Be An Entrepreneur! Get Outside Your Comfort Zone!

How many times have we musicians heard those phrases? Do they mean that we should try to be like Janice Martin, the violinist who plays while hanging upside down? My most recent experience is not quite that dramatic…..

“What time is the lunch break?” I asked the stage manager, knowing that he was the one with the answers.

He looked at me blankly, then explained, “We don’t have a lunch break. It’s only a five hour call today, so we have two 10-minute breaks. That’s it.”

It was Saturday morning at 11am, and I had been counting on going out to grab a bite during the assumed lunch break*…..but 10 minutes isn’t long enough to do that, it’s just time to use the bathroom, fill your water bottle, and step out of the building for a breath of fresh air. I drank a lot of water during breaks and soldiered on until we let out at 4pm.

The production I was involved with was a staging of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” (yes, the dark, twisted novella that you probably were required to read in high school). We had 4 weeks of rehearsals (30 hours/week) and 10 performances (90 minutes each, without intermission). I’ve never heard of a professional orchestra devoting 120 hours of rehearsal to anything, not even the thorniest new commission. I quickly learned that rehearsing an orchestra is different than rehearsing a play, the biggest difference being that musicians do most of their practicing at home, with the bulk of rehearsal time devoted to combining their efforts into a whole.

“Why would a theater company hire a cellist?” you might well wonder. Composer/cellist Hugh Livingston composed a soundscape for the production, but other commissions intervened and prevented him from being there in person for Kafka. The theater group decided to hire a local player to fill in the gaps.

Why me? Because I had just retired from the National Symphony Orchestra, and because I had performed a solo show at the 2013 Capital Fringe Festival, called “In Search of the Perfect G-String.” I’ve also performed several times with a local dance company. Those experiences meant I came up on someone’s radar. Phone calls were made, conversations ensued. When the soundscape was mentioned I made sure there was no confusion: “If you want someone who can improvise, I’m not that person.”

Two months after those initial conversations, we’ve just completed a 10-show run of “Metamorphosis.” During its 90 minutes, I played approximately 40 sound cues, at least half of which I wrote or improvised; the rest were adapted from existing music. Entrepreneurial? I think so. Outside my comfort zone? Definitely, at least to start with.

It’s not a new idea to add music to a staged work. Mendelssohn’s “Incidental music to Midsummer Night’s Dream” is a perfect example; so is Grieg’s music for “Peer Gynt.” Wikipedia has an entry on incidental music that breaks it down into sections, such as Overture, Loop, and Stinger. I used all of them. I became less afraid of creating music for the play when I realized I could draw on my repertoire of symphonic works. Mendelssohn, Grieg, Tchaikovsky, Mozart–those guys knew what they were doing!

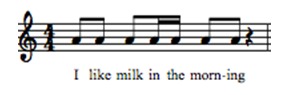

One day in rehearsal the director said she wanted a “song” based on the words, “I like milk in the morning.” During a very boring stretch of highway driving, I diverted myself by thinking about The Milk Song. The syllables suggested a simple rhythm:

Soon after, a banal tune came to mind (I thought of the repetitive theme in Shostakovich 7th.) My little tune quickly turned into a full-blown song, which was expanded into “the milk scene.” That’s just one example; there were others throughout the play.

As for the improvised sections, it wasn’t like jazz improv, where each player expands upon a theme and interweaves it with what other players are doing; this was more like inventing sound effects for a film score. The director wanted music for a fight scene, so I thought about the fight scene in Tchaikovsky’s “Romeo and Juliet” (rapid 16th note runs), and the sword fight in Prokofiev’s “Romeo and Juliet” ballet (ponticello chords). I soon worked out similar musical gestures for “Metamorphosis.”

The closer we got to performances, the more I saw tiny differences between the orchestra culture I was used to, and the culture of the theater world. For instance, Actors Equity, the actors union, has strict rules about fight scenes: before every performance, each fight has to be practiced with the stage manager present. This rule ensures that the movements haven’t changed, and that they are still safe for the participants. It gets even better: there are fight coaches! I can’t wait for The New Yorker to run a profile about Stage Combat Fight Masters — now that would be a great read!

One of the more amusing parts about working with actors concerns “giving notes.”

“I’m not giving you a note, but I do want…”

“I can’t remember your last note…”

“I’ve given that note three times…”

For actors, “notes” mean director’s changes. They might be movements, or tone of voice, or blocking, or even suggestions about the mood being portrayed. Actors are not allowed to give each other “notes” — that would be unprofessional. Once the run of performances starts, it becomes the stage manager’s job to give “notes” to the actors.

Yes, there were times when I felt like a ‘stranger in a strange land’, but I was also struck by how many things we had in common (besides “notes”).

In fact, the more time I spent around actors, the more I got to wondering: why don’t actors and musicians study together in school? Wouldn’t it be useful training for actors to learn the gestures of music? And wouldn’t it be helpful for musicians to learn some tricks of the actors’ trade? Great musicians make you hear the simplest melodies as though you’ve never heard them before…actors do the same with texts. I think there’s a lot of room for fertile interactions, and I personally hope to do more in the future.

* Here’s the typical rehearsal scheduling that I was used to:

A “double rehearsal” for the NSO runs from 10:00 – 12:30, with a 20 min break; there’s an hour off for lunch; then another rehearsal from 1:30 – 3:30 with a 15 min break. We had a maximum of 5 rehearsals + 3 concerts during a subscription week.

You know, I totally agree! As many years during my youth were spent onstage as they were in the concert hall. Once I had been a Director’s Musical Director, I became their first call for the next project – because I spoke their language and we could converse and ‘get’ each other. There are many parallels, and we should add dancers into the mix, too. A school of the performing arts gets my vote over a school of music or dance or drama any day (and I went to one such conservatory!)

Thanks for sharing your experience – most enjoyable!

http://www.stephenpbrown.com