Issue No. 6: April, 1998

Publisher’s Notes by Paul R. Judy

Institute Activities During 1997

Symphony Orchestra Institute: Organization Change Consultation

Research Update

The Jurassic Symphony: An Analytic Essay on the Prospects of Symphony Orchestra Survivalby Robert S. Spich and Robert M. Sylvester

Restoring the Ecosystem of American Classical Music through Audience Empowerment by Sung Fu-Yuan

The Leadership Complexity of Symphony Orchestra Organizations by Paul R. Judy

Special Section: Women in Leadership Roles

Women Conductors: Has the Train Left the Station? by Marietta Nien-hwa Cheng

A Quantitative Analysis of Women in Leadership Roles in Symphony Orchestra Organizations

Gender and Leadership: A Review of Pertinent Research

Book Review by Mary Parker Follett

About the Cover…by Phillip Huscher

Publisher’s Notes

We open this sixth issue of Harmony with a report of the Institute’s activities during 1997, our second calendar year of operation. As you will see, we are steadfastly pursuing our mission of fostering positive change and organizational development within North American symphony orchestra organizations.

As leaders within symphony institutions become more interested in improving the cohesiveness and effectiveness of their organizations, and building greater enthusiasm, trust, and good will, they will be increasingly open to examining their internal structures and processes. There is evidence that such introspection is already under way in some organizations. As this pattern acquires momentum, forward-looking leaders will wish to consider “organization change programs” utilizing “process consultation.” Indeed, the Institute is interested in selectively sponsoring such efforts. The Institute has adopted a statement of beliefs and principles which it proposes should govern organization change and process consultation programs (page xi). For all participants in symphony organizations, we urge a careful reading of this statement, and welcome any thoughts and questions.

In May 1997, I attended a conference on the cultural industries sponsored by New York University’s Stern School of Business. Many interesting papers were presented at that conference, including a thoughtful study by a West Coast professorial team. Robert Sylvester, the new dean of the School of Fine and Performing Arts at Portland State University in Oregon, has had a long career as a celebrated cellist, festival producer, and educator. He has a deep love for the arts, particularly music, and the symphonic art form. Robert Spich is an associate professor in organization and strategy at the Anderson School at UCLA. Joining their diverse training and perspectives in a respectful but detached way, and drawing from their Stern conference presentation and subsequent work, they have authored for the Harmony audience a longer-term perspective of the symphony orchestra institution within the framework of “organizational ecology.” As you will see, they raise a number of issues as to the very survival of symphonic institutions, particularly those which do not identify and pursue effective adaptive strategies. In a subsequent issue of Harmony, the authors will put forth a range of strategic choices which they believe these institutions should consider in order to preserve their institutional standing, and carry the symphonic art form forward into future generations.

Thoughtful people generally agree that the symphonic art form needs regularly to be energized with new music if it is to retain its vitality and expand its following.

What music is to be selected for orchestra performance, and through what decision-making processes selections are to be made, tend to be the issues. These matters have been addressed directly and obliquely by various authors in previous issues of Harmony. In this issue, Soong Fu-Yuan takes the position that audiences, as well as performers, should be substantially more involved in the encouragement and selection of new music. This involvement should be actively promoted by adapting methods well established for introducing many other new consumer products and services in a pluralistic, democratic, capitalistic society. New music should be nominated and played by performers before voting audiences, and composers should be rewarded handsomely if their music receives the highest public acclaim. Fu-Yuan’s view is that audiences should be “empowered”—invited to be much more alert, actively involved, and trusted in their choices of what new music is to be played for them.

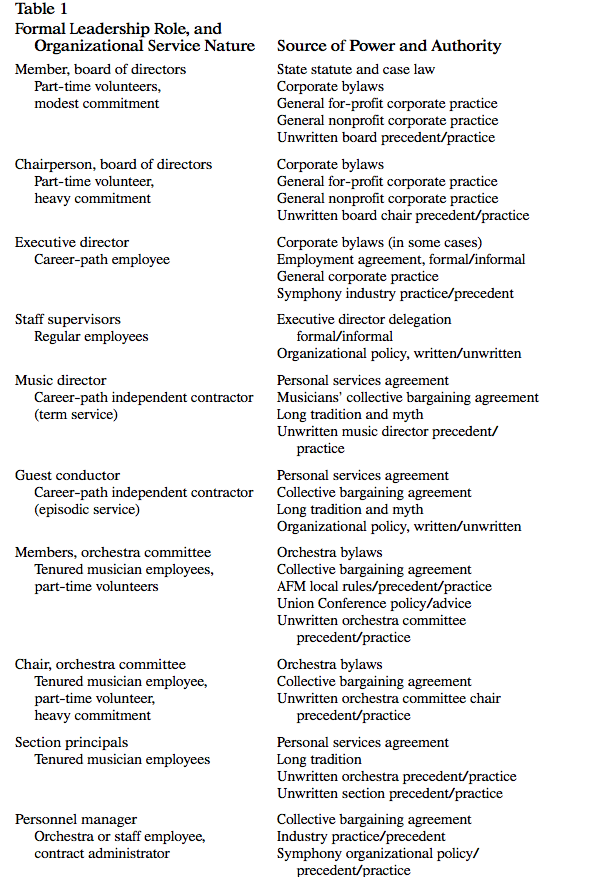

Since the formation of the Institute, we have regularly propounded the unique makeup of the symphony orchestra organization as compared with any other organizational form. In organizational science terms, symphony organizations are “complex systems.” Through regular discussions with leaders throughout many organizations and by standing back and analyzing what I hear and observe, I have concluded that these systems have a “leadership complexity” which is in itself unique. Further, I believe that this complexity in formal leadership roles is a contributor to generic institutional complexity, as much as it is a result. I lay out these observations and their implications as to organizational process and functioning in an essay starting on page 41.

When one becomes deeply involved with symphony organizations, especially with the idea of better understanding their leadership complexity, it becomes quickly apparent how many leadership positions women occupy. We decided to explore this aspect of the symphony organization world in a series of interviews, reports, and essays brought together in a special section: “Women in Leadership Roles in Symphony Orchestra Organizations” that begins on page 45.

The initial content of this special section consists of reports of interviews and roundtable discussions with three separate groups of women in common leadership roles in symphony organizations. We are indebted to Marilyn Scholl, Sara Austin, and Margareth Owens for their excellent editorial work in collecting and preparing these reports. And, special thanks, also, go to each of the 17 par- ticipating leaders!

These reports are followed by the very personal and lively insights of Marietta Cheng about the challenges of being a woman music director and conductor, and her views about the glass ceiling which exists in her profession.

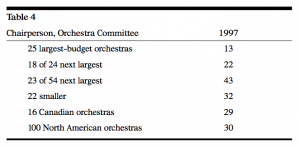

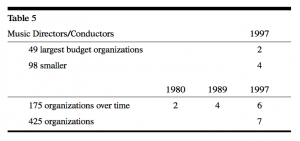

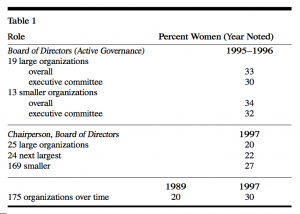

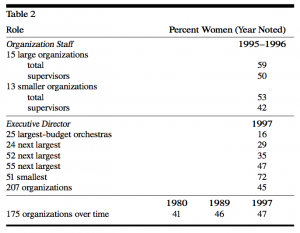

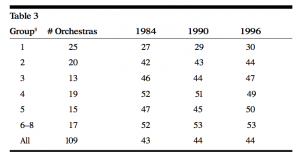

Following this essay is an analysis we have compiled as to the level of participation of women in various components within symphony organizations, and in leadership roles. We think you will find this data quite informative, if not striking.

To round out this special section, we present a review of scholarly research on the topic of sex differences, especially as relates to organizational leadership patterns. In a neighboring Evanston institution, we were pleased to find Alice Eagly, a well-known scholar in this area. In interview format, Alice reports her research findings, and comments on various aspects of gender and leadership in the world of symphony organizations.

Mary Parker Follett was one of the most profound thinkers on the topic of organizational leadership. Writing and speaking in the 1920s, her ideas were well ahead of the times. Although certainly respected by a number of practicing managers and by some contemporary scholars in organizational behavior, her thoughts and writings were generally forgotten. Martha Babcock, a musician leader in the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a scholar/writer in her own right, presents an impressive review of Follett’s writings, recently republished in a volume entitled Mary Parker Follett—Prophet of Management: A Celebration of Writings. We think this review may well send many of our readers to the nearest bookstore. You have probably already noted that the bookmark accompanying this issue highlights a Follett quote!

Pictured on this issue’s cover is a fragment from the score of a truly fantastic piece of orchestral music. Can you identify it? From the perspective of historical orchestral development, why was this music so special? On page 116, you can verify or discover the answer in the excellent vignette prepared by Phillip Huscher.

We are grateful to the 35 symphony organizations listed on page 118 for their 1998 “early bird” support of the Institute. The list includes 18 organizations providing support for the first time. Our goal for supporting organizations by year end is 100. We have a long way to go, renewing the support of some 40 organizations and adding at least 25 new supporters. If your organization was a 1997 supporter and has not yet renewed, or if your organization has not yet initiated support, may we have your help in achieving our goal? Levels of suggested support are listed on page 121, but each organization is free to con- tribute what it believes is merited, either more or less than the suggested level. Thanks!

As noted in the report of 1997 activities, the Board of Directors believes that the Institute should become open to broad financial support by individuals— those who participate as volunteers and employees in symphony organizations served by the Institute, and those who are otherwise particularly interested in the well-being of symphony organizations. To that end, an envelope has been inserted in this issue for the convenience of those who wish to support the aims and programs of the Institute. A contribution of any size will be a vote of confidence in our endeavors.

Institute Activities During 1997

In our second calendar year of operation, the Institute accomplished a great deal!

On the research front, we published Arthur Brooks’ doctoral research findings as the first of the Research Studies Series under the title: “Improving the Orchestra’s Revenue Position: Practical Tactics and General Strategies.” Dr. John Breda completed the collection of data relating to musicians’ psychological distress in the orchestral workplace and, with Dr. Leonard Doerfler, is developing findings which should be disseminated in 1998. With the consent of the International Conference of Symphony and Orchestra Musicians, the Institute began an analysis of conductor evaluation data provided by ICSOM orchestra players over the last decade. This analysis will determine what insights and conclusions might be available from such data. Other proposed research projects were being evaluated as of year end.

In our publishing program, beyond the Brooks research study, the spring and fall issues of Harmony were met with enthusiasm. These issues’ content filled more than 200 pages and included 14 separate essays or reports by 12 authors, and contributions from more than 20 other industry participants or close observers. Some 12,000 copies of these issues were distributed to employees and volunteers in symphony organizations—more than 6,000 copies to board members, other volunteers, and staff employees, and the balance to orchestra players. Copies were distributed to approximately 1,500 individuals in academic institutions, symphony and other related trade and service associations, media organizations, charitable foundations, government arts agencies, and various business and professional groups.

In early summer 1997, under the sponsorship of the Institute, and working cooperatively with leaders and other participants of an important Midwest symphony organization, a professor trained in organization analysis and change interviewed many individuals and observed a number of group meetings to learn how the organization was structured and functioning. With the benefit of this experience, the Institute moved forward with its “ODR” program, placing a few highly selected academic scholars or teams specializing in “organization development” in “residency” with a few highly selected symphony organizations. Two residencies were under way as of year end. The primary goal of the ODR program is to permit resident academics to observe and learn firsthand how a particular symphony institution is organized and functioning, and, through reading, discussion, networking, and the application of general organizational theory and experience, to identify and illuminate generic organizational patterns and processes being followed in North American symphony organizations, and to determine how these patterns and processes impact institutional effectiveness.

As the year closed, the Institute was also exploring the possibility of sponsoring facilitated change programs within selected organizations. Over time, it is expected that various organizational observation and consultation projects will help the Institute develop methodologies of organizational analysis and change which can be adapted to specific organizational settings, disseminated broadly, and which can contribute generally to improved organizational effectiveness.

In January 1997, the Institute established a small office in Evanston, Illinois. By year end, operations were settled in, records and files organized, and publications stored. In late October, the Institute completed a Web site with the Internet address of www.soi.org. Extensive background information about the Institute has been posted there, including the primary content of the first three issues of Harmony and the complete and regularly updated bibliography of writings and research about symphony orchestra organizations.

Early in 1997, the Institute reorganized its founding governance structure by formalizing two boards: a Board of Advisors and a Board of Directors.

◆ The Institute’s Board of Directors has the legal obligation to oversee the direction and operation of the Institute and its longer-term devel- opment and strength, including management succession. During the year, the Board of Directors had three meetings, two formal and one informal. The group was quite supportive as the year progressed and programs took shape. As of year end, the members of the Board of Directors were Frederick Zenone, Richard Thomas, Henry Fogel, Debra Levin, Paul Boulian (newly elected), and myself. Biographical informa- tion about these board members is available at the Institute’s Web site.

◆ Early in the year, the Institute organized a Board of Advisors, with a membership of up to 15. This board was established to gather advice and counsel from a group of persons reflecting diverse role, organiza- tion size, gender, and geographic representation of North American symphony organization participants. Above all, persons invited to be advisors are dedicated to the aims of the Institute and supportive of its efforts in all circles. Thirteen members were appointed as of year end, including Ann Drinan, Paul Ganson, Joseph Goodell, Sara Harmelink, Joan Horan, Libby Larsen, Bob McPhee, William Moyer, Ward Smith, Stephen Stamas, S. Frederick Starr, Gideon Toeplitz, and Hugh Wolff. Biographical sketches of these advisors are also available at the Institute’s Web site. During the year, each advisor has been available for counsel and has been supportive of the Institute’s goals. The Insti- tute is warmly appreciative of the interest and commitment of each advisor.

As the year progressed, many symphony organizations initiated support of Institute aims and programs. At the end of 1996, 17 institutions were supporting the Institute; by the end of 1997, this number had grown to 55. For 1998, we have set a goal of at least 100 supporting institutions.

At its December 1997 meeting, the Board of Directors decided that the Institute should become broadly open to financial contributions by individuals who wish to support its goals and programs. For the convenience of those who wish to provide their support, a mailing envelope is enclosed. Warmest thanks in advance for such encouragement!

We welcome your questions and comments, and your support!

Paul Judy March 1998

Symphony Orchestra Institute Organization Change Consultation

The mission of the Symphony Orchestra Institute is to improve the effectiveness of symphony orchestra organizations. In many organizations, such improvement will require significant change in the way the organization functions—significant change in internal processes and interactions.

In pursuing such change, an organization will quite often seek professional assistance from an “organization development” consultant or team. Indeed, the Institute may wish to assist selected, interested organizations in identifying and engaging consultants. The Institute may also wish to sponsor or assist some “organization process consultations,” including participation in the funding requirements. The Institute would participate, in part, with the view to developing more institutionalized methodologies which can be adapted to the specific needs of individual symphony organizations.

To this end, the Institute has adopted a set of beliefs and principles to guide “organization change” projects and consultations in the symphony world. The Institute hopes that the following statement of beliefs and principles will assist symphony organizations and consultants to pursue sound organization change programs. This statement is a charter for any consultation projects with which the Institute becomes affiliated.

Institute Beliefs and Principles

Total Systems Approach

The Institute believes that the most effective “help” or support to a symphony organization will occur when the process takes a “total systems” view. All groups within the “organizational system,” including the board, other key volunteers, staff, music director, musicians, their union, and parties representing audiences, general contributors, and the community at large, must be involved in some appropriate way in the process. Thus, the client in any organization change consultation must be the whole system. Every participant and related group involved in the organization must be served, directly or indirectly, as a whole, in an open and honest way.

Common Purpose and Vision

The most effective change for a symphony organization will come about when key leaders of each organizational component are aligned and supportive of a common, shared purpose and vision. The consultant must create processes and systems which encourage a common, shared purpose and vision, and a reconciliation of views when required.

Securing Will and Commitment

Sometimes consultation is required to secure the will and commitment of all parties essential to achieving a common, shared purpose and vision. The consultant may need to work with groups sequentially if this is required to secure the will and commitment of all key parties.

Freedom to Participate

Freedom to participate is key to high levels of involvement in organization change processes, and their eventual success. Those involved in symphony organization improvement processes must participate voluntarily, and have the freedom to withdraw from involvement at any time. The consultant must create processes which always establish conditions for the exercise of free will, but with an under- standing and appreciation of the consequences of the exercise of that will.

Nature of Interaction

Individuals will bring to discussions their biases, history, and concerns as a normal part of working through issues and alternatives. The consultant must develop processes which account for and permit the expression of all points of view and opinion by all participants and groups, but emphasize the importance of engaging one another in a constructive, positive way. The consultant must also develop processes which ultimately will encourage open, frank conversation and appreciative listening.

Procedural Guidelines

Shared principles of behavior are key to civil, constructive, positive interaction among people working together to bring about change. The consultant must help the parties develop shared principles to guide behavior.

Nonalignment

The Institute believes that consultation will fail when and if it is viewed by one party as a means for validating or confirming a position, decision, or action of another party. All consultation must therefore be pursued with clear nonalignment, and be dedicated to finding a reconciliation of views and supporting the agreed-upon actions of all parties.

Recognition of Legitimacy

The symphony system is comprised of a number of different constituencies, each of which has a legitimate and important point of view and perspective that requires representation in any effective change process. The consultant must develop and support processes which maintain the legitimacy of all constituencies and which will not, through design or intent, denigrate or undermine the position of particular constituencies, individuals, or their points of view.

The Role of History

History is important in understanding the roots of current thinking and behavior, and must be recognized for its contribution to the present. The consultant must utilize history as a learning tool to help all parties understand how to improve current thinking and behavior.

Length of Engagement

What has taken years to establish cannot be undone overnight. The consultant must be engaged for a period sufficient to create a process which is perceived to have long-term impact along with immediate satisfaction of specific issues and concerns. The engagement must be sufficient to generate the energy and momentum which will lead to longer-term success.

Self-sustaining Process

Long-term success of any change program requires that the organization develop its own internal resource and support capability for continuous improvement. The consultant must help develop this capability in designated parties and help design appropriate supporting processes so that positive organization change will become self-sustaining.

Organizational Capability

The greater the interpersonal capability of all participants in an organization, especially those in current and prospective leadership roles, the greater the chance that organizational improvements will be sustainable. One objective in the design and execution of any intervention process should therefore be to develop the capability of all participants, and especially leaders, to work more effectively together.

Tangible Support

The chances of success increase when the investment required in a change process is shared equitably by all participants and groups involved. Every effort should be made to create the highest level of shared tangible investment on the part of all key parties, including monetary investment and other investments of time, energy, thought, commitment, and reputation.

Multiple Resources

Symphony orchestra organizational change consultations will usually be relatively complex, multiparty engagements, potentially involving board members, other key volunteers, staff members, the music director, player committee members and other musicians, including representatives of the local union, and perhaps some community representatives. In such engagements, it is often more effective to have multiple resources involved in the engagement and wherever and whenever possible, to utilize such multiple resources in designing and engaging in the intervention.

Research Update

Research Update

Organization Study

In the October 1996 issue of Harmony, the Institute reported that it was developing an “OD-in-residence” program, in which an “organization change” scholar (perhaps joined by a graduate student) would spend a number of days, over a period of months, with a symphony organization, observing various group meetings; completing interviews with many of the organization’s participants—personally and in small groups; studying written material developed within the organization; attending rehearsals, concerts, and other group services and events; and obtaining insights from community leaders about the symphony organization and the local environment.

During this process, the resident scholars would become familiar with the values, beliefs, and goals existing within the organization, as well as with organizational structure and functioning, and with decision-making and communications processes. In addition, the scholars would be absorbing background material about the industry and its environment, and exchanging views with each other. Each residency is intended to foster organizational learning—an appreciation shared by many participants of how the organization is functioning, what is working well, and what issues and challenges the organization faces.

Toward the end of 1997, the Institute established a residency program with two collaborating symphony organizations. We anticipate that these residencies will be completed by midyear. The Institute may initiate other residencies in the fall.

Organization Change Consultation

In addition, the Institute is pursuing the sponsorship of one or more programs of organization change involving process consultation, and has adopted a statement of beliefs and principles to guide these programs (see page xi). As noted in the preamble to this statement, the Institute is intent on developing methodologies for organization change in symphony institutions that can be adapted to the needs and circumstances of specific organizations.

Conductor Evaluation Data Analysis

In another direction, with the consent of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians (ICSOM), the Institute is undertaking an analysis of conductor evaluation data created by ICSOM orchestra players over the last decade, and maintained at Wayne State University. The goal is to determine what, if anything, such data might reveal about various dimensions of orchestra conducting, from the point of view of orchestra players.

Other Projects

The Institute maintains regular contact with a number of scholars pursuing various research projects relating to symphony orchestra organizations.

Extending the Bibliography

Prior issues of Harmony have contained either cumulative or incremental additions to the Institute’s bibliography on the literature of symphony orchestra organizations since 1960. The entire, updated bibliography may now be found on our web site at:

www.soi.org

The Jurassic Symphony:An Analytic Essay on the Prospects of Symphony Orchestra Survivalby Robert S. Spich and Robert M. Sylvester

EDITOR’S DIGEST

The Jurassic Symphony: An Analytic Essay on the Prospects of Symphony Orchestra Survival

Ecologists study the interactions, relationships, and patterns of settlement of living organisms within their environmental settings. Organizational ecologists study similar interactions among organizations and their environments, using social, economic, and political yardsticks as their tools of measurement.

In a skillfully written essay, authors Robert Spich and Robert Sylvester take readers on a fascinating ecological tour. Robert Spich brings to this essay the perspective of a professor of management and international business; Robert Sylvester brings that of a professional musician and arts administrator.

Tracking the Decline

The essay begins with a discussion of the symptoms of decline in symphony organizations. The authors enumerate what they observe as suspected factors. They then establish a Darwinian ecological metaphor (Jurassic), and a set of ecological assumptions to guide readers through eight ecological propositions applied to symphony organizations.

The Broccoli Problem and Cadillacs

Lest readers think that this essay might be a “tough read,” it assuredly is not. Authors Spich and Sylvester are very capable of tucking their tongues in their professorial cheeks as they select examples to explain serious economic concepts. Using such comparatives as a “broccoli problem” to describe free choice, and a “Cadillac problem” to assure readers that symphony organizations are not alone in experiencing decline, the authors outline thoroughly the current ecology of American symphonies.

This essay is the first in a two-part offering from the West Coast writing team. In a subsequent essay, they will explore a range of strategic choices which symphony organizations have as they fight for survival.

The Jurassic Symphony: An Analytic Essay on the Prospects of Symphony Orchestra Survival

The history of classical music and of the symphony institution describe well the conditions that gave rise to the symphonic musical form. This historical record is less informative about how the fundamentals of the environment and societal culture have impacted, and continue to impact, the symphony orchestra as an organization. In this and a subsequent essay, we hope to contribute to this long history by framing the symphony orchestra’s issues within an organizational science perspective that becomes a basis for managerial action. Specifically, this essay applies an organization ecology analysis to the symphony orchestra community. The ecological perspective focuses on the larger processes of organization- environment dynamics which affect how organizations start, grow, mature, and decline. This perspective seeks to explain how environmental forces help shape the conditions for success or failure of an organization. In a subsequent essay, we will utilize a strategic management framework to focus on how management might address faltering performance and seek to identify realistic options and choices for continued success. Jointly these two organizational perspectives frame the larger problem plot: how organizations can become “de-fitted” from their environments and, in the absence of strategic change, face the probability of decline and failure.

We are hopeful that good music will go on forever, and that people, given the opportunity, will always choose music making over the drudgery of labor. We laud such sane human tendencies. However, we have two nagging concerns: the sophisticated art of the classical musical genre, if it becomes extinct, would not be shared, enjoyed, and cherished by many future generations, and the role which serious and traditional music has had in “civilizing” a society might become irrelevant or lost. In each case, it is not clear what the substitutes might be. For these reasons, the continuation of the symphony orchestra as a vehicle for the intergenerational transmission of musical culture and the development of a civil society should be an issue of wide concern. For the symphony orchestra to remain a major cultural carrier, it must concurrently be an institution “of the past” and “of the future.” The trick is a fit to the times, with tradition, but go toe to toe with contemporary trends. Let us now begin to look at what makes that trick so difficult.

Symptoms of Decline

In any society, the rise and fall of organizations is a fact of organizational life. History itself records similar fates for civilizations, but history does not explain decline directly. The causality is never clear or unambiguous. Rather, as in the rise and fall of Rome, decline theory is a descriptive exercise in which one cites the factors at play during a time period and tries to draw inferences on how those factors contributed to declining performance of a system and its eventual failure. For the symphony organization, a list of suspected factors follow.

- Increased amounts of extra-industry competition for time and attention from easily accessible substitute cultural and technology products.

- Audience aging (shrinkage) and difficult recruitment from younger cohorts.

- Decline in music education budgets and programs in schools, creating a loss of music appreciation and skilled listening discipline needed for audience development and attendance (e.g., theme of the recent popular movie Mr. Holland’s Opus)

- Increased forms and sources of intra-industry competition: location and venue competition; inter-period competition where older rereleased recordings of past masters compete with new interpretations; alternative formats and orchestrations of classical music versus standards; competition between periods (Baroque vs. Romantic); special use after product competing with original intentions (e.g., Mozart for improved learning).

- Market saturation and listener exhaustion through overabundance of musical product in the market and on the airwaves, forcing more and more exaggerated differentiation strategies to gain attention.

- Increased competition for scarce resources from a hostile and stingy public and private donor environment.

- Time pressures and lifestyle stress issues curtailing audience attendance, changing ways in which people use music in their lives (e.g., the ease of listening to a CD rather than the hassle of going to a concert).

- Unequal regional and urban economic development, creating differentials in economic bases of support for the arts (e.g., one city builds a new symphony hall while another lets its hall go unused or be closed down).

- Multiculturalism and diversity pressures for alternative ethnic traditions in music.

- A conservative political climate with leanings against “elite” art projects and government spending.

- Widespread decline of general education standards and performance, affecting the appreciation of the role aesthetics play in the quality of everyday life through the willingness to support artistic activities without practical payoffs or immediate relevance.

- The dominance of “pop” culture in everyday life with an emphasis on consumerism, mass commercialization, and the “mcdonaldization” of individual choice in contemporary society (i.e., everything is for sale, now, quick, cheap, instantly gratifying; everything and everyone has a price, and all is ultimately disposable).

- The apparent contradiction in a democracy between “good taste” and connoisseurship in favor of eclecticism, and inclusion or embracement without judgment or criticism.

These factors—over time, and both directly and indirectly—tend to exacerbate ongoing organizational issues and often overwhelm them with the menagerie of problems. These factors are what ecologists might term “fundamental environmental conditions” which help shape the decision paths that organizations need to take. In most cases, the factors cited exist on a grand societal scale. This means that they are usually part of a longer-term historical evolution of society, the results of various trends and developments, some of which are recognizable and transparent, others of which are hidden in the forces of history and only seen in ex-post analysis. Some factors can be influenced, deflected, or contained by various efforts; others, such as technological innovation, audience aging, the commercialization ethos, and changing contemporary lifestyles, are fundamental and comprehensive. They have large- scale, noncontrollable effects which create a critical decision context for the orchestra management. As we will discuss in our second essay, you can fight them head on, you can steer around them, you can make adjustments to them, but you cannot get rid of them. The trick is to find ingenious ways, whenever possible, to turn them to some advantage, but that is for later discussion.

On a more specific basis, events in the 1996-1997 season alone show some of the more recent symptoms of difficulties and portents of decline that changing environments cause:

- Musicians’ strikes at the venerable Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as in San Francisco, Atlanta, and Portland.

- Politicized confrontations between musicians and management, as in the recent Seattle Fifth Avenue Theater case.1

- Closure, bankruptcy, or near bankruptcy in the San Diego, Sacramento, and Charlotte symphony organizations, respectively.

- The surprise announcement of a possible and portentous merger of the Vancouver Symphony with the Vancouver Opera in 1997, followed by the merger’s cancellation.

- The decline of the market share of classical music from 7 percent in 1987 to about 2.9 percent in 1996.2

- The rise of more contentious issues in nego- tiations, such as classical recording royalties, industry standards for job security, core orchestra size, and the use of medical leave.

- Acknowledgments by management and musicians that “the cuts in arts funding and music education have had a serious, negative effect on the health of symphonic institutions across the continent.”3

A relatively clear record of symphony orchestra failures over the last decade provides perhaps the last corroborating evidence of a decline, as can be seen in the cases of Oakland (1986), Oklahoma (1988), Denver (1989), New Orleans (1991), Florida (1993), Alabama (1993), San Diego (1996), and Sacramento (1996).

Organizational declines and failures such as these can be viewed from two perspectives: external and internal. One can identify a host of factors outside an organization which will explain an organization’s demise. However, looking only at external explanations allows for blame to be placed on “devil” theories, creates passive/reactive scenarios, and provides only selective and incomplete descriptions of reality. More commonly, organizational performance, both good and bad, can be explained from an internal perspective which looks at how well the organization’s leadership understood strategic problems, focused efforts, picked goals, designed appropriate operations, rallied organizational commitment, and addressed opportunities. From this viewpoint, organizational failures result from acts of commission or omission by people who miscalculate, have faulty perceptions, or make blundering errors. Given capitalism’s demands for successful economic performance and a bias toward action, such performance judgments in the for- profit world are often harsh and unforgiving. While business criteria might not be relevant in analyzing cultural organizations, the focus on an organization’s leadership is. Any explanation of a symphony organization’s failure requires both perspectives.

In contrast, explaining the failure of any individual symphony orchestra without glib generalizations requires an in-depth analysis of the internal workings of that organization. Consultant case studies, such as the one done on the demise of the Oakland Symphony,4 provide a rich array of detail which allows a “reconstruction” of the story and the learning of certain lessons about poor decisions and actions. However, individual case studies are unique situations which may not allow easy generalization and may be wrong in their analyses. As for future lessons, one can always dismiss the case situation that does not specifically or favorably reflect on an individual organization’s present situation and problems. For these reasons, it is often better to use a theoretical framework, such as organizational ecology, to help explain the basic forces that may be driving an industry.

An Ecological Metaphor

An ecological perspective on symphony orchestras was inspired, in part, by a drawing that appeared in the arts section of the New York Times.5 The drawing shows an upright conductor, dressed in tails, baton poised, body arched and hands steadied, signaling the orchestra for the imminent downbeat and start of yet another great moment of classical music. While this image is perhaps the most expected symbolic icon of the whole genre of classical music, the background, in the form of a paleontological metaphor, is the more telling message. For behind the conductor appears a Jurassic scene, where dinosaurs stride freely, but often uneasily. On the left, a huge, slow-moving, seemingly content, and perhaps unaware brontosaurus feeds on the abundant greens in a large lake whose shallow, but decreasing, depth is enough to keep the lurking and hunting carnivorous tyrannosaurus on the shore poised, waiting, but still at a safe distance for now. At the same time, sharing the air with a lone pterodactyl, are what at first appear to be strange, asynchronous portents of the future—flying saucers! However, upon closer examination, these discs in flight represent no less threatening an image than symphonic sound in flight, transmitted by the carrier—the CD recording.

The point is poignant and unambiguous: symphonies may share the fate of dinosaurs and CDs may be one of the factors contributing to their demise. The implicit message is that symphonies cannot keep doing what they are doing and expect things to continue unchanged and forever. The risk is the fate of the dinosaur—an extinct species, unaware of the larger forces of decline at work that determined its destiny, still a fascinating beast, but essentially dead!

The science of ecology is the study of interactions, relationships, and patterns of settlement of a group of “living things” within an environmental setting. If one looks at a pond in the woods, the ecologically curious mind wants to understand how things got that way: Why these trees? Why these flowers?

Why these animals? How do they “live and die” together? Organizational ecology (OE) wants to know similar things: Why are these kinds of organizations here? What are their life cycles? How do they interact? What are the important webs of relationships? What determines success or failure of a group? Organizational ecologists “seek to explain how social, economic, and political conditions affect the relative abundance and diversity of organizations and attempt to account for their changing composition over time.”6 Thus, OE begins with fundamental observations:

- There is diversity of organizations in any grouping of organizations as we see in the classical music community.

- Environments often change more rapidly than the organization’s ability to keep up with the changes, thus implying failure and disappearance of an organizational form.

- A community (industry) of organizations is rarely stable because organizations continually arise and disappear, something we see happening in the symphonic organization population.

- With these basic observations, we begin the discussion with some initial ecological assumptions.

Ecological Assumptions

First, we treat the symphony orchestra as one particular organizational form within the larger classical music industry. The symphony organization includes the orchestra itself and its supportive administrative apparatus. The collection of organizations that share a genre (e.g., all ballet companies) with common activities and patterns of resource needs and uses makes up an organization population. The mix of populations that reside within the same societal environment, but share differentially in the benefits and problems of that environment, represent an organizational community. The classical musical community can be seen as an ecological network of cultural organizations (e.g., opera companies, chamber orchestras, ballet companies, chamber music societies, choruses, concert series organizations, small ensembles) organized around specific musical genres within a “serious/classical music” denomination, and which share an ethos grounded in a love of a traditional musical form and its public presentation. Relationships among these organizations are largely symbiotic, with some direct and indirect competition for resources. Some synergistic opportunities for cooperative action exist both within populations and communities. Within the symphony orchestra population, there is a certain stability based on shared modus operandi, culture, and tradition. For purposes of analysis, the population of symphony orchestras will be treated as the “symphony music industry,” although this conceptualization has a specific meaning in industrial economics. This helps in the articulation and recognition of common “industry-like” problems.

Second, we make a Darwinian assumption that successful music organizations represent successful adaptations to surrounding environments. In the symphony orchestra case, the “organism of study” is a large beast designed to deliver large-scale, relatively long, complex musical works. Presenting these works requires supportive action and organization of similar nature and scale. At the time of its genesis, the symphony orchestra represented the basic truth that the music of a time period reflects the society within which it resides. History seems to indicate clearly that music organization form follows from function, and function follows human motives and purposes. Thus, we see the varied roles that symphonic music played in everyday life, whether to express the nationalistic fervor of the 1800s, to entertain a coterie of music lovers, to impress royalty and assure one’s social status, to provide an outlet for great and ambitious talent, to educate the masses, to please a wealthy patron, to provide background music for larger social and diplomatic functions, or simply to make money for enterprising impresarios. All of these motives and purposes, selfish and otherwise, helped shape the design of the symphony orchestra. Musical forms and products that are appreciated and useful to members of society will be favored for continued environmental selection and survival. The waltz in the masked ball survives to this day because it serves many more private and public interests than simple musical enjoyment suggests.

An ecological analysis with a Darwinian perspective therefore represents a relatively disinterested, objective, and hopefully transparent point of view. Without judging, it merely asks: What is the unit that is making the adaptation? What are the nature and dynamics of the situation to which it is adapting? It then looks at the dynamics of relationship adjustment, the strategies of survival, and the types of accommodations and changes made. Successful adaptation strategies then are measured directly in terms of the quality of the survival strategy. Survivorship is a necessary but insufficient criterion for judging the value of the surviving experience. Highly successful adaptations demonstrate such characteristics as ready expansions of domain, growth in numbers, diversified set of activities and outputs, ready ability to compete with others, high morale, resistance to “disease,” demonstrated ability to use cooperative, as well as competitive, strategies, and other measures of success that indicate a generally healthy organism or organization.

In following a Darwinian argument, we note that adaptation does not imply superiority or constant progress in a form of music organization. It merely suggests accommodation, adjustment, and fit of a sustainable form for that environment. The common notion of “the survival of the fittest” is just that and no more. There is often an implicit meaning that “fitting and surviving” always results in a superior entity. Thus, to say that a newly formed orchestra “fits the audience” probably means that pragmatic accommodations and instrumentation adjustments were made to make a fit work. There is, however, a common progressive assumption about how accumulative improvements lead to “best states.” But that which “fits” does not mean it is the “best ever” or “highest” form attainable. That the coyote can actually survive in dense urban settings— cities—does not mean it is therefore a superior form of animal. It means that among the many animal groups, it has accommodated to the conditions of city life and found ways to survive and even thrive. Similarly, the survival of symphonic “pops” concerts simply points to the fact that this music is “fitting the environment,” or in business terms, “seems to meet a market need.” It does not indicate the direction that all musical organizations should and will go, nor is it a superior judgment about the quality or desirability of the art form.

That organizations survive in dysfunctional conditions, terrible political regimes, and war says both good and bad things about people and their environments. Survival is merely a statement of fact and not necessarily an endorsement for the future. That certain food stores can survive in centers of urban decay does not indicate that everyone, therefore, ought to shop there. That certain orchestras have survived is not necessarily a ringing endorsement for an organization’s repertoire and style of playing. Survivors are just survivors. That they may have engaged in meritorious action just to survive or deserve special recognition is not the point. Whether they serve as models for the future is. When judgments about the quality or value of surviving organizations are raised, the debate moves to, among other, larger questions of taste, aesthetics, and history. While that analysis moves away from the central question of organizational form and its survival, the issue of the real value of a surviving organization remains fundamental in the strategy question.

In the end, a Darwinian viewpoint challenges what may be contradictory purposes: If the symphony orchestra is not a sustainable organizational form for future times, what forms should the symphony orchestra take if it wishes to survive in contemporary times? If it changes form, will it still be a symphony orchestra? If not, does that matter? Just what do environmental forces “select for”—an art form, an organization, both, or something else? Unlike the coyote, which cannot change its form but must look for favorable conditions in already existing environments, the symphony orchestra, being a synthetic human creation, can change form, as well as place, to adapt. It can also influence its environment. What it will do, however, depends on the goals it chooses, and how well strategy is conceived and executed.

Third, the basic unit of analysis is the population (industry) of symphony orchestras which are the dominant form in the larger classical music industry as a whole. The symphony orchestra shares a common genre, generally noted as “classical” (i.e., based in long-term, large-scale, traditional forms, and often defined as serious and “highbrow” music with certain rigorous intellectual and aesthetic standards). The symphony organization is generally differentiated from other music organizational forms in terms of the intensity of organizing effort and expertise that is needed to produce and support that form of music making.

However, even though these organizations are treated as a collective unit of analysis, what is true for the industry as a whole may not be quite as true for any one orchestra organization. On any ecological dimension of interest, individual orchestras will lie on different points of any normal statistical curve. Some are richer than others. Some have more volunteers. Some have more competition. Based on the premise that symphony orchestras tend to share some commonalities of an environment and are interdependent as a population, one can make generalizations—with the standard caveats.

Eight Ecological Propositions

Given the basic ecological observations above, and assuming the relevance of a Darwinian approach to understanding the dynamics of relationships between and among organizations, we can state some general propositions that may help put the symphony orchestra industry’s issues within a sound theoretical perspective.

All organizations go through life cycles with definable stages of initiation, growth, maturity, and decline.7

The American symphony industry is presently at a mature level of development, meaning that a large number of industry members are roughly in the same stabilized situation at the same time in terms of audience, venue, and programmatic growth. This implies that the music product itself has gone through a development process in the form of product-type life cycle (i.e., the symphony) and has settled into some fundamental basic form that is readily recognizable by an audience. The organization that creates and supports this music reflects these cycles in its own growth patterns. Innovations tend to represent improvements as variations on a theme or additions of features to this basic form and its use. Innovations are within products and not substitutions of product, much like brand competition in the supermarket. As a comparative example, the automobile is a stable, mature, known product in which all innovation is in decorative features, convenience, and cost/performance relationships. However, four wheels, a gasoline engine, an enclosed chassis, and a drive train make up the basic unchangeable basic form. Unlike the case of symphony orchestras, there are still no readily acceptable substitutes for the basic individual car. And unlike the automobile, symphony music is a comparative luxury product, subject to discretionary spending decisions. It is not a basic staple or needed purchase.

If this same industry reasoning applies to symphony orchestras, then we can see them as part of a minimally competitive industry where the strategies are still “gentlemanly” and “clubby” in nature. Somewhat reminiscent of the “Big Three” in Detroit, the symphony industry has settled into a mature oligopoly stage where a limited group of known great urban orchestras make up the “big industry players” who provide the bulk of yearly symphonic products. Innovations in orchestra seating (e.g., as in Stokowski’s experiments with orchestra seating to change sound), venue, setting, or programming represent the yearly “model” changes that we see in Detroit. In order to extend their life cycles, orchestras, much like other industries, engage in limited innovations and constant manipulation of the marketing mix—price, product features, and promotion— in order to reach larger markets, sustain share, or build new segments. As in the automobile industry, these actions yield mixed results and do not guarantee survival of any individual firm.

Most industries experience competition from regional, national, and even international players. Some—for example the newspaper industry—are characterized by a few local competitors. Symphony orchestras, however, tend to have monopoly status in which each symphony has a claim to a specific urban environment and there is generally no direct competition in the marketplace. In fact, when on tour to other cities, symphonies make cooperative arrangements to “fill in” rather than compete, in the belief that a variety of orchestra sounds helps sustain market support and growth which benefits all industry members. This may reflect an implicit cooperative survival strategy.

However, as is recognized in strategic game theory, oligopolies tend to have a dilemma.8 Individual organizations can choose to innovate and compete strongly with other industry members or they can go along with general industry practice. If they choose to compete strongly, they risk the possibility that other competing organizations will react either irrationally or with strategies that are costly to match. This leaves every industry member worse off, and the victory in the marketplace is Pyrrhic in nature. However, if the organization chooses not to compete, to forego an innovation or market advantage, it loses the potential individual gains it could have received through larger market share (often at the cost of others). However, by maintaining the status quo, the organization uses fewer resources by only competing on the margin, with small changes and limited innovation. There may be tacit, low-level competition, enough to sustain the industry but perhaps not enough to create important innovations.

Oligopoly-like conditions induce a sense of collective well-being in the status quo, and the perceived need to change becomes minor, marginal, and local at best. This suggests that symphony orchestras, as an industry, may be avoiding innovation and change because they know that the others, sharing a classic culture, will not compete fiercely and that the status quo is an acceptable strategy. However, they forego the possibility of gaining appropriable organizational advantages which might have increased their individual chances of survival. The long-term effect of this cultural conformity is to reduce variation among the population members and to increase their collective vulnerability to sudden changes in the environment. If all behave in the same fashion, they make themselves collectively vulnerable to competition that does not play by the same rules. We note that the U.S. automobile industry shared such false notions of common well-being until the external shock of international competition, playing by very different rules, created havoc in traditional markets. It took 20 years to catch up and adapt to what is essentially a fiercely competitive market now.

Industry homogeneity indicates low rates of innovation and variation of form, and thus, low differentiation between members.

We can readily observe that symphony orchestras are fairly homogeneous in structure, process, and output. In a sense, orchestras are all members of the same species. There is little variation or differentiation of organizational “genetic code” among the symphony “family” members. Ecological theory suggests that variation in form increases the probability that, in the face of challenging conditions, some members will survive to carry on, into the future, important aspects of a traditional organization form.9 With low inter-organizational variation, significant changes in a common socioeconomic environment (e.g., aging audience, low recruitment of new cohorts) then could—assuming conditions hold steady—lead to the increased probability of large-scale simultaneous industry-level downturn and eventual organization failure. Variation, then, is an implicit and unconscious cooperative strategy that spreads the risk of failure among a population of organizations. But if there is resistance to innovation, or if structural/cultural barriers act to prevent change, industry homogeneity, instead of being a proud show of cultural discipline and unwavering tradition, in fact could really indicate an unfavorable state of affairs. If differentiation is a critical strategy for survival, then homogeneous industries face more significant survival problems in turbulent and changing environments.

The resource balance between organizations and environments is a dynamic equilibrium which can be disturbed by purposeful intervention, with both negative and positive consequences.

The argument here states that the “saving actions” by symphony boards and stakeholders may have contributed to a larger than “natural” number of symphony organizations surviving at the maturity stage. Managerial action intervened into “natural” market selection processes, lowered the number of industry exits (failures), and has led to a “bunching” effect at the mature level of the cycle. Assuming that bunching is an abnormal occurrence, a return to a normal probability distribution will send a large number into the next stage, which is decline and probable industry exit.

A conservative observation would cite cause in overly optimistic government programs and foundation support that may have led to an “unnatural” growth of symphony orchestras in the 1960s, more than the “carrying capacity” that a “natural” market environment could bear. The failures of orchestras may really represent an expected natural adjustment process whereby market selection processes are, in effect, “weeding out” the weaker industry members. The effect is to reduce overall numbers and bring back a more “natural balance” with the conditions of the environment. The environment should then be able to support a more reasonable number of participants, and the lives of the survivors will be markedly better off, because there will be more resources for them to share and sustain their activities. This kind of equilibrium thinking is the very basis for policy analysis and decisions in renewable resources industries (e.g., forestry, fishing, agriculture).

In the case of cultural organizations (among others), human intervention into “natural processes” is a basic and constant factor which prevents “natural selections” from occurring easily. Like all analyses of this type, there are assumptions and models that may not fit the case of any one industry perfectly. In fact, such interventions may themselves in fact be considered “natural” under a different set of assumptions and models. However, as a general principle, the balance between resources (the carrying capacity of an environment) and the demand for those resources remains a dynamic-equilibrium phenomenon. This is a silver-lining argument that symphony boards probably know too well and players not well enough!

The relationship between artist and patron audience is symbiotic and functional in the early formation of an organization, but that relationship can become increasingly dysfunctional if it creates barriers to change and adaptation during later cycles of organization development.

We would note here two levels of relationships: that of the patron audience, and that of the single patron who supports a particular artist’s development. With regard to the former, critics have observed that even though mature sectors of the population tend to support the arts at higher rates than the younger population, they are also the ones most resistant to innovation in programming. As one critic put it, “So many subscription evenings read like holding actions: attempts to head off the flight of wary listeners. Almost every orchestra practices the tactic of punishment and reward: a difficult pill followed by an ice cream cone. Distasteful as it is, no professional can avoid this strategy and still survive.”10 The point is, that in order to get the audience to listen to the new music which requires more concentration and is less immediately rewarding, orchestras also must offer a palette of “oldies” that the audience knows, believing that such traditional music is what it really paid for, and that audiences merely tolerate the new instead of embracing it. The audience learning rate thus becomes a barrier issue in adaptation and survival.

With regard to the latter point, the relationship between a single patron and an artist has a long history subject to much differing opinion. From an ecological perspective, the point of interest is that there seems to be a fundamental symbiotic relationship that is functional, based on real legitimate needs, and this relationship contributes to community collective interests and survival. In a sense, there is a micro-market for the two parties’ needs. For the patron, there is an outlet, both vicarious and real, for his or her own desires to contribute to culture and the arts through resource donations, payment for services, collection, critique, public presentation, and adulation/appreciation. For the artist, there are ego, aesthetic, financial, and social needs that can be nicely met by the patron arrangement. Society is served because the relationship may in fact serve an important “incubator function” whereby new ideas and innovations can be tried out in relatively safe environments (stable individual taste versus fickle public taste) until ready to be supported on their own merit by a larger audience. In modern times, it is not clear how well the function of these patron relationships is being cared for by public support programs. An important source of industry innovation and variation, perhaps important for long-run survival, may be dependent on this dyad relationship.

In a variation on an Orwellian theme: All orchestras are equal but some are more equal than others!

While each orchestra shares common general industry conditions and shares common organizational design, all symphonies do not share the same probability of decline or survival because their environments may be quite different. Some are more supportive than others because of very specific local and regional environmental differences. Since there is no direct industry competition, each symphony organization is free to draw support from within the limits of its local or regional urban environment. The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra draws its immediate audience support almost entirely from the Washington DC/ Maryland region, not from California or Florida.

Survival rates will depend largely on local conditions which are neither evenly distributed nor constant.

The munificence of an environment then depends on a combination of the “natural economic endowments” of location (the existence of plentiful or scarce resources, abundance or dearth of opportunity) with the “economic competitiveness” of that region (e.g., institutional arrangements, talent pool, strategy, leadership). Together these two variables create different rates of regional economic growth, and fluctuations of economic cycles in regional industries (e.g., oil in the Texas region, hi-tech in the Northeast, electronics and informatics in Silicon Valley, software and airplanes in Seattle).

Economic success and upbeat growth cycles in turn directly affect the availability of resources for cultural products. Since cultural products are often seen as luxuries, they are the first to “get cut” from budgets in times of economic downturns. A region that is experiencing growth and shares a sense that “times are good,” will more likely provide support for cultural institutions and their activities. Thus, while some symphonies have closed their doors in recent years, others (e.g., the Seattle Symphony and Los Angeles with the new Disney performing arts center) are getting new and often magnificent buildings. There may be no justice in this uneven spread of good environments, but then ecology is not about justice.

However, variations between environments themselves may give rise to variations of organizational form which, from the perspective of ecology, is a positive condition. Environmental differences help explain why failure is not necessarily an across-the-board phenomenon. A region that has fewer resources may still pursue the development of a local symphony organization. However, these organizations will necessarily differ in such important organizational features as size, talent, programming and repertoire possibilities, schedules, venue, and marketing effort. While they cannot reproduce the sound or tradition of the great orchestras for which much of the original music was written, they can mimic that art in a manner appropriate and fitting to the local environment’s needs. Mimicry has value as a survival strategy in nature.

One example of the workings of local variation may be the network relationships between major urban symphonies and surrounding satellite community orchestras. This is a variation of the center/periphery network problem, where the center tends to be the dominant player and the periphery plays a secondary role, “enjoying” the lagged effects of the outward flow of innovation, resources, and power. A case in point may be the New West Symphony located in the suburban valley region of Los Angeles. This new symphony takes advantage of its location to attract underutilized urban musical talent in innovative, market-driven programs which seem to promise a stable future.11

A second documented case, that of the Oakland Symphony, shows that environment alone does not determine survival. In that case, the combination of not understanding the changing environmental conditions, coupled with weak strategic analysis and choice, led to this failure.12 When its program was sufficiently differentiated from that of the San Francisco Symphony, the Oakland Symphony apparently thrived because the supporting public could differentiate between the programs and support of each, because different market tastes were being addressed. Once a change in the strategy lead to a “muddying up” of the distinctions, the audience could make immediate comparisons and chose programs of apparent higher value. If mimicry was the strategy, it did not work. Of course, the real story requires a much deeper explanation drawing on other factors such as the location of a venue in the center of a lower status city, the failure to develop a local audience, dependence on traditional conducting talent, problems in board selection, and the mishandling of a musicians’ strike. All of these actions exacerbated the situation which eventually lead to the failure of this symphony organization.

Where internal practices and the organization culture of the symphony organization lead to low differentiation, susceptibility to failure increases.

One way in which symphonies can vary and be uniquely differentiated is in the distinct sound that they produce. It has been argued that national culture differences produce differences in sound and style, making it possible to talk about a distinctly English or German orchestra. In addition, distinct sounds are produced through the long-term shaping of an orchestra under the baton of a single maestro. George Szell, after a lifetime with the Cleveland Orchestra, was able to create a singular sound and style, as if the orchestra was his instrument. Similarly, Eugene Ormandy created a certain silky sound for the strings and gave the musicians enough interpretive room to be expressive. Thus, they could excel at playing romantic music. Similar differentiations of sound and style can be identified for most of the great conductors. But central to these unique sounds was the long-term and constant residency of the conductor who had the time and interest to learn about the skills and nuances of players, and to shape the sound and style carefully over time. In a sense, the conductor put a signature on the music and essentially created a “brand.” From a strategic perspective, these orchestras acquired unique and inimitatable advantages. Since these specialized competencies could not be readily copied, the value of orchestra sound and style differentiation created market advantages, and the orchestra could realize the full market rents generated by its unique qualities.

Under contemporary conditions, the ability or the practice of developing a unique orchestral instrument seems diminished for a number of reasons. For one, the short-term and multiple simultaneous residencies of “conduct and run” maestros does not allow for such differentiation to be developed easily. In addition, differentiation in sound and style is diminishing because training is increasingly universal and standardized, producing an instrument that is more homogeneous and universal. With small differences in instrumentation between the orchestras, due to cost factors or repertoire choice, the ability to create a unique sound is further diminished. If the listening public does not know how to hear and appre- ciate distinct qualities, then its willingness to invest in multiple versions of works (in concert or recorded form) is greatly reduced. It will accept either a recorded copy of a “known older great” orchestra or it will be indifferent to quality differences and consume the standard fare. ( Naturally, this would occur less frequently, since mediocre performances provide less listening pleasure, and the marginal value of each new piece decreases overall enjoyment of the genre.) The result is to reward mediocrity in the long run as tastes diminish because of a downward cycle of negative feedback between audience and orchestra. This situation mirrors the competitive problems of the fine wine-sector of the wine industry. Teaching people how to appreciate and distinguish subtle differences in fine wines takes time and constant investment in messages and marketing strategies designed to get them to move “upscale” to the better product. Thus, we see that internal differentiation can contribute to long-term survival because of the advantages it creates in the marketplace.

In cultural organizations, the maintenance of tradition poses a particularly thorny and core strategic survival problem.

If all members carry on the same traditional culture fully and simultaneously, they expose themselves, en masse, to higher risks and rates of failure, if knowledge of and tastes for that cultural tradition weaken. Tradition can act as a conservative force that prevents or reduces variation and thus increases the probability of failure. In effect, this raises the issue of whether or not symphony orchestras are really “museums for museum music.”

If, on the other hand, symphony organizations eschew tradition in favor of individual survival strategies based on strong and high variation (e.g., very mixed programming and changes in ensemble configuration), then the distinct industry character becomes so differentiated and dissipated that its unique historical identity, thought to be important to its survival, disappears with the loss of a valued tradition. Critics and others have observed that even though mature sectors of the population tend to have more disposable income and/or time for cultural product consumption, they are also the ones most supportive of tradition and resistant to innovation in programming. Yet their economic support is needed to keep many symphonies alive as working organizations. If then the industry shrinks, certain advantages of large-scale and deep audience reach can be lost, further feeding a decline cycle.

Left to random choice of individual orchestras, then, it is not clear that what survives will constitute a valued core of important tradition. What continues as a cultural industry is then merely a random collection of survivors which constitute no unique cultural tradition or societal statement other than the fact that they survived market demands and other opposing forces.

Repertoire choice, however, depends on the approach and criteria used in judging a tradition. Is tradition a discrete phenomenon or is tradition a continuum? The whole struggle to keep one foot in the past and one in the future at the same time leads to some rather confused interpretations in the use of traditional culture for modern needs.

A case in point from the popular press is the use of “classical music” as a noxious stimulant to keep teenagers from hanging around stores. Apparently convenience stores have serendipitously discovered that playing classical music through outside speaker systems tends to disperse teenagers because they find the music unattractive, and perhaps even bothersome and irritating! Most likely, the music does not match their youthful energy and creates an internal “off beat” friction. Thus, they move on to new settings. In a second case, the governor of Georgia wants to propose, as part of the 1998 state budget, a project that provides classical music CDs to parents under the theory that “having that infant listen to soothing music helps those trillions of brain connections to develop.”13 In a final case, Penn Station in New York City broadcasts a continuous cycle of Baroque music in its newly fenced-off seating area for travelers. This serves to sedate stressed-out travelers. It also provides a consistent sound background against which travelers perhaps more clearly distinguish and pay attention to train arrivals and departures. But another purpose, as with the new fenced-off area, is to separate and protect travelers from unwanted contact with vagrants, mendicants, bored teens, and other folks who hang around train stations. The background classical music helps keep those separations and social distances. One can imagine Haydn’s reaction to hearing that his music is used to drive people away!

The “choice” question leads to a difficult policy challenge in a free society: How important is tradition for the survival of a society? And if tradition is important, what is the best way to preserve it? To the first question, we simply reflect on personal experience and a limited knowledge of history to argue that tradition is indeed important for the formation of identity and motivating a larger

sense of purpose and commitment to life and society. People with a solid sense of themselves as a people, reinforced by tradition, seem to be happier, healthier, and more likely to survive difficult times. It is interesting to note that tradition, and especially a tradition and skill in classical music, contributed much to the survival rates of Nazi death camp prisoners.

The conservation of tradition presents a very difficult societal problem which has no final solution. Ecology suggests that it is in the collective interests of the industry to support the variation that tradition often resists. Yet, in open markets with free competition, the limits of that differentiation cannot be known a priori

and centrifugal tendencies toward chaotic individualistic developments that threaten a tradition’s collective interests are real. Tradition, and its institutions, seems to serve as one of the centripetal forces to prevent such market-induced “chaos of taste and value,” yet tradition does not seem to have a “natural” mar- ket. Present markets are a mass phenomenon, fickle, subject to trends, quick to tire of a product, capable of being manipulated through advertising, and representing no deep judgment of connoisseurship. To a society’s leadership, the question is then raised: do you entrust your society’s cultural traditions to markets?

Markets may not be the most effective mechanism of choice to preserve traditions and the organizations that support them. They are, however, relatively efficient mechanisms for reflecting present choice in the allocation of resources through a price mechanism.

If the decision is left to open and free markets, present trends indicate that markets may fail to conserve tradition. Unless assiduously developed, the “classical music tradition” market will shrink in the face of competition from contemporary products and a new ethos in taste. In a sense, there is no long- term sustainable market for tradition per se.

In 1996, one music critic observed that “a tradition is treated as just another trend ready for replacement. . . . There is something amiss in these efforts to treat a tradition with no more seriousness than the latest passing fashion. . . . There is no direction or goal, no past to give context to the present.”14 These comments underline the crisis of tradition in symphonic music. In a consumerist, market-oriented society such as the United States, tradition has to be “sold” and get a continuing “vote” in the marketplace. But in order to do that, the tradition has to be made appealing to contemporary needs, thinking, tastes, and habits. But if it is to be made contemporarily appealing, it cannot remain a tradition.