Toledo Symphony Orchestra

About the Ensemble

Formed in 1943 as The Friends of Music and incorporated in 1951 as the Toledo Orchestra Association, Inc., the Toledo Symphony has grown from a core group of twenty-two part-time musicians to a regional orchestra that employs nearly eighty professional musicians who consider the Toledo Symphony their primary employer.

In the 1960s the orchestra formed ensembles in each instrument family and continued their community outreach programs. Their endowment began to grow upon receipt of a Ford Foundation gift. By the 1970s the TSO’s budget had grown to $1.8 million, and Music Director Serge Fournier stepped down after leading the orchestra for 15 years; Yuval Zaliouk was named the seventh Music Director in 1980.

A core of 22 musicians was formed in the early 1980s, and several Principal players moved to Toledo, and the orchestra was able to attract the first professional harpist to live in Toledo. The orchestra started to expand its neighborhood community concerts, and established the concert series that continue today: nine pairs of Classics concerts at the Toledo Museum of Art Peristyle, six Pops concerts at the Stranahan Theater, five concerts in the Mozart and More series at Lourdes College, four Family at the Museum, and many, many chamber, neighborhood, and regional concerts.

In 1990 Andrew Massey was named the eighth Music Director; he conducted the Toledo premieres of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony and Britten’s War Requiem. The TSO commissioned new works by Charles Wuorinen and Stanley Cowell. By the mid 90s the budget had grown to $3.8 million and the endowment exceeded $6 million.

During the past decade the TSO enjoyed many guest conductors, finally resulting in the appointment of Stefan Sanderling as Principal Conductor and Chelsea Tipton as Resident Conductor in 2004. Mstislav Rostropovich was perhaps the most significant musical guest of the decade; he first appeared with the TSO in 1998 and returned at his request in 2002 as part of his 75th birthday tour. Stefan Sanderling conducted a special tribute concert on September 11, 2002, the first anniversary of the 9/11 tragedy. It was a deeply moving musical experience for all involved.

Nine area composers were invited to participate in Orchestra’s 60th Anniversary Fanfare Project in 2003-2004. This resulted in the commissioning of nine new fanfare works for orchestra, composed by TSO musicians, university faculty members, and music students. The TSO’s community and educational outreach expanded, including a program funding music teachers for students at the Toledo School for the Arts and the Music In Our Schools program.

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation invited the TSO to submit proposals to participate in its Orchestra Forum project in 2000. Toledo was only one of two ROPA orchestras (the other being Richmond VA) to participate in the Forum. The Mellon Foundation has provided the TSO with over $2 million over nine years in support of innovative programming, musical activities and the endowment fund. Funding from the Mellon Foundation has assisted many TSO musicians with career enhancing grants and unique professional development opportunities.

This coming season marks the 65th anniversary for the Toledo Symphony. Polyphonic congratulates the TSO during this historic year!

[Ed. Note: In April 2000, Harmony published a roundtable discussion with some of the Toledo musicians who worked on staff at that time (several of whom are still on staff). To read the Harmony roundtable discussion, click here.]

Ann Drinan, Senior Editor, June 2008

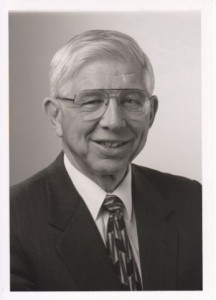

An Interview with Robert Bell, President and CEO

Bob Bell celebrated 50 years with the Toledo Symphony Orchestra (TSO) in 2006. In 1956 he auditioned for a percussion position with the TSO, and eventually became the Principal Timpanist with the orchestra. In the 1960s he took over the personnel manager and librarian duties and eventually became interim director. In 1984 he was appointed to his current position.

Ann Drinan: Tell me about the city of Toledo – who are your major arts competitors?

Bob Bell: Geography is not a major issue. Cleveland and Detroit are nearby, but Ann Arbor is really more competitive than either of those cities. Ann Arbor brings in major orchestras for their Choral Union series, but they have scaled back. They still bring in Berlin, New York, San Francisco, etc., but they now also do a potpourri of things. Toledo is its own city – we don’t feel that we need to compete with The Cleveland Orchestra.

The quality of life in Toledo is excellent because of the museum and our parks. It’s a very comfortable, safe, and affordable city, easy to get anywhere in 15-20 minutes. The population is about 300,000 plus 500 – 700,000 in the suburbs.

AD: What’s the history of the TSO?

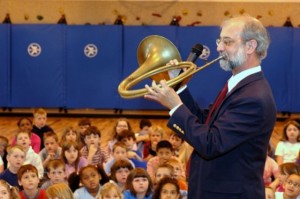

BB: We’re now celebrating 65 consecutive years! We first started the core in the late 1980s, with a string quartet that went into the schools. In an effort to find more meaningful ways to increase musician compensation, we created a brass group, then woodwinds, then percussion. Now we have all those groups, plus a small 18-20-piece chamber group who do outreach school concerts. We’ve advanced ways to make it a more attractive position for professional musicians. In general, we’ve tried to anticipate the expenses with revenue/ income sources.

The important thing is the willingness of the musicians to participate in these rather unusual work environments. Some orchestras wouldn’t even consider doing some of the things we do – we’ve built a culture over the decades so that people just accept that we do this.

We play our main series at four different halls. The main one at the Toledo Museum of Art has 1500 seats. We play our Pops concerts in the Stranahan Theater; it has 2400 seats. We do our Mozart series in an 800-seat hall. We do pretty well in filling these halls, but the concerts in the neighborhoods and runouts are always at 90% to 100% capacity. This builds an appreciation for the orchestra and the music – they present us so they have a vested interest in making us a success. It connects us to the community in special and unique ways. Do they become regular subscribers? Some do…

AD: Where do your musicians come from?

BB: When we started to do this in the 1980s, 80% of our Principal players were freelance musicians from Ann Arbor or Detroit. We’ve reversed that, such that now we have no non-resident Principals. Our core players are living in the community, and we’re approaching 50 in the core. Part of the negotiation process is that we’ve tried to add services while putting in a foundation to justify it. We have a supportive board leadership who has been mindful of what we’re trying to achieve. We’ve had many financial crises over the years, but we’ve never had a labor stoppage and never missed a payroll.

We function as a community, a family. We’re in the second year of a 3-year contract; we never have hostile negotiations. Years ago both sides had attorneys (nothing compared to some other orchestras), but our last negotiations were completed without a union representative at the table and with no lawyers. The union signed the contract, of course, but the Orchestra Committee did the negotiating.

AD: What is the relationship of the Toledo Symphony with the city of Toledo?

BB: We have embedded ourselves into this community in ways that Cleveland or Detroit could never provide. There’s that old debate about “are orchestras dead?” I was always amused by it – more than 25 years ago, Ernest Fleischmann was talking about a community of musicians, 1 or 100, doing what it takes to be part of the musical fabric of the community by playing in churches, community centers, and so on. There was a period when we drifted away from this idea, but we resumed it with vigor in 1985. As a result of that, we have a tremendous workload in non-core Classic concerts.

Our musicians will do 400 to 500 services a year (in aggregate). We do the basic pairs of Classics, a Family series, Pops, etc. – 40 to 50 concerts in our main halls. But we do another 50 actual concerts where we’re playing in community centers and churches throughout greater Toledo. We repeat the performances at multiple venues, and we find new places every year. We also are hired by the Toledo Ballet, Opera, and Choral Society. We earn about $500,000 of our budget from these concerts.

For example, we do a neighborhood concert at Westgate Chapel as the beginning of their series. We use 50 or 55 musicians, though sometimes we reduce it. We use core repertoire so we don’t need a lot of rehearsal time. And we may change conductors a few times.

AD: That’s fascinating. Tell me more about these neighborhood concerts.

BB: It started back in the 1970s when we went into the inner city theaters. We had a grant to do this. They’re lighter concerts; in December we do a dozen or more of these concerts, plus the Nutcracker & Messiah. There might be 80 services in December. I’m always delighted when we can run out a repeat of a regular concert – we do have one venue where we do three concerts at the University of Finley. We’ll also repeat a Mozart concert there.

The symphony doesn’t sell tickets for these concerts; the venue does. The church or community center buys us and may use the concert as a fundraiser, though some present the concert for free. A church can raise $40,000 to 50,000. We have a person on staff (our co-principal horn) whose job is to sell these concerts.

We wanted to find ways to provide more income for our musicians. We knew that it wouldn’t be by expanding the Classics series, so we found other work so we could guarantee it in the musicians’ contracts. But we knew we had to repeat it and continue to sustain these income sources because once we made the commitment to the musicians, we never backed away from it. Those services remain part of the guarantee. Our chamber groups perform a wide variety of services, such as weddings, business meetings, receptions, etc., as part their service guarantee.

We’re being much more relevant in our community by not playing at the places where only tony suburbanites would come, and because we touch the lives of a large part of the community and region. This facilitates interest in the institution, and we find individuals willing to make substantial financial contributions to the orchestra.

AD: Tell me about the Mellon Orchestra Forum – what caused them to select Toledo as one of only two ROPA orchestras included?

BB: We believe we exemplified the basic values they were looking for in our internal culture:

- to integrate the full TSO community into the institutional vision,

- to develop a lively and diversified work environment that promotes job satisfaction using musicians as artistic resources, and

- to strengthen the bonds between the orchestra and the community.

We didn’t change a lot because of Mellon but it fueled our opportunities to expand the things we thought were important. We want a nourishing and productive work environment for the musicians. This doesn’t start with a financial bottom line but rather an artistic.

We used the Mellon money over the nine years to strengthen what we’d already started. We actually took tens of thousands of dollars and set up a program where musicians could apply to us for a Mellon grant for professional development. For example, our Assistant Principal viola went to study in Italy. Mellon gave us $1.8 million over 9 years, and then they gave us an additional $500,000 as a matching grant for our endowment.

The key things we did with the Mellon funds: professional development grants and to pay for featuring our players as soloists in runouts and regional concerts. One season we had 22 of our musicians perform as soloists.

AD: When did musicians start working on staff? Was it a planned policy or did it just happen?

BB: No musician salaries are enough. When we would have a staff need, given that musicians are well trained and capable, it seemed more logical to look within the family to help musicians have an income. Many didn’t work out: sometimes it didn’t fit well for the musicians, sometimes they didn’t have the skills. But we’ve had a lot of successes. If you ask someone to do something new and they’re good at it, there’s a great level of satisfaction at doing a good job. When we have a job that we think someone in the orchestra is qualified to do, we offer it to the musician first. Currently we have five musicians on staff, minus the librarians and personnel manager – nine all together.

AD: How would you describe the current health of the orchestra?

BB: It’s never been better – the endowment is approaching $20 million (including pledges). In order to make it work, we need to double the endowment; we’re in the middle of a $15 million campaign (with $5 million already pledged).

Our accumulated deficit is about $300,000 now; however we may add more to that when we finish the fiscal year June 30th. Mellon is going away next year ($200K a year), and another key foundation grant is being reduced. So we’re looking at a significant challenge next year – initial projections show a 2% increase in expenses and a 7% reduction in income.

We have a $6 million budget with about $25,000 as the core salary. We look for ways to give musicians more money – they can work on the staff, play a solo, join a group. Most people are not paid the minimum; we’ve rewarded people who were making the biggest contribution in terms of their playing responsibility and their leadership roles.

AD: Congratulations on your 50+ years with the Toledo Symphony Orchestra. I can tell how much you care about the organization and its musicians.

An Interview with Merwin Siu, Principal Second Violin and Artistic Administrator

Merwin Siu joined the Toledo Symphony in 2000 as Principal Second Violin and has soloed frequently with the TSO. He recently appeared as soloist in the TSO’s presentation of Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra, and will be featured next year as a soloist in a work by Keith Jarrett for violin and strings. Merwin also serves as the Toledo Symphony’s Artistic Administrator, coordinating artistic input from conductors, musicians, and audiences for subscription series concerts, outreach appearances, and educational performances alike. Merwin is the founder and director of Project Aeolus, Toledo’s newest voice for contemporary music and performance art, and is an avid chamber music performer. Merwin holds a Masters in Music from Indiana University and degrees in English and Music from Montreal’s McGill University.

Ann Drinan: How did Toledo Symphony musicians start working on the staff?

Merwin Siu:

I can only speak to how I took on my staff role. It started out because the Toledo Symphony was going through both a principal and a resident conductor search simultaneously – we didn’t have artistic leaders determining our programs, especially for the neighborhood and runout concerts. Bob [Bell] approached the musicians about possibly filling this artistic gap internally during the search period. I took on a position that has evolved into my current Artistic Administrator position. It seems so natural to me that it always surprises me that it has happened so rarely in other orchestras.

Having musicians on staff helps us deal with little things on the ground level, so they don’t escalate into larger problems. And it makes our working environment more sociable. It’s hard to put a value on it but over the course of a season, it can lead to a better attitude.

Having musicians on staff is part of our culture now. For example, if a musician wants to play a solo at a neighborhood concert, it’s easy to express that to management – just come and tell me about it!

There’s always a potential for conflict, of course. We did a side-by-side concert with a local university – it was a difficult situation for a variety of reason, so there were complaints. In this case the musicians complained to our bassoonist who is on staff. She brought the issue to a staff meeting, and we were able to address these concerns almost immediately. Without the musicians on staff, management may never have heard about the problems at this concert.

Another good thing is that non-musician staff feel more involved with the players – particularly middle-level staff. Staff musicians share stories about what happened at a rehearsal or concert; this makes them feel more a part of the orchestra.

AD: Tell me about the TSO’s involvement in the Mellon Orchestra Forum initiative.

MS: It was hugely valuable for me personally. Prior to participating in Mellon, there was very little perspective or context for me – there are no other violinists acting as Artistic Administrators. I had a unique sense of what it’s like to wear more than one hat. The Mellon meetings helped me interact with people from a variety of different orchestras – it was great for networking. And I responded even more strongly to some of the non-musical ideas presented.

For example, Edward de Bono did a presentation about his Six Thinking Hats concept – it’s a way of disciplining group thinking so that people are thinking in a particular way at a particular time. It’s very helpful to keep brainstorming meetings on track.

I went to the Mellon meetings fairly often – we usually brought 2 or 3 musicians. Several senior staff members and a board member would also attend – we rarely had implementation-level staff. I was going as a musician, but it was particularly interesting for me to think about the implementation of some of the ideas that were presented. We were fortunate to have a lot of people interested in going – we covered a large portion of the orchestra, and rotated attendance through the board as well.

Whether you liked it or not, Mellon entered the industry with at least the openness, if not the actual predisposition, towards change. They wanted us to be open to relatively large-scale change. If one is contemplating possible change, there should be some sort of visceral reaction to that. What does this mean? I’m relatively new to the field, so I walked in to these meetings without a sense of history or rooted distress.

Mellon came at a time when there was a chance for the orchestra to really grow. A lot of orchestras saw that possibility in the early to mid 90s. Mellon gave us opportunities – we grew the core in the number of actual players with core contracts, especially in the string section. We have some really involved board members who, because of this process, interacted with a lot with musicians. The core relationship of our board and musicians increased significantly over the course of our participation in Mellon.

AD: Because of your Mellon grant, you were able to offer professional development grants to your musicians. How did the musicians typically use these grants?

MS: This was really, really fun. Basically we allocated several tens of thousands of dollars from the pool of Mellon money and offered it to the musicians. Only tenured members could apply, and the ideas ranged pretty widely. For example:

- One musician published a scale book.

- I started a new music series in the summer. We brought in Bright Sheng to do John Adams’ Chamber Symphony; we had an alternative rock band; we played for silent films; we did a violin and dance collaboration. It was great!

- Our Assistant Principal violist went to Italy to study a Hindemith sonata.

- A composer applied for software to enable his composing – the orchestra then performed his piece.

- Our Assistant Principal clarinetist applied to do a chamber concert, Inner Voices, of unusual combinations of non-principal players. After this performance, we began including non-principal players in our chamber concerts.

- We brought in a breathing specialist, who gave private coaching and group master classes for winds and brass. This has become a biennial event.

- We participated in a neighborhood parade near the office – we contributed a float (flat-bed truck) and the musicians helped decorate it. It was great for helping to connect the orchestra to our community.

- We sent people to national and international instrument conferences

- Our flute section presented two flute festivals, bringing in internationally-renowned performers to interact with over 100 students throughout the region in lessons, masterclasses, and seminars.

The grants are sanctioned by the orchestra but not supervised closely, so the musicians have a great deal of independence to do projects that aren’t necessarily connected to the orchestra – this gives them both safety and freedom.

Mellon did a matching grant for us [in addition to our regular Mellon contribution] – we solicited funds for the endowment that will hopefully continue to make these professional development grants possible. We certainly intend to continue them.

AD: Bob Bell tells me that last year 22 TSO musicians soloed in concerts. Describe how you decide who gets to solo.

MS: At first, the players would come and suggest playing a concerto. We talked about making it more formal and requiring auditions but, to this point, we haven’t needed to do that. We have always allowed Principals and Assistant Principals to play solos – generally the players who are interested in doing it are also quite capable of doing it. Recently we’ve encouraged section players to put themselves forward. And we’ve been encouraging section players to participate in our chamber series.

AD: Explain how you price the neighborhood concerts you do.

MS: There’s a huge price range – at some of the venues we do it for just a few thousand dollars. For example, we work with an inner-city church for very little income, but this gives us unusual collaborative possibilities. We’re fortunate in that some venues have a long-term relationship with us – we’ll do a full orchestra concert, a chamber concert, and a Pops concert. Those fees are higher. But we don’t go above $18,000 or $20,000.

We don’t think of them on an individual basis but rather as a way to offer our musicians better salaries – to fill out their service guarantee. If we’ve promised 200 services but we’re only using 180, we can use those extra 20 services at no out-of-pocket expense to us. Most of the time, we’re don’t go over the service guarantee, so we’re able to fold in these services.

We usually bring a stage manager and an operations person, and we use volunteers to help as our stage crew. One of our horn players is involved in selling the concerts to the venues; she gives them lots of advice about how to market the concerts.

AD: So you don’t worry about whether you lose money on any specific concert?

MS: We don’t look at it in terms of P&L for each concert – assessing these concerts on an event-by-event basis doesn’t make sense. If we did that, we would make different programming decisions. Instead, we look at an annual aggregate. We take the amount of money we bring in and then delete expenses like over-guarantee services and music rental. It’s definitely more than $400,000 towards the bottom line. [The additional $100,000 Bob Bell mentioned comes from ballet, opera, and chorus services. AD]

It’s taken a while to build up the program – I don’t have the exact history, but there was a significant amount of door-to-door sales done 12-15 years ago to make this happen. Now so many churches and synagogues in our area have hosted concerts, it’s not considered an unusual event.

AD: Why is it important to Toledo that you do these concerts?

MS: It’s something that our orchestra has always needed to be very clear about. It’s important for us to make a specific case of community relevance – The Cleveland Orchestra and the Choral Union series in Ann Arbor, our main competitors, couldn’t do this.

I’m more and more impressed with how focused our mission is. It’s not just about being relevant to the community – it’s also about how having an orchestra of resident professional musicians enhances the life of the community. This has only been true for the past 25-30 years. We constantly strive to be clear about that to Toledo. We’ve also been lucky in that we’ve had board members willing to advocate for community relevance as well – it’s not about just bigger concerts and bigger stars.

An Interview with Alan Taplin, Hornist and Orchestra Committee Chair

Alan Taplin has been a member of the Toledo Symphony’s horn section and brass quintet since 1981, and he has been an arranger for the symphony since 1980. Alan has performed with the Detroit Symphony, Louisville Orchestra and the Des Moines Metro Opera. He is very active as a freelance/chamber musician in Ohio and Michigan, and has recorded commercially in Detroit, Chicago and Toledo. He holds a Bachelor and Masters degree from the University of Michigan in horn performance. He has served on the faculties of Olivet College, Concordia College, Heidelberg College, the University of Toledo, and Hillsdale College. He lives in Springfield Township with his wife Carrie (also a horn player – Michigan Opera Theater), his daughter Emily 16 (also a horn player), and Lily 10 (not yet a horn player).

Ann Drinan: Tell me a bit about the TSO musicians. Where do they live, how much do they earn?

Alan Taplin: We have 48 in our core orchestra, with a base salary of $25,707. Lots of people negotiate their own salaries, however; most musicians make more than the base salary. It’s hard to tell how much discretionary money is in the contractual payments – most get at least 5% more, and many get much, much more.

We started the core about 30 years ago to attract more musicians to Toledo. In the first few years, the Principal players got enormous contracts. Most of them are gone now through attrition. The musicians are pretty comfortable with each other – most of those not in the core do not aspire to be in the core, because they have day jobs or other interests.

90% of the players live in Toledo – there’s only a handful left who don’t. We don’t pay mileage any more, so that’s another incentive to live in town. I used to commute down from Ann Arbor – back then the TSO didn’t pay enough for me to make a full-time commitment. Now they do and I’ve moved to Toledo; I teach at a few local universities in addition to playing with the orchestra.

Basically we’re in good shape. Next year will be challenging because the Mellon money is going away and we’re losing some support from a major foundation, so we’ll have some funding issues.

AD: How do the musicians feel about their colleagues working on the staff?

AT: There’s a little bit of distrust with some players, especially with the new players; they’re often surprised to find their colleagues working on staff. The long timers generally don’t have a problem with it. It’s hard to find a second job that works around our symphony schedule, so working on staff is a good source of income for some players. They’re not pro-management per se and they’re not managers either.

AD: What did the musicians think about the TSO’s involvement in the Mellon Orchestra Forum initiative?

AT: There was a wide variety of feeling, from distrust to positive thoughts. We sent several musicians to the forums and they came back generally impressed. We have good communication with our board and management in Toledo – Mellon was trying to get across how to communicate better, so there was nothing earth shattering about it for us, as we’re already communicating quite well.

The extra money for the orchestra was great. The personal grants were very helpful and appreciated. I received an individual grant to purchase some software to use for my arrangements. To sum it up, I’d say participating in Mellon didn’t have a huge impact on us except for the individual grants.

AD: Tell me about all the neighborhood concerts you do.

AT: The players are generally happy with the idea, though we do about 20 in December, which can get to be a bit much. And the work load can be strenuous. Some venues request specific repertoire around a theme – we can have 50 pieces to prepare – ready to go – simultaneously. It would be better with a bit more rehearsal and prep time.

Sometimes a church will want us to perform with one of their soloists – this can sometimes be an issue in terms of the quality of the soloist. It’s been getting better lately. Chelsea Tipton, our Associate Conductor, does most of these concerts; he and Merwin [Siu] work pretty closely with the venues to plan them out.

Toledo is unusual in that we have a Principal Conductor and Resident Conductor, but no Music Director – sometimes it feels like too many cooks but no head chef. Occasionally I think there are too many people dealing with programming, with no one ultimately in charge. It seems to lurch along at times, and is not as efficient as it could be. But these concerts put extra money in our pockets and give us a chance to perform solos and concerti.

AD: How are your negotiations?

AT: The last time was pretty painless. We got a decent contract without too much trouble. We had some trouble 30 years ago, around the formation of the core, but once we got up and rolling, things settled down. Everything has become easier as the orchestra grew up. Bob {Bell] has been fine to work with for the last 25 years. He truly cares about the players – it’s been a very positive relationship. Even in the hard times, we knew he wouldn’t cut us off or let us go. But then he was our Principal Timpanist for many years, so he knows what it’s like to be one of the musicians.

Interview with Richard Anderson, Board Member

Ann Drinan: How did you get involved with the TSO?

Dick Anderson: I’m not a musician but rather am a businessman. My father, my four brothers and I started our business, The Andersons, Inc., 61 years ago. I’ve been very involved in the community at many levels for many years. It was very easy for me to identify with Bob Bell because of the philosophy he has utilized in running the TSO. He attempted for many years to get me involved with the symphony board.

15 to 20 years ago they were talking about turning the orchestra into a chamber orchestra because they’d run out of funds, and they asked me to join the board as Chair of the Development Committee. I made a commitment that I would try to keep the orchestra intact, so we went to work and contacted individuals who had supported the orchestra in the past. We were able to bring people together and build an endowment that’s now approaching $20 million. We’ve been balancing our budgets – we’ve had a few deficits over the years but we’re working hard. Our ten-year financial plan is a tough one – we’ve fallen behind on it, but we’re working together hard on it.

I really respect Bob [Bell] and how much he cares. I have personal relationships with a lot of the musicians – their lives are so different from mine. It’s fascinating to me, the way they approach life and what they provide to the community. The roots of my interest stem from my mother’s love of music – I went to concerts as a teenager, and we had a neighbor from a musical family who really inspired me.

The orchestra receives wonderful support from the community – they really care. As our artistic product improved, a wonderful group of musicians made their home here. We’ve formed a great relationship with the community.

AD: Were you involved with the Mellon Orchestra Forum?

DA: I spent a lot of time on the Mellon project, and think we were chosen because of the steps we had already taken. Mellon brought musicians, board and staff together – all the stakeholders – to talk about a variety of issues: how to survive and to become better both artistically and financially.

It made me realize the importance of the relationship with the musicians, particularly seeing the problems other orchestras were having – a lack of positive collaboration between the key constituencies. If you don’t work as one team, focusing on the same objective, it’s hard to succeed; you’ll have discord and then that becomes the agenda. Cooperation must become a lifestyle but you can’t do it overnight.

Mellon also provided the funds to let musicians put a project together from start to finish. The Mellon funds really let our musicians express themselves and stretch themselves.

AD: What is the TSO’s role in the community?

DA: The TSO presents wonderful concerts in a lot of different formats and venues. We have our core Classic series but we also go out into the neighborhoods and regions – the communities really appreciate these concerts because they’re fun concerts to attend.

It takes some promotion to pull them off. My parish presents one every other year. It’s a big effort: the church needs to find sponsors to pay the orchestra, sell tickets, line up volunteers, etc. But the neighborhood concerts are really important to spread the word about the orchestra.

AD: What is the financial health of the orchestra?

DA: It’s a difficult time right now; every orchestra is struggling with it. But we have real musician participation in the discussions – they serve on the Executive Committee, the Finance Committee, and our Orchestra Relations committee meets regularly with the Orchestra Committee. We make a real effort to get all the issues out in the open.

My message is: transparency, honesty, trust, patience, and cooperation. Most of our musicians believe in that also. Collaboration has to be real, and you have to work at staying positive. The fact that my home town has an orchestra like the TSO is fantastic!