51-118.

Fillion, Michelle. 1981. “Sonata-Exposition Procedures in Haydn’s Keyboard Sonatas.” In Haydn Studies: Proceedings of the International Haydn Conference. Washington, D.C. 1975. Edited by Jens Peter Larsen, Howard Serwer and James Webster (New York: W. W. Norton): 475–481.

Green, Douglass 1979. Form in Tonal Music: An Introduction to Analysis. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Graue, Jerald C. 2013. “Sonata Form Problems by Jens Peter Larsen (1963), translated by Jerald C. Graue (1978).” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 2, no. 2: Article 16.

Hall, Matthew. 2019. “Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9, no. 1: Article 2.

Haydn, Joseph. 2008. Streichquartette Opus 64. Edited Georg Feder, Isidor Saslav, and Warren Kirkendale. Munich: G. Henle Verlag.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keller, Hans. 1986. The Great Haydn Quartets. New York: George Braziller.

Langlois, Mathieu. 2014. “Haydn’s ‘Irregularities’: Ambiguous Openings in the B-minor String Quartets, op. 33/1 and op. 64/2.” In SECM in Brooklyn 2010: Topics in Eighteenth-Century Music I. Edited by Margaret R. Butler and Janet K. Page (Ann Arbor: Steglein Publishing): 103–130.

Landon, H. C. R. 1978. Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Volume 2. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press.

Ludwig, Alexander. 2010. “Three-Part Expositions in the String Quartets of Joseph Haydn.” Ph. D. dissertation, Brandeis University.

———. 2012. “Hepokoski and Darcy’s Haydn.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 2, no. 2: Article 5.

———. 2013. “Expecting the Unexpected: Haydn’s Three-Part Expositions.” In Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d’étude du dix-huitième siècle 31: 32–40.

Rosen, Charles. 1988. Sonata Forms. Revised Edition. New York: Norton.

———. 1997. The Classical Style. Expanded Edition. New York: Norton.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. “Form as the Process of Becoming: The Beethoven-Hegelian Tradition and the ‘Tempest’ Sonata.” Beethoven Forum 4 (1995): 37–71.

———. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tovey, Donald Francis. 1949. “Haydn’s Chamber Music.” In The Main Stream of Music and Other Essays (New York: Oxford University Press): 1–64.

Notes

- Landon 1978, vol. 2, 657; Rosen 1997, 140; and Langlois 2010, 119.

- As Rosen (1988, 1) asserts, “statement-counterstatement” is the nineteenth century terminology for a main theme followed by a transition that begins with a main theme incipit. Douglass Green (1979, 192–193) describes such a transition as “dependent.”

- Since, by definition, a presentation phrase does not end with a cadence (Caplin 1998, 10), the apparent HC of measure 8 (as well as measure 4) would be of “limited scope,” following Caplin 2004, 86–89.

- The MC is a rhetorical pause at the transition’s conclusion that opens up space for a subordinate theme (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 24–40).

- Hall (2019, 20) suggests a third possibility for the MC: the arrival on V of D major midway through measure 16. This location for the MC is less convincing than the other two since it occurs in the middle of a phrase. Furthermore, the two repetitions of Motive X form the presentation phrase of a loosely constructed sentence—another reason Caplin (1998) chooses to begin the subordinate theme area here instead of in m. 20 (see his discussion on 114–115).

- Langlois writes that measures 15–20 are “harmonically consequent to the previous phrase [which]…has the aesthetic effect of continuing melodic instability,” implying that these measures complete the formal process begun in measure 9 (Langlois 2010, 123).

- Essential expositional closure (EEC) demarcates the subordinate theme from the closing material that follows (Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 120–124).

- Caplin 1998, 116, Example 8.15.

- A “purple patch,” analogous to “purple prose” in literature, is Tovey’s term for an unexpected tonal excursion (Tovey 1949, 41–42). Ludwig (2013, 31–32) demonstrates the frequent use of “purple patches” in Haydn’s subordinate theme groups.

- Caplin (1998, 45–47, 61) defines continuation⇒cadential function as a closing unit in which a theme’s continuation segment can in retrospect be analyzed as the beginning of an expanded cadential phrase. Caplin (1998, 265, n.46) acknowledges a debt to Schmalfeldt for this concept of retrospective formal interpretation, first presented in Schmalfeldt 1995.

- Caplin nonetheless proposes a perfectly reasonable chord-by-chord harmonic analysis of these measures (1998, 104, Example 8.6).

- See also Fillion 1981, 478–479. Ludwig 2010, 2012, and 2013 further explore the prevalence of the three-part exposition in Haydn’s use of sonata form.

- Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 217–219) describes a few different rotational types within the developmental space.

- This strategy differs from the “Pre-core/core technique” that typifies development sections of Mozart and Beethoven (Caplin 1998, 141–155).

- Following Caplin (1998, 157–159), this analysis considers the modulatory phrase that leads to the development’s concluding dominant pedal to be the retransition, rather than the dominant pedal itself. This analysis is particularly satisfactory in developments such as this one, where the dominant arrival is brief.

- Along these lines, Landon alludes to a recapitulation (Symphony no. 45, I) in which “Haydn simply goes on developing” (1978, 302).

- Subdominant emphasis is a common feature of a “secondary development,” discussed in Rosen (1988, 289–296).