Issue No. 11: October, 2000

Publisher’s Notes by Paul R. Judy

Field Activities and Research

The Oregon Symphony: A Journey of Transformation by Elaine Cogan

Healing the Starfish by Saul Eisen

Oregon Symphony Strategic Plan: A Consultant’s Perspective by Elaine Cogan

Hartford Symphony Orchestra : A Work in Progress

Cultural Change in the Pittsburgh Symphony Organization

The Problem Solvers: Orchestra Personnel Managers

Reflections by Paul R. Judy

About the Cover…by Phillip Huscher

Wither the Audience for Classical Music? by Douglas Dempster

Symphony Orchestra Organizations in the 21st Century

Full Report: Orchestras in the 21st Century

If queried, most participants in symphony organizations would probably say that there is an intensive amount of communication and face-to-face contact which goes on in this business, and would cite personal experiences. During a season, many members of boards, staffs, orchestras, and volunteer groups spend countless hours in meetings and related discussions. Board members and other volunteers lament the time they spend in symphony meetings. Orchestra committee members complain that they seem to be in a continuous session. Externally, executive directors and other staff members, and volunteer leaders, attend various conferences and meetings where information is shared and gathered, relationships are developed, and opinions and insights exchanged. Orchestras send delegates to annual conferences and other meetings to foster face-to-face contact with colleagues in other orchestras. Personnel managers and librarians have annual meetings to share professional insights and to give and receive mutual support. Year in and year out, in hundreds of North American symphony organizations, an enormous amount of time and energy is devoted by participants to gathering, getting to know each other, exchanging ideas through talking and listening, and carrying out business.

And so, during the course of a year, across the industry, what is the amount, regularity, and quality of verbal communication and relationship building which takes place within symphony organizations involving all the constituencies, and especially between all the persons elected and appointed to leadership roles within these constituencies? How much time and effort is devoted to having people in these groups get to know each other better through regular, authentic, and purposeful discussion? How much time and emotion is devoted to having constituency leaders explore where everyone is coming from and develop, as a team, where everyone needs to go, together, if the enterprise is to be successful? Teamwork involves practice, predictable and reliable actions, and thus trust. Shared experiences, stories, smiles, humor, and mutual support, are part of excellent teamwork. Creating these conditions takes time, energy, and true engagement. How many symphony organizations devote the necessary resources to these communications and relationships? Most readers would probably say, “Well, not too much of that kind of communications and relationship building is taking place in the symphony industry . . . but probably it should.”

There are some symphony organizations in which the steady and comprehensive development of communications and relationships throughout the organization is, in fact, a high priority, and is commanding a heavy investment of time and energy. Such efforts are leading to positive cultural change within these organizations. In the first part of this issue, we are pleased to tell or update the stories of three such organizations.

◆ Over the past three years, the Oregon Symphony Orchestra organization has embarked on an exciting transformational journey, as enthusiastically described by Joël Belgique, Fred Sautter, Lynn Loacker, and Tony Woodcock, beginning on page 1. Organizational development consultants Saul Eisen and Elaine Cogan, who have worked with the Oregon Symphony, add their perspectives on the organization’s growth. Given the well-publicized difficulties this organization was having, the change in this organization’s ecology is phenomenal. As the participants report, there is more progress to achieve, and gains to sustain. But the Oregon story shows what can be accomplished through commitment and teamwork of joint-constituency participants and leaders. Hats off to Oregon!

◆ The Hartford Symphony Orchestra organization realized a major catharsis in its organizational life through a contract renewal process carried out in 1994. The elements and stages of this process were reported in Harmony #5 (October 1997), by a roundtable of participants who were involved. We thought it would be interesting to check back with some of these participants, joined by some current constituency leaders, to see how things were progressing in the Hartford organization. “Quite well, but with continuing challenges” is the answer you will hear from Ann Drinan, Dwight Johnson, Candy Lammers, Arthur Masi, Millard Pryor, Greig Shearer, and Tom Wildman, as reported on page 16.

◆ The institution which is perhaps leading the pack in innovative organization change—at least among the larger orchestral organiza- tions—is the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra organization. As described in Harmony #7 (October 1998), the PSO began, in 1997, to employ Hoshin, a unique strategic planning technique of Japanese origin. This initial experience soon led to the expanded use of Hoshin. With further experience and practice, the PSO has begun to employ, increasingly throughout its operation, the principles which underlie the Hoshin technique, and some other similar techniques, in such a way that these tenets are now becoming a dynamic part of a new culture developing in the PSO organization. The sense of sustained if not accelerating change taking place in this organization comes through rather clearly in the voices of Scott Dickson, Hampton Mallory, Ron Schneider, Linda Sparrow, Bob Stearns, Kathy Kahn Stept, Tom Todd, Gideon Toeplitz, and Rudolph Weingartner, which are recorded starting on page 24.

On behalf of the Institute and Harmony’s readers, we thank all of the participants for the concern and time they gave to these three roundtable discussions in order to better inform others throughout the symphony world about what high- level, interconstituency communication and involvement can do for organizational vitality and participant satisfaction.

Bridging, then squeezing down, and finally eliminating the space between the constituencies of a symphony organization is not easy, and is a process to which too few symphony organizations are seriously committed. The gaps between orchestra and staff, and between orchestra and board, are the widest and most boundaried in most symphony organizations. As I pointed out in my earliest essay in Harmony #1, the separateness of the orchestra from its supporting elements—staff, board, and volunteers—has its roots in the very nature of the art form and its historical development. In this regard, this tendency toward separateness might be considered “natural,” therefore requiring rather unique and creative organizational efforts and structures, if it is to be bridged and overcome. In more than 100 North American organizations this separateness is heightened by an orchestral collective bargaining agreement. In helping to bridge both the natural and the manmade boundaries between these two worlds, and in administering a document which attempts to link them, orchestra organizations have come to depend on the personnel manager, a special role within symphony organizations. Thanks go to Doug Hall, Llew Humphreys, Jeff Neville, Greg Quick, Carl Scheibler, Linda Unkefer, and Russell Williamson for informing Harmony’s readers about this position and some of the duties and ambiguities their work entails.

After participating in or reviewing these four diverse roundtable discussions, I found myself reflecting on the long journey ahead for organizations which do not aspire to become truly unified communities, and the need to get on with this effort (page 37).

On page 43, we turn to a topic of keen interest to everyone interested in the future development of symphony organizations. Is the audience for classical music shrinking, or, in fact, growing? Are the doom-and-gloom pessimists or the naive optimists right? Not persuaded by the anecdotal sentiments of either camp, Douglas Dempster, Dean of Academic Affairs at the Eastman School of Music, has taken a hard look at the numbers. His conclusion is that growth, not decline, has been taking place. Doug is also the director of Eastman’s Catherine Filene Shouse Arts Leadership Program, dedicated to more completely preparing students for the real world of the professional musician.

We are pleased once again to bring to our readers’ attention the perceptive writings of Christos Hatzis. As is noted on page 56, we have excerpted some key points made in a recent Hatzis essay which is posted on his Web site, and thus are initiating a linkage between the pages of Harmony and content increasingly appearing on the World Wide Web.

In a further step in initiating a link between content appearing in Harmony and that posted on our own Web site, <www.soi.org>, we are pleased to present a report looking to the symphony organization of the 21st century. On page 59, we introduce readers to the main points in this report, which is an amalgam of the contributions of 13 current and former members of the Institute’s Board of Advisors. On our Web site, readers will find a complete presentation of the report, which can be easily downloaded and printed for even more careful study, which we hope many readers will wish to do. We believe this report will be especially useful to those involved in symphony organization strategic planning or otherwise interested in the future of symphony organizations. Interspersed with the Harmony presentation are various quotations relating to the future environment for symphony organizations.

On page ix, under The Institute, the Internet, and the World Wide Web, we describe various matters which relate to the Institute’s own future development.

◆ If you are a symphony organization participant, we hope you will take a few moments right now to complete and return (in the postage prepaid envelope) the survey packaged with your copy of Harmony. We need your response to better serve you and your organization over coming years. By providing us your e-mail address, you become eligible for a handsome prize. Act now!

◆ We go on to outline our plans to publish Harmony content increasingly on a dual basis—in the traditional paper printed and mailed form, and also the newer electronic form available for reading, downloading, and printing. Over the longer term, we can envision our Web site becoming an electronic forum for information, discussion, education, and interactivity regarding symphony organizational issues—well beyond the potentials of a periodic print publication.

◆ We reiterate the service orientation of the Institute toward symphony organizations which are committed to its aims and efforts, and which signify that commitment by an annual voluntary contribution. More about this continuing focus during 2001 can be found under Distribution of Harmony and Institute Support, on page 73.

◆ We also announce the formation of the Advocates of Change, reported in more detail on page xiii. This is an association of participants and supporters who believe that symphony organizations must become more effective and high performing, and will only become so if more participants begin to push new approaches. Some 35 people from around North America have coalesced as founders of this group.

Recent developments in the Institute’s field activities are reported on page xii. Although the reports are brief, the significance of these activities is large. Some day, out of the Institute’s field efforts, and also drawing on the experience being gained in other cities and organizations—be it in Pittsburgh, Portland, Hartford, New Orleans, or elsewhere—I am hopeful that the Institute will be able to bring about a broader understanding of the beliefs, principles, processes, and methodologies that can underpin real transformational change in North American symphony organizations and throughout the field at large. In the meantime, we will continue to work quietly with selected organizations and groups in these efforts to perfect insights and designs. Finally, as noted, the Conductor Evaluation Data Analysis research project has been further delayed, but hopefully will be completed in 2001.

While speaking of commitment to organizational change and improvement, we are very pleased to note that the Institute ended 2000 with some 158 supporting symphony organizations, a new record, including 18 organizations which provided their support for the first time (page xv).

Following past policy, on page 71, we report the Institute’s financial operations for the year ended March 31, 2000, and our financial condition as of that date.

Lastly, we are indebted to Phillip Huscher for the musical score fragment appearing on our 11th cover and the snippet of orchestral history it symbolizes. Can you diagnose the music? Do you wish to conjecture as to the historical development to which it refers? If you get this one, you are a magician or a genius! See page 39.

All for now. Good reading!!

Field Activities

Through its representatives, the Institute is continuing to work jointly with participants of the Philadelphia Orchestra organization in an ongoing, multi- year organizational improvement program which is showing steady progress.

In the spring of this year, the Institute was invited by the various constituencies of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra to join them in a concerted effort to become an outstanding organization, with very challenging short- and longer-term goals toward that end. Major accomplishments have already been achieved in a very short time frame.

In August, Institute Board members Fred Zenone and Paul Boulian were invited to attend the annual meetings of ICSOM and ROPA, player conferences within the American Federation of Musicians. At the ROPA conference they led a discussion of the paradoxes and challenges faced by ROPA orchestras. At the ICSOM conference, they were asked to stimulate a discussion of the role of ICSOM in addressing the issues faced by orchestras in that conference. This discussion, lasting more than three hours, encouraged an expression of the diversity of views that exist within the conference.

Research

The Institute has been delayed in its effort to complete the Conductor Evaluation Data Analysis project. Factoral data for a number of conductors and orchestras in the data universe have been compiled, but completing the programs through which these factors can be integrated with database information and the results correlated and analyzed, has taken more time than earlier contemplated. Thus, it is now expected that this research project will not be completed until some time in 2001.

The Oregon Symphony:

A Journey of Transformation

A roundtable discussion

F or the Oregon Symphony, the 1980s and early 1990s were years of change. In the early 1980s, the symphony became a full-time orchestra, making it the primary occupation for its musicians. Not many years thereafter,

deficits began to build and relationships began to sour. One manager moved on, a board member served as manager for more than a year, and during a third manager’s first contract negotiations, the orchestra was locked out. Could things possibly get worse? Unfortunately, the answer was yes. However, in 1997, the Oregon Symphony began a journey of transformation.

In February 2000, Fred Zenone, vice chairman of the Symphony Orchestra Institute, paid a visit to the Oregon Symphony. He had followed the events of the difficult years and was pleasantly surprised by what he found in Portland. He invited four members of the orchestra family to participate in a roundtable to discuss where they had been, where they are now, and where they are going. At this point, we will let them pick up their story.

Institute: Let’s begin by asking you to introduce yourselves and telling our readers about your involvement with the Oregon Symphony.

Joël Belgique: I became principal violist with the orchestra in January 1997. I chair the orchestra committee, although my term ends as the new season begins. I also teach at Portland State University and Lewis and Clark College and am active in chamber music performance.

Lynn Loacker: I currently chair the board of directors for the Oregon Symphony. I became board chair in 1997 and have served on the board for 10 years. I also serve on the board of the Oregon Symphony Foundation.

Fred Sautter: I’m principal trumpet, an ICSOM delegate, and have served on the negotiation teams in 1996 and 2000. I’ve been with the Portland Symphony for 32 years which makes me the resident historian for this roundtable.

Tony Woodcock: I became president of the Oregon Symphony in December 1998. Prior to that I was managing director of the Bournemouth Orchestras in Great Britain for eight years. I am a violinist and have spent 25 years in arts management.

Institute: The year 1996 was a particularly difficult one for the Oregon Symphony. Fred and Lynn, you were involved with the orchestra at that time. Explain to our readers what happened.

Sautter: Following the lockout, we got yet another new manager and things seemed to be going well for a while. However, you need to understand that there was still a good deal of distrust because of the lockout. As time progressed, the grievances began to mount and that brought us to the negotiations of 1996. On the surface, it appeared that everything was rosy with increased ticket sales and so on, but what we actually had was a dysfunctional relationship between management and musicians. The bottom line was that the musicians went on strike.

Loacker: I was on the executive committee of the board at the time and I still didn’t feel that I had all of the information that I needed. And certainly none of the background that I needed to make some of the decisions we were being asked to make. I remember thinking, “The musicians are trying to get blood out of a turnip. Why don’t they understand this?” Well the reason they didn’t understand it was that there had been no honest communication about what the finances really were. And even if there had been information sharing, no one would have trusted the information because management, at that time, was very selective in what information was shared. The strike was a wakeup call. And although some people say it was a horrible thing for us to have gone through, to me it was a necessary evil. It was a turning point because we clearly could not continue to do business as usual. Very shortly thereafter, I became board chair.

Institute: What thoughts were on your mind as you stepped into that role?

Loacker: When the strike ended, I thought everything was going to be just fine. But then several members of the staff left the organization. And I thought, “Maybe this won’t be quite such a walk in the park.” But my main hope and goal was to improve communications among all of the constituencies.

Woodcock: What Lynn brought to the organization was intuition, personality, and style. I don’t think she needs to think about these things. She just does them.

Loacker: I was determined to improve communications and began by just talking and listening to people. I had many conversations with musicians and I was much more hands-on in day-to-day situations around the office. We had had corporate people as board chairs for a very long time. So, of course it was going to be different because I don’t have a corporate background and wasn’t coming from that angle.

Institute: And then, Tony, you joined the organization shortly after Lynn became board chair?

Woodcock: I characterize it that I came in on the surf of what Lynn was creating. Lynn started in 1997 and I began in December of 1998. One of the first positive things that happened was the search process itself for my position. The orchestra was consulted and was asked to nominate two members of the search committee. From my side of the table as I was being interviewed, I felt that this was building bridges.

Loacker: We had representation from all of the “arms” of the organization. Through our process, we came up with a common view of what qualities our new president needed to have. The whole group wrote out words that would characterize the type of person we needed. But the important point is that we made sure that everybody who needed to be at the table was there.

Belgique: I started here in January 1997, after being a member of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra for three and a half years. And I would have to agree that there was a lot of distrust when I first came. Not just between the musicians and management, but among the musicians themselves. At the time, I found it surprising that some of my colleagues had not spoken to each other for years. The search for a new executive director was a perfect opportunity to do things differently. When the search committee was down to three final candidates, a group of six musicians, who had been chosen using a sign-up, was asked to meet with the candidates over lunch. The search committee took our input and opinions seriously and, ultimately, the selection was the musicians’ choice. This group of musicians, as well as the rest of our colleagues, felt that this process was a positive one.

Sautter: The important point here is that the musicians—not just the musicians who were directly involved, but the orchestra at large—knew that we were involved in the decision-making process. This was very important in developing the air of openness that we now have.

Institute: Tony, were there any thoughts that you brought out of a different organizational culture in England that helped the Oregon Symphony address their issues?

Sautter: Tony is far too modest to answer that question. You need to understand that this orchestra had not only come to the point that people were not speaking to each other, there was actually sabotage going on among the musicians. We desperately needed someone of dignity, of patience, someone with knowledge of and experience in our business. In other words, a complete human being.

Loacker: Tony listened. In the beginning, he had numerous meetings individually with the musicians. He shared information and was available to listen and to answer questions. Tony builds trust by sharing information, by being consistent, open, and honest.

Institute: As we understand it, there then came to be more formal groups. The 2000 Plus Committee. The Collaborative Task Force. A group that worked on the Strategic Plan. Tell us about those.

Loacker: The 2000 Plus Committee and the Collaborative Task Force were already meeting in 1997. The 2000 Plus Committee actually came out of a grant we received from the Knight Foundation’s Magic of Music initiative, and included having one of their consultants, Bill Keans, work with us to see if we could get a group together and actually begin to communicate. Board members, staff, musicians, and conductors had the opportunity to sit at a roundtable with no agenda, and no project to accomplish. And Bill helped us to understand that there were many layers that had built up and that we needed to “peel away the onion,” as he described it. That was the beginning of our learning to communicate more effectively. The Collaborative Task Force was another small group of board members, musicians, and staff formed to address our financial picture in 1997.

Sautter: And then, with the help of the Symphony Orchestra Institute, Saul Eisen came in as a scholar in residence and helped us explore our issues and communication or lack thereof.

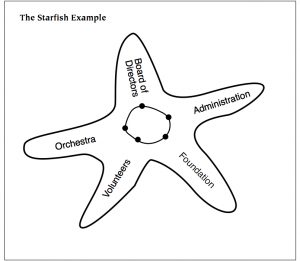

Loacker: Saul did a residency in which he visited us for two days each month for six months. Although he was technically here as an observer, he spoke with everybody. This was another opportunity for many of us to vent and begin to address some of the issues. And he left us with a “starfish” metaphor that we are still using.

Institute: Explain the metaphor for our readers.

Loacker: The idea is that the organization can be likened to a starfish, with each arm representing one of our five constituencies. Scientists have studied the function of the ring of five interconnected nodes near the center of a starfish. When the nerve ring is intact, and all five arms communicate, the starfish can decide to move in one direction or another. When the central nerve ring is severed, the arms react independently to multiple stimuli, and the starfish tears itself apart. That’s a pretty vivid reminder that has stuck with a lot of people. It is very helpful to understanding the need for a core of communication and how important it is for everybody to be on the same page.

Sautter: Saul was very easy to talk to, was a great listener, and knew what questions to ask. And I think the study took place at a crucial time for our benefit. We needed some guidance as to what to do and how to do it. The starfish metaphor really is vivid for us. If the five segments of this organization are not communicating around the outside of the circle, then trouble begins. This is almost a complete turnaround from where we were.

Institute: We also understand that you have developed an 83-page strategic plan which must have been an enormous amount of work. How did that come about and who was involved?

Woodcock: It arose from need. Lynn has mentioned the need for communication. And out of our need for communication came a need for knowing where we were going. As an organization, we needed to be on the same page. Now, I could have sat in my office over a weekend and written it and then showed it to everyone. But that would have been my report and my strategy. And no one at all would have signed up to it. It wouldn’t have taken long to write, but we would have spent months and months fighting, and persuading, and cajoling.

Instead, we went into a very detailed, arduous process which was meant to bring together the five arms of the organization, so that when a final strategy was produced it would be as a result of everyone’s input. And everyone would buy into it for the future. I describe it that we had to go slow in order to go fast.

We involved a consultant, Elaine Cogan, who is well known in Portland. She talked about a process that should involve everyone and suggested that as part of the process we should have a minimum of two family days where everyone would get together to discuss ideas. And that is exactly what we did.

At the beginning of the process, we had a family day at a hotel and 112 people attended. At the second family day, which concluded the process, well over 140 people attended. Those were full-day meetings. Everyone was there. The musicians were there. The staff was there. The board was there. The volunteers were there. The conductors came along and it was very, very positive for the organization.

The strategic plan, all 83 pages of it, was ratified last November 16. And everyone has a copy. We use it not only for direction. We use it to raise money. We use it to sustain relationships in the community. We use it for really positive messages. The steering committee that took us through the whole of this was representative of all of our constituencies, and from small beginnings that idea of inclusion has permeated our whole organization in a very strong way.

Sautter: Let me speak from a musician’s perspective. Through this process I met all kinds of people who had been around the orchestra for years but whom I did not know. I made some very good friends. A woman who is a judge here in Portland, and whom I have admired for my entire tenure here, has become a dear friend. We saw each other’s sweat for so long that we got to know each other really well. This process allowed us to be candid at a level I would have never expected. When we had problems we couldn’t solve in a large committee— which can be cumbersome—we formed subcommittees or small task forces to deal with them. We shared sweat and toil to come up with solutions. In each and every case, our solutions included the collaboration of all of the parties involved.

Institute: Joël, you are relatively new to the orchestra, but you must have been orchestra committee chair through part of the process that resulted in the strategic plan. What role did the orchestra committee play?

Belgique: We were very involved from the beginning. We were involved in everything from choosing a consultant to reviewing the final draft. But I think that the main job of the orchestra committee was to make sure that the rest of the orchestra had a good idea of what was going on. We wanted to excite the musicians into taking part, into taking ownership, and into the whole plan itself. I think I speak for most of my colleagues when I say that the strategic plan is a working document and is not a dust-gathering piece of paper. Each element has a thesis statement which defines the goal, followed by a statement of strategy. It then lists the persons or groups responsible for seeing the element through, including timelines for review and evaluation.

I think the role of the committee has evolved as a result of this process. People who hadn’t been the best of friends were finding the energy to talk with each other. We organized an ad hoc committee of musicians representing all corners of orchestral politics simply to elicit dialog and bring people to a better understanding of one another’s views. The musicians were included in Tony’s hiring, we were included in the hiring of a general manager, and we are very much part of the music director search. All of these actions have helped to affirm that we are part of the organization. And I would add that many of the younger players who were hired in the last three or four years have assumed committee responsibilities, and so have some musicians who had said that they would never serve again. They are coming back and participating.

Institute: Lynn, what effect did this process have on the board?

Loacker: At the time we began the strategic planning process, our board had nearly 50 members. As is usually true with a large board, a small group ends up doing a lot of the work. But board members wanted to be part of the process, especially the family days. Members of the foundation board were also involved. As Tony has related, the family days were very successful. It was fun to hear board members say that they had learned from the musicians, or from the telemarketers. We all had a deeper understanding and appreciation of what was going on in the organization and of each other’s roles.

Institute: In reviewing the strategic plan, it appears that there are to be changes in board structure. Would someone explain those?

Loacker: We’ve adopted a new board structure that will have a larger executive committee which will be involved in more of the day-to-day operations, and a group of community members who will be involved on a variety of committees.

Woodcock: It is the plan that musicians will have two places on the executive committee.

Sautter: We are in contract talks right now—I’m on the negotiating team—and we’ve discussed this. It is my belief that this will be acceptable to the musicians.

Woodcock: Having musicians on the board is a continuation of the commitment to open communications, to an open decision-making process. It is one thing to be observers, which the musicians are now, but to be voting members of the executive committee is a very deep manifestation of trust.

Institute: The Oregon Symphony currently has a search under way for a music director. It is our understanding that you are following an unusual process. Can you explain that to our readers?

Woodcock: When I came into the organization and began to get to know the orchestra as individuals, I very consciously decided that the musicians had to be the majority shareholders of the search process. So the music director search committee involves seven musicians, which is a majority. Some of my distinguished colleagues from other orchestras think that I am mad to do it this way. But I feel that it is very appropriate to our future here in Oregon.

When we opened the process, anyone could nominate a candidate. At our first meeting, we were faced with a list of 72 conductors. The search committee, particularly the musicians, have worked very hard to sift through those names to learn a great deal about these conductors. It has been a fabulous process. We now have a short list of 12 known applicants. The first six will come through this season, and six more will appear next season. And then they will come back again in years three and four. This process has galvanized the orchestra.

Loacker: As a board member, it had always been my perception that a music director search happens very quickly, that it is a mad dash to fill the position. And I am sure there are other board members out there who have that perception.

Belgique: Musicians have very strong opinions about who is on the podium. We play differently for different people. Musicians may not know as much about the marketing potential of a potential music director as board or staff members might, but I am convinced that if we have a conductor who excites and inspires the musicians, the result will be demonstrated in the way we perform, which, in turn, will bring more people into the house.

I also want to mention that the search committee agreed that we would not let the conductor just choose the programming. We did not want conductors to come in and do only what they do best. Each has been asked to submit choices from which the search committee will make a selection, and each has also been asked to conduct a classical-period concerto.

Institute: Lynn, does this search process make sense to you as a board member?

Loacker: With the exception of perhaps one or two people, our board members had not been through a conductor search, didn’t have a clue as to what the process should be, and were open to Tony’s suggestions. Initially, some of us wondered about why we were going to take five years. But the explanations made sense. It is understandable that a conductor can be on his or her best behavior for one performance, and that we need to see our candidates in a variety of situations. We also recognize that we cannot just ignore our current conducting staff and give the entire season to guest conductors. And we certainly understand why the musicians have a large vested interest in the outcome.

Institute: We are approaching the end of our time together. Are there any other thoughts that you would like to add?

Sautter: Yes. I mentioned earlier that we are currently involved in contract negotiations. And we are doing Interest-Based Bargaining. We bring board, management, musicians, and the union into the same room together. This morning we tallied up that we have been together for between 200 and 250 hours of talking during this bargaining process. We know that IBB is a very slow process. But the direct result is that we are all talking together on the same plane, sharing all of the information. No one is in the dark. We are making decisions together.

As a musician who has been here 32 years, I can tell you that there is a sense of trust coming out of this process that will build the future that Tony has talked about. When we add to the mix the artistic vitality we hope to have, we can look forward to good health for this organization so we can be the best that we can be.

Loacker: We have come a long way, but I see so much potential for doing more in the future. A lot of that has to do with some of the things that we are discussing now in IBB. But it starts with communication, with trust. We are building toward an organization in which everybody can talk openly and honestly with one another about what is going on and what needs to be done. Those developing relationships are important not only internally, but also with the community. The community needs to see what a vital, important aspect of their lives we represent. If we bring to them health—in relationships as well as in finance— that is an important contribution.

Woodcock: I know that one of the Institute’s objectives is to share information with orchestras to see if what one orchestra does might be applicable to another. Let me relate two very positive experiences we have had as part of the IBB process. First, when we decided to share budget information, we, as management, took a very deep breath because it had never been done that way before. The musicians would receive any information for which they asked. We have honored that, and the musicians probably have more information than the finance committee. Through that sharing of information came understanding, followed by an acute awareness of where we are as an organization. I thought that was a terrific process.

Secondly, we involved Lynn, as our board chair, the chair of our foundation board, and the board member who chairs our liaison committee on the negotiating team. I think the success of our discussions has been largely due to their involvement. They have not said the wrong things. In fact, they have said the right things. They have challenged management as well. When the board members have felt that they did not have enough information, they have asked for it so they are better prepared for the next meeting.

I would encourage people to take that line for the future. Because it means that to the musicians, the board is no longer a “gray eminence” somewhere in the background. The musicians have a direct line to the board chair and other members of the board. Through this process of discussion, they can affect attitudes and can communicate at the level they desire.

Sautter: The only wrinkle that I would want to identify is to again mention the monumental time commitment. As the discussions have continued, there has been honor and respect, and we do formal updates when someone has been unavailable for a meeting. In the future, the time commitment may be less because the friendships we have formed will sustain us through separations, and will allow us to get back together more quickly because we have worked well together before. We still have a lot to fix, but we are well on our way and I feel very good about that.

Institute: What a positive note on which to end this conversation. We thank you very much for your time and know that the Oregon Symphony’s organizational development over the past three years will provide food for thought for many of our readers.

Healing the Starfish

W hen the Symphony Orchestra Institute invited me to participate in its Scholar in Residence program, I was both pleased and apprehen- sive. While I had three decades of experience as a professor of organizational behavior and as a consultant to a wide range of organizations, I had not worked with orchestra organizations and knew little about them. I sensed, too, that my presence and involvement as a learner would not be invisible, and would inevitably have some effect on the organization—hopefully a positive one.

In retrospect, the residency experience with the Oregon Symphony did give me a unique opportunity to learn about this organization, and to some extent, about orchestra organizations in general. There are some ways, too, in which I was able to serve as a sounding board for the individuals and groups I interviewed. I sensed as we talked that their experiences, perceptions, and assumptions were being amplified, reverberated, and made more available for reflection and self- awareness.

Tim Scott, who was then chair of the orchestra committee, was part of a group doing ongoing planning for my visits, and he arranged meetings with the committee he chaired. Fred Sautter was very helpful in arranging informal gatherings with musicians representing a range of views—including people who perhaps would otherwise not have agreed to talk with me at the time. I also simply sat in and observed a number of regular meetings.

Listening and Learning

When I observed group meetings, my approach was to attend to what each group was attempting to do and how it was doing it. I was openly curious about the task and function of each group, in the context of the larger organization. This is essentially a neutral stance—not particularly looking for problems to solve or improvements to suggest, but simply noting the group’s behavior as it is. Similarly, in talking with individuals I was interested in understanding their unique ways of perceiving and experiencing themselves and the organization.

I learned of the successful growth and development of the Oregon Symphony over the last two decades, under the visionary musical leadership of James De Preist and two other uniquely talented and energetic conductors—Norman Leyden and Murry Sidlin. The transition to new musical leadership, however, was not evident to me at the time.

I heard in great detail about a history of difficult experiences related to financial pressures, a painful strike, operational snafus, the limitations of the concert hall, and low morale among many members of the orchestra. As I talked with musicians, board members, managers and administrative staff, and volunteers, I became aware of a low level of trust between individuals and groups. I noticed, too, a number of ways in which distrustful assumptions and group stereotyping were leading to a high incidence of misunderstandings, which only fed the mistrust and stress people were experiencing.

I recognized this pattern as one that is endemic to other kinds of organizations—whether in the arts, service, manufacturing, or technology; I have certainly seen it before. Many organizations have functionally separate constituent groups, such as marketing, operations, and finance—or in this case, the orchestra, management and staff, the board of directors, and volunteer organizations.

There is a tendency for each group to develop its own subculture and shared assumptions. The other groups are seen as adversaries, their members are stereotyped, and their motives are suspect. They each have their own priorities and ways of working. They are often housed in separate buildings and may seldom work together or even see each other.

Under these conditions it is not unusual to develop patterns of adversarial distrust for the other groups. When people are caught in such patterns they tend to personalize the problem as being caused by the other side—as a group or as individuals. The underlying fragmenting structures, however, are not acknowledged or understood; they hear the notes but not the music.

The Vicious Circle

This kind of repetitive pattern can be understood as a vicious circle (or more technically, a regenerating feedback loop). A high-stress/high-pressure environment tends to breed incomplete or distorted communication. This leads to frequent misunderstandings, which feed mistrust, which in turn amplify the pressure and stress, and so on. People caught in such a vicious circle tend to feel trapped and hopeless. And indeed, if no change is introduced, things only get worse.

But there is a hopeful irony in discovering such feedback loops, because for the same reason that they work in one direction they can work in the opposite direction—toward improvement. For example, if new activities or structures provide opportunities for valid communication across groups, there can be more mutual understanding, which allows trust to build. This leads to reduced stress, which in turn reduces the tendency to miscommunicate and misunderstand, and so on.

The story of the starfish that Lynn Loacker describes was my attempt to explore with her, and then others at the Oregon Symphony, the possibility of shifting attention to the underlying patterns in their dilemma. It is a very dramatic metaphor in the sense that it describes a fundamentally self-destructive pattern. She and others resonated strongly to the starfish metaphor, to a large extent because it connected with and supported their own emerging awareness of the nature of the problem. Indeed, activities like the 2000 Plus Committee and the Collaborative Task Force were structured specifically to bring constituent groups together around shared values and goals. These seemed to me to be very positive and productive initiatives, attesting to Lynn Loacker’s perceptive leadership.

Similarly, the search for a new president was guided and informed by a participative process across constituent groups. The fortunate selection of Tony Woodcock for the position reflects the shared awareness of the importance of moving toward a style of management that supports healing of old wounds and collaborating across constituencies. Indeed, he provided the needed leadership in the strategic planning process that has developed a new sense of direction for the whole organization, and a framework for continuing monitoring and decision making over the critical next few years. Again, the fact that a strategic plan was developed not by a few managers in a board room, but through an open process that brought together all the constituencies in a large-group format is indicative of his competent and effective leadership away from fragmentation and toward integration.

The same can be said for the wise initiative to use Interest-Based Bargaining. Rather than waiting for contract talks to begin and to predictably deteriorate into adversarial polarization, IBB has provided a forum for cooperative problem- solving toward shared goals. The monumental time commitment involved has been an investment in mutual understanding and healing.

The transformative process is not over, though it has developed a significant momentum. Perhaps the starfish, with its healing nerve ring, is beginning to function and thrive as a whole organism.

Saul Eisen is a professor of psychology and director of the master’s program in organization development at Sonoma State University. His international consulting practice integrates planning, whole system redesign, and organization development. He holds an M.B.A. from U.C.L.A. and a Ph.D. in organizational behavior from Case- Western Reserve University.

Oregon Symphony Strategic Plan: A Consultant’s Perspective

In my 25 years as a strategic planning and communications consultant with nonprofit organizations, I have rarely been as gratified and exhilarated by a process, and a product, as I have been from my recent work with the Oregon Symphony.

When we began, the organization probably was as disparate as I have seen, with each segment going its separate way, intersecting with others only when necessary, and even then, reluctantly. The strategic planning process we developed could not have worked without the full cooperation and participation of all members of the symphony “family.” As musician Fred Sautter notes in the roundtable, this all takes hard work and a significant commitment of time. I think everyone was surprised at the level of both we obtained and sustained as the process unfolded.

There were several keys to success. A significant contributor was the Long Range Plan Steering Committee, comprised of 17 representatives from every facet of the symphony family: board, foundation, staff, volunteer associations, and musicians. Except for the artistic director, whose schedule did not allow him to attend any meetings, steering committee members were very conscientious in carrying out their commitments. After previously interviewing them and other key people in and outside the organization, I suggested a planning process that would consider all the most important issues that needed to be resolved.

At the first meeting of the steering committee, there was an obvious wariness and tension in the room. This was to be expected, as many of these people had never before sat down together. It also was obvious, however, that one matter united everyone, from the women’s association representative, who has been a volunteer for the symphony for more than 40 years, to the newest staff member who had been on the job only a few months: love of music and of the Oregon Symphony. From June to November 1999, the group met regularly and intensively. I facilitated many, sometimes heated, discussions, during which steering committee members crafted statements of mission and values, and finally, specific action plans that were then taken to the entire symphony family for modification and ratification.

Another key element of success was the leadership among all parts of the Oregon Symphony family. They not only dedicated themselves to the process, but enthusiastically spread the word to their constituents and elicited their support.

Symphony Family Meetings

Two other significant keys to success were the symphony family meetings, the first held midway through the planning process, and the second held toward the end of the process. True to the guiding principles for the process, as exemplified by the inclusive steering committee, everyone associated with the symphony was invited to two all-day sessions held in a local hotel. To nearly everyone’s surprise, more than 100 people attended each time. At each family meeting, participants were seated at round tables of 10, each having a predetermined complement of musicians, board members, staff, and volunteers. Once again, as with the steering committee, people were delighted to meet others whom they did not know, and all were united in a love of music and of the Oregon Symphony.

At the first family meeting, after a briefing about the process and the preliminary work of the steering committee, attendees, at their small tables, discussed these questions:

◆ In the best of all worlds, five years from now, describe the Oregon Symphony.

◆ What factors help or hinder us from reaching those ideals?

◆ How can we overcome our problems and make the most of our opportunities?

Each discussion was facilitated by a steering committee member. The many good ideas were then taken back to the committee for further refinement.

Several months later, at the second family meeting, attendance was even greater and more enthusiastic as the word had gotten around that this strategic planning process was really going somewhere and everyone’s opinion counted. At this all-day session, attendees were once again preassigned to tables to ensure variety, and this time, many greeted each other as old friends. They considered elements of the strategic plan proposed by the steering committee, with the assignment to review, delete, or add as they thought appropriate.

Moving Toward a Final Plan

The steering committee considered all these recommendations seriously and made modifications which were then considered at meetings of each group of family members (staff, musicians, volunteers, etc.) led by steering committee members. The final plan was once again revised and forwarded to the board, which unanimously adopted it and its many action items. One unanimous and unexpected recommendation that resulted from the planning process and excited everyone was a call for steps to consider finding a site and raising funds for a new symphony hall. This is being enthusiastically pursued.

When I first proposed this ambitious process to the Oregon Symphony, there were serious doubts that anything of real value could be achieved. As readers can see by the comments in the accompanying articles, the process worked. The resulting strategic plan and action agenda is a serious, supportable, and achievable document which has many proud parents. It has been a pleasure to work with them all.

Elaine Cogan is a partner with Cogan Owens Cogan in Portland, Oregon, and has authored two books. She holds a B.S. from Oregon State University.

How Are They Doing? Hartford and Pittsburgh Revisited

Over the past several years, the Institute has presented readers of Harmony an inside look at orchestra organizations that have undertaken extensive organizational change efforts. So the question arises: how are they doing? To find out, we hosted roundtable discussions with members of two of these organizations—the Hartford Symphony Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra—to review institutional status and progress. Edited transcripts of these reviews follow.

Hartford Symphony Orchestra:

A Work in Progress A roundtable discussion

In 1991, after a number of years of increasingly difficult circumstances, the Hartford Symphony Orchestra (HSO) went dark for 14 months. The orchestra resumed work under a compromise contract that called for, among other things, the establishment of 10 voting positions on the board of directors to be held by musicians. Those positions are still in place, and six musicians also constitute one-third of the executive committee.

As the orchestra approached a 1994 contract renewal, it used a facilitated process to reach an agreement. In the October 1997 issue of Harmony, we reported extensively on the Hartford Symphony Orchestra in a background piece written by musician board member Ann Drinan, a roundtable with participants in the 1994 contract-renewal process, and a brief essay on the “lessons learned” written by Paul Boulian, the organizational development consultant who facilitated the process.

Three years have passed since our report, and we recently gathered a group of HSO current and former board members to give us an update on the orchestra’s organizational progress. Following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Institute: To get us started, please introduce yourselves and describe your roles in the Hartford Symphony organization.

Ann Drinan: I am a violist with the HSO and the representative for the orchestra to the Regional Orchestra Players’ Association (ROPA). I’m a member of the board and have been since 1992.

Dwight Johnson: I am a past president of the HSO board and am currently a member of the executive committee.

Candy Lammers: I am a violinist with the orchestra, a member of the board, and currently chair the orchestra committee.

Arthur Masi: I am also a violist with the HSO and a former member of the board.

Millard Pryor: I am the president of the Hartford Symphony Orchestra board. Greig Shearer: I am principal flute of the HSO and a member of the board. Tom Wildman: I am currently vice president of finance of the HSO board.

Institute: Because this is not our first roundtable with the Hartford Symphony, Harmony readers know a good bit about your organization, its active efforts to bring about organizational change, and the long-term involvement of musicians in the governance of the orchestra. So give us an update as to how you are doing as an organization.

Pryor: In general, I would say that things are going very well. The good news is that we are making real progress in filling some organizational slots which have been unfilled, or inadequately filled, during the year. Our relationships, to my way of thinking, seem to be very strong. The bad news is that we ended the year with a small loss of $6,000, which reflected some incomplete budgeting and the lack of a director of development. I am optimistic about the next year, although we do have some strategic issues, the most important of which is what we are going to do about our summer series at Talcott Mountain. I am becoming concerned about the risk-reward ratio there.

Shearer: Millard has alluded to it, but I think it is important that your readers understand that the past year has been one of some administrative turmoil. Partly through coincidence, and partly on purpose, there has been a lot of turnover in staff. From a musician’s viewpoint, we have had a difficult operational situation because we have not had an orchestra manager. We’ve had the bizarre situation of having an orchestra manager who is living in California and doing his job by e-mail, if you can imagine! So there has been some frustration among the musicians which we think will be resolved shortly.

And one of our central issues is still to make sure that we try to involve more musicians in the process. There is still considerable reluctance among some of the musicians to get involved. There is still a sense among some that by being involved they are being co-opted. That is something that time will have to cure, and it is not as easy as one might like to think.

Those of us who are involved in the process, in the governance, are aware that there are limitations in our market and that people are doing their jobs as best they can. But there are still some musicians who think that things are not happening because people are not doing their jobs. Some of our frustrations are tied into our location in Hartford, which is having its own problems right now.

Masi: I would like to reinforce something that Greig just said about musician participation. Out of the 80 or 90 people in the entire group, we have pretty much exhausted the inventory of those who want to participate and serve. It is extremely difficult to get people who have not participated to even go to a board meeting. One of our challenges is to get people motivated and make them realize that they do have a voice and can make a difference. That is a major challenge.

Lammers: While I agree with Arthur and Greig, I have found that if I am working one-on-one with people, I can get them interested in specific tasks. If they are interested, they will go to meetings. For example, if the issue is touring, I am able to involve people who have been very vocal and very unhappy in the past because we haven’t done any touring. They are slowly beginning to understand that people do listen to what we, as musicians, say. It is a long, hard educational process.

Some of the musicians who are not involved are the very young players who came to the orchestra right out of school. So part of it is just an education and maturing process. Most of us were probably not that interested in governance when we joined our first orchestras because we were just excited to be in an orchestra and didn’t begin to realize everything that goes into actually running one.

Institute: Listening to you, it sounds as though musician and non-musician board members continue to work together well. Is that true?

Drinan: Yes, it is true. And let me give you an example. I am in charge of the ROPA conductor evaluation bank, and I talk with orchestras across the country that are doing music director searches, as we are. And I am thrilled and amazed at how wonderfully our system works by comparison. Greig and Tom are the co-chairs of our music director search—one musician and one non-musician. Candy and several other musicians are on the search committee, as are several other non-musician board members. We have a completely open sharing of information. What I have learned is that there are other orchestras that are doing searches where musicians are desperately trying to get their boards’ attention with evaluations of candidates, with no success.

We don’t even think about that issue any more. Cooperation is just the way it is. For us, a collaborative process is normal, and we need to be reminded that that is still somewhat unusual in the industry.

Shearer: We are arriving at a decision through consensus. Wildman: It is really hard for me to imagine doing it any other way. I think that

the symphony in Hartford would be in big trouble if we had proceeded any other way over the last few years, which have been difficult for many of the reasons Greig outlined at the beginning of this conversation. And when I looked back at the material that appeared in Harmony three years ago, it seemed like looking back to a distant time. The transformation in the governance of this organization has been huge in a relatively short period of time.

I do share the concern of the musician board members about the players who are not actively involved. Those who are involved are fully engaged in the process. They make substantial contributions to the organization and to the community as volunteers. At times, their work as board members puts them in awkward positions because they realize that not everything the musicians would like is attainable. If we have a tough issue down the road, I sometimes fear that not all of the musicians will be as committed to our process as those in this room are.

Johnson: I am gratified to hear that the musician board members feel that the process is still on track. Yes, there are still issues that we continue to struggle with. But I can’t imagine approaching those issues without the active involvement of the musician members of the board. It’s interesting to recall that not too many years ago, musicians were not given access to much of the symphony’s financial and other information, and some musicians believed that the symphony maintained two sets of books. Although we’ve got a long way to go, we have made important progress over the past decade.

Institute: What about volunteerism from the community? Are new people developing into leadership roles in the organization?

Johnson: Because we have a large board, the executive committee plays a key leadership role. In the last couple of years, we have brought some new people into the executive committee and I think that is a real plus. I have not seen any resistance by these new board members to the active involvement of the musician members. In fact, everybody seems to accept it as appropriate and natural. Is that a fair comment, Candy?

Lammers: I think it is. They are fascinated that we have voting roles. Seriously, really fascinated. They want to know what we do and to learn about the process. I explain that this is the only way we survived some very rocky times. We all need to be committed together in order to function. They accept that. “Wonderful” is the word I hear most often.

Drinan: We have a new member on the orchestra committee who has been in the orchestra for a long time, but not on the orchestra committee. At the last board meeting, he asked question after question after question. It was very gratifying to see some of the long-time, non-musician board members reassure him that asking so many questions was fine.

Wildman: I have to say that I have learned a great, great deal from the musicians involved. We all have. The musician to whom Ann referred has been consistently questioning the effectiveness of some of our marketing efforts. That is a very legitimate topic. Once again, I think this demonstrates the real benefit—not just the political benefit, but the real benefit—of the insights we get by having substantial musician involvement. It’s not a bad idea to have fresh views from time to time.

Pryor: Let me give you a concrete example of the real benefit of musician involvement. As part of our education effort, we went to see the superintendent of schools here in Hartford. One of the musicians who was part of our group brought his instrument. Right in the middle of the meeting, he played a small piece that was fabulous and a totally unrehearsed part of our presentation. I didn’t know why he had brought his instrument. I thought that he was on the way to a rehearsal. What an impact. What a masterful piece of marketing.

Johnson: Let me back up for a minute to our very talented player board member who asked some tough questions at a recent board meeting. He has a history of asking the tough questions and expressing opinions that to some board members may, at first blush, seem a bit outside the box. The questions that he asked concerning our marketing efforts made some of us uncomfortable. But we need that kind of input, and we “suits” have to keep our minds open to it.

Institute: Since we last visited, you have been through a contract-renewal process. How did that go?

Lammers: We have just completed year two of a four-year contract. The contract was done with an executive director who is no longer here and who, I think, really didn’t buy into the process. There were some wage increases, but not much other change. It wasn’t difficult, just frustrating, and we certainly didn’t break any exciting new ground.

Drinan: We had invited a couple of musicians to join us with the intent of showing them how the process works and perhaps helping them buy into the way we renew contracts as an institutional process. Among a minority of players, there is still a sense of needing to try to get back what was lost in the work stoppage of 12 years ago. And on that point, Arthur Masi did quite an assignment during our negotiations. Arthur, why don’t you explain.

Masi: I took on the task of looking at the wage scales from the prior contract and one contract before that, and comparing the increases over the years, and taking into account work stoppages, wage cuts, and so on. And I think one of the things we did that shocked management most during our negotiations was to come up with the wage level where we would have been if none of those things had happened. It wasn’t rocket science by any means, but it was obvious that no one in the administration had ever thought of looking at our situation from that point of view.

Drinan: What was interesting was how vehement some of the musicians were about “that is what I should be making.” They had no sense of “life happens,” or “life dealt us a bad thing,” or “this is more than 10 years later and can’t we get past it?” Even though Arthur spent a huge amount of time working with those numbers, the bottom line is that I don’t think we succeeded with those musicians. Maybe it’s only 10 out of 85. But there is still a small, but very vocal, group of players who cannot get past the sense of “what the symphony owes me.”

Wildman: I keep reminding myself that the full orchestra is about the same size as the law partnership of which I am a member. Almost never do we get agreement on anything. With that many people, you just don’t. Sure it is frustrating. But my guess is that there are a handful of people who will always be unhappy in this orchestra. That is just a reality.

Pryor: I did my first negotiation with the UAW when I was 24 and have had a lot of experience. I’ve never, ever found a circumstance where there weren’t a few people who just can’t get on board. I don’t think we will ever reach the point where there aren’t some naysayers. We shouldn’t organize our view of success as coming only when we get those people on our side, because we won’t.

Lammers: I would agree that we will never please everybody. But those people who hold their opinions long and hard serve another function. That is to remind those of us who are deeply involved how other members of the orchestra may feel. One night when Dwight was addressing the orchestra, I sat in the back of the hall, and was amazed at the different feelings coming from the musicians. It was a reminder that I have tried to retain. I need to step back and think of things from the viewpoint of a musician who is not involved and doesn’t necessarily care to be. If you cannot do that, you cannot ever hope to communicate effectively with those people. This process is difficult. It makes you think about and clarify the ways in which you deal with your colleagues.

Institute: Very well put, Candy. Now, let’s shift gears and turn our attention to how the Hartford Symphony is viewed in the community.

Pryor: When we are out seeking money, there are a certain number of people who remember the lockout with great displeasure and will not be distracted from it. The search for a new music director has opened up some people to look at the orchestra with more interest. We’re in better shape, but I can’t say we’ve made great progress.

Lammers: Millard is right. We have made some progress. We have done some social events tied to concerts that have been important steps in our money- raising. But I still don’t think the community understands that this orchestra is resident in the community. We pay our mortgages, our kids go to school here, our musicians teach music to their kids. We’re still too self-effacing. We don’t toot our own horn nearly enough.

Johnson: Recently, I have noticed that even some of the people who retained bad feelings from the lockout have been much more favorably inclined to contribute to the symphony, in both time and money. Almost all of the comments I receive are very favorable about the new relationship. This is a real plus and will continue to be a plus as it develops and becomes better known.

Wildman: I would agree with Candy and Dwight. Those who think about our recent progress think in increasingly positive terms. Our main challenge as an organization is by no means unique to Hartford. And it doesn’t have much to do with our system of governance. Our challenge is to interest a wider constituency.

Institute: And how about a quick review of your current financial situation. You mentioned a small deficit for the year that just ended.

Johnson: We’ve actually done quite well since our last conversation. Although we did have a small deficit this past year and are concerned about the coming year, in recent years we have generally been balancing our budgets. This is in part because of the extraordinary performance of the stock market. Unfortunately, we cannot count on it to perform similarly in the future. In addition, like most of our mid-sized peers, we have not figured out how to close the gap between what we would like to have available and what we do have available. That brings me back to broadening our constituency. I agree with Tom that we need to increase our support both in terms of performance revenue and in terms of contributed revenue.

Institute: We are nearing the end of our time together, but let’s take a moment to look ahead. Share with our readers your thoughts looking forward over the next few years.

Shearer: I want to respond to something that was said earlier. Because I am on the inside of the process, I find myself focusing on simply being able to continue as we are. We have succeeded tremendously if we can end the year with a balanced budget. But within the orchestra are a significant number of people who feel that their desires for increased service guarantees and increased compensation have been put on hold for many years. They’re frustrated that we are simply staying in the same place, whereas those of us who are involved in the process are relieved by that fact.

Pryor: Greig, I think we have some real opportunities. It is my observation that our development efforts have not fully matured, and that with the revisions in our staffing we have reason to be optimistic. We have also talked about marketing and I think we have some new opportunities there, too. The third area that gives me reason for optimism is touring. We have received a $200,000 grant from the state to play concerts outside Hartford and we are going to seek additional funding.

Having said that, we need to remember that this is Hartford, Connecticut. This is a small market that is close to New York and Boston and people have many entertainment options. But I hope the things I have outlined will allow us to meet the basic requirements of a group of people who are not well paid, which the board understands.

Drinan: A lot of players are very interested in Millard’s concept of us being the “Connecticut Orchestra” rather than the Hartford Symphony. Not that we would change the name, but there are areas of the state that are underserved. It is possible—if we can find the venues and secure local assistance with marketing— that we could expand the full orchestra’s schedule by four or five concerts a year, even if we just run out existing concerts.

Lammers: As you can see, there are a lot of forces pushing and pulling on us. And I would add our music director search to the list of reasons to be optimistic. We hope that the person we select will help give us some impetus, some direction.

Johnson: I, too, am optimistic about a new music director. The response has been very strong and we’ve seen excellent candidates. And I would wrap this up by saying that although we have a long list of things to work on, we need to remember how far we have come. Of course we have made mistakes. But we have also done a lot of things right. And, most importantly, we are all willing to keep trying.

Institute: We thank you for taking the time to give us this update. The Institute lauds your continuing efforts toward being an effective symphony orchestra organization.

Cultural Change in the Pittsburgh

Symphony Organization A roundtable discussion

The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO) faced harsh fiscal realities in early 1997. The orchestra formed a task force to review a revised business plan. A member of that task force, Tom Witmer, a PSO board member

and chief executive of a company widely recognized for its approach to total quality management, suggested the use of a Japanese planning method, “Hoshin.” The PSO adopted this technique to address specific goals toward which musicians, board members, volunteers, and staff could work jointly.

In the October 1998 issue of Harmony, we reported on the early stages of the use of the Hoshin process. Two years have passed since the Harmony report, and three years have passed since the PSO’s first Hoshin meeting. The Hoshin facilitation team recently met with the Symphony Orchestra Institute to review the organization’s progress, current status, and future outlook.

Institute: We are eager to learn of your progress since you adopted Hoshin. So please introduce yourselves and we will begin.

Scott Dickson: I’ve been with the orchestra for three years, and am currently the PSO’s manager of the Pops and Heinz Hall Presents series. I hold degrees in piano and voice performance and maintain an active performance schedule as an accompanist.

Hampton Mallory: I am a cellist in the orchestra and currently chair the Access Music team. I am also a board member of the American Symphony Orchestra League.

Ron Schneider: I am a horn player, and have served as chair of the orchestra committee, a representative to the PSO board, and a member of the board of advisors of the Symphony Orchestra Institute.

Linda Sparrow: I am vice president of education for the Pittsburgh Symphony Association, the orchestra’s largest volunteer organization. And I am also chairman of PSO Outreach for the Northern Allegheny area.

Bob Stearns: I’m the president of an organizational development consulting firm and the director of human resources for CoManage Corporation. I also serve the PSO as its Hoshin facilitator. My professional life is dedicated to developing and implementing strategies to develop high performing organizations.

Kathy Kahn Stept: I am a member of the executive committee of the Pittsburgh Symphony Society board and chair of the volunteer leadership committee.

Tom Todd: I am currently president and CEO of the Pittsburgh Symphony Society. In my “day job,” I am a partner with a law firm, practicing in the area of mergers and acquisitions.

Gideon Toeplitz: I have been executive vice president and managing director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Rudolph Weingartner: I am a member of the Board of Advisors of the Pittsburgh Symphony. I’m a retired philosophy professor, former dean of arts and sciences at Northwestern University, and former provost of the University of Pittsburgh.

Institute: Think back and explain to our readers what life was like in the Pittsburgh Symphony in pre-Hoshin times.

Toeplitz: Before we started Hoshin, we were in the same position that many of our orchestral colleagues are today. We focused very much on labor relations and tried to resolve a lot of unnecessary confrontations. Our energy was going in directions which were not very productive for the organization as a whole.

Mallory: Our focus before Hoshin was always either on the present or the recent past in terms of political activity—of which there was a lot between the orchestra musicians and management. The musicians tended to be in the position of reacting to what we thought was either inattention or overt malice on the part of management. There was neither a time nor a vehicle to do anything different about the future.

Todd: During my first year on the board, we were in the middle of very difficult labor negotiations which came very close to a strike. I remember Hampton Mallory, who was then chair of the orchestra committee, speaking to the board. At that time, the idea of the orchestra committee chair speaking directly to the symphony board was probably unprecedented. Hampton was eloquent and nonconfrontational when he spoke and I was really impressed with what he had to say. The point is that this was the first time we had a chance to talk with a musician about the issues facing our organization. Quite frankly, I’m surprised that we did as well as we did back then.

Schneider: Without meaning to sound flippant, I can cite one objective measure. Before Hoshin, the musicians’ union legal bills were much higher. There were always grievances on the table. There was not a lot of trust and cooperation in this orchestra.

Sparrow: I’ve been a volunteer here for 10 years, and before that had been an orchestra volunteer in Toledo and Indianapolis. It was much easier to interact with the smaller orchestras. At the Pittsburgh Symphony, I felt I was a nameless, invisible person who worked in the building regularly. I was never acknowledged by senior staff and had no interaction with the orchestra.

Institute: Let’s move forward to today. Describe the changes that you see since you implemented Hoshin.

Sparrow: Hoshin has become much more than a planning technique for the Pittsburgh Symphony. It has also become synonymous with our culture. We have keystone principles such as the fact that every member of every constituency is important and is capable of bringing valuable ideas and insights to the organization. Communication is absolutely the glue that holds the organization together. And it is really okay to have differing opinions. The four constituencies must act together as a team. Today, we are really working together and having fun.

Dickson: I want to emphasize the word “team.” I joined the Pittsburgh Symphony just as we were beginning Hoshin. And I would observe that everybody has taken a psychological ownership of the institution. We do everything together— all of the constituencies—as a team effort. We communicate openly, we listen, and sometimes we disagree. We take the time to talk out our issues and ultimately come to better results.