The most interesting conductor in the world

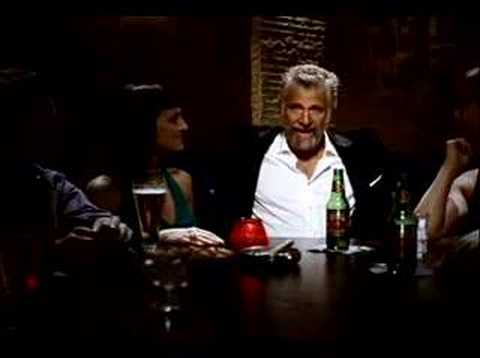

Dos Equis, the Mexican beer company, recently ran an ad campaign around a character they dubbed “The Most Interesting Man In The World” (my favorite ad was this one). It was, among other things, a take-off on how the press love to anoint individuals, or institutions, as the “best” or “worst” or “sexiest” or pretty much anything else that will sell newspapers and magazines and radio advertising.

Every so often the press go on a “best of” binge in our business as well. The latest examples come from the English press; the Observer has anointed Valery Gergiev the greatest conductor of his generation:

Even those who disagree concede that he is the most electrifying. His high profile internationally is based on his spellbinding effect on audiences and musicians alike – not to mention his famous performance of Shostakovich’s Leningrad symphony to an audience of Russian soldiers and tank commanders amid the ruins of the capital of his homeland, Tskhinvali in South Ossetia, after fighting between Russian and Georgian troops…

In terms of sheer, thrilling unpredictability, a Gergiev concert is the musical equivalent of what it must be like in the seat of a racing car rounding a hairpin bend and holding the road; again, not only for the audience – it is like that for the musicians too. “I doubt we will see another conductor like him,” says Noel Bradshaw, who has played the cello with the LSO for 25 years, “during this generation, if ever.”

Is Gergiev a major conductor? Unquestionably. But by what criteria is he “the greatest of his generation”? And why do we need the Observer to make these determinations for us?

Along the same lines, the Daily Telegraph has decided that the Chicago Symphony is “America’s finest orchestra“:

The orchestra’s rise to fame began with the great Fritz Reiner in the Fifties, but it was during the 22-year reign of the fierce Hungarian George Solti that the orchestra became the brawny yet subtle precision instrument that it is today, famed especially for its noble and stupendously powerful brass sound. A recent orchestral poll in Gramophone magazine named it as the best American orchestra, and fifth in global terms.

To be ranked ahead of the New York Philharmonic was sweet indeed for this city, always chippy about playing second-fiddle to the Big Apple.

Times are tough for American orchestras. For years audiences have been ageing and falling in numbers, and at least a dozen US orchestras have gone to the wall in the last decade. All this is familiar to British orchestral managers, as is the orchestra’s determination to “add value” to the concert experience by putting the music in its cultural context. What’s unique about the CSO approach is its combination of razzle-dazzle and high-mindedness. Three times a year it hosts Beyond the Score, a “cultural portrait” of the evening’s main work combining theatre, film documentary and commentary. These have been so successful that several orchestras in the US and Europe have syndicated them.

I hope there’s no one in our business who doesn’t realize that 1) rankings like these are meaningless, whether of conductors, orchestras, or instrumentalists, and 2) that articles like these are the product of a great deal of time and money spent by those anointed as “the best.” No doubt such articles serve a purpose in promoting the appearances of the anointees, and selling tickets is always a good thing. But I suspect there is damage done as well, both to institutions and musicians less able to spend the resources necessary for this kind of publicity and to the public’s potential understanding of our business as something more than “Transatlantic Idol.”

As Ray Ricker so wisely pointed out in his opening post yesterday, “don’t believe everything you read.” Press coverage of our business, and especially of the performers and the music they perform, too often proves what the screenwriter William Goldman once famously wrote about his industry – “nobody knows anything.”

No comments yet.

Add your comment